The process of being democratic requires great courage. It requires constant practice. Duck ‘net practice’ for a day and your ability to be democratic will be diminished. And in the new India, there are many distractions that keep us away from this necessary practice.

From the time privatisation gathered pace in India, leading to a corporate culture, people from the corporate world have almost completely disappeared from democratic participation. There are very few exceptions. Scarcely anybody ventures out of his or her firm. It’s as if anybody who enters the corporate world is out of the democratic set-up, leading a lifestyle that prompts him or her to value democracy less and less. They start imagining India can only be saved by a dictatorship — naturally, a market-friendly dictatorship.

Although privatisation was presented as the answer to many of democracy’s ills, it has enfeebled the very idea of democracy. The corporate world has not provided a fillip to democratic participation because it has formed a nexus with the political class, and they are working together against the interests of the people. The political system enervates citizens at one end and the corporates keep citizens away from actively participating in democracy at the other end. Then together they can do as they please—acquire land here, raze a mountain there, create a situation where farmers are driven to digging holes and standing in them for weeks to demand a fair price for their land, but to no avail.

The more privatisation increases, the more democratic spaces shrink. Corporates have never had any interest in democracy. But we don’t examine the link between governments and corporations, we don’t question it. We don’t protest the electoral bonds scheme introduced by the government that will turn political donations completely opaque, making it easier for big business to capture the electoral process and impossible for the public to know how and to what extent government policies are tailored to benefit the big donors.

There is a lot that we don’t question, a lot that we just don’t see.

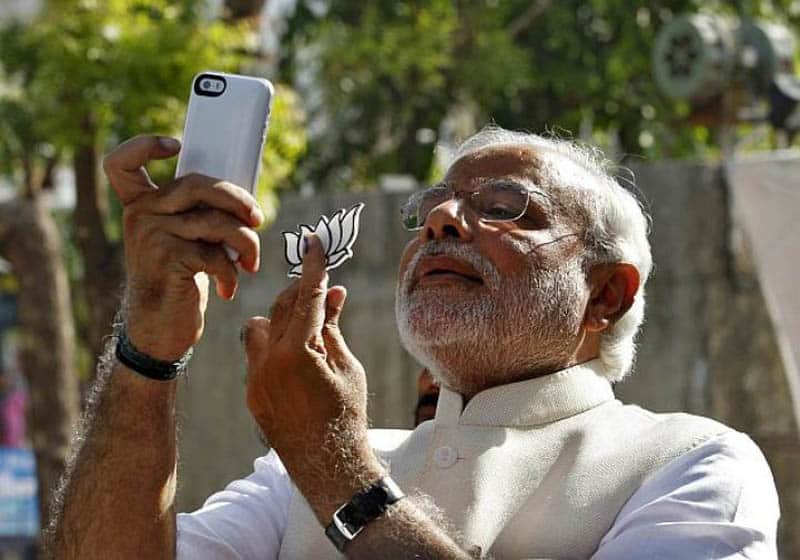

In December 2017, the winter session of the Lok Sabha, the country’s highest legislative body, was postponed because of the high-stakes Gujarat Assembly elections where Prime Minister (Narendra) Modi was scheduled to campaign extensively. The nation’s business was made subordinate to a state election. There was some debate about this in the papers, almost none on television. But how many of us really demanded an explanation? After all, in this age of social media it is possible to launch campaigns and make a lot of noise.

Even those of us who raised the issue of the Lok Sabha session being delayed did not notice a larger trend. For the last thirty years, the number of Vidhan Sabha sessions has dwindled alarmingly in state after state. Consequently, the significance of Assembly sessions in the running of a state government has reduced steadily. The Assembly is the platform where MLAs discuss issues relating to their constituencies and thus evolve into leaders. Today, if MLAs are not ministers, nobody knows them. They do their own thing, winning and losing elections, but are of little use to the people who elect them.

We have stopped looking at these institutions. We don’t bother to ask why a state’s chief minister or the prime minister chooses not to hold an Assembly or Lok Sabha session at the designated time or merely goes through the motions. Is it that we no longer have any confidence in the Vidhan Sabha or the Lok Sabha? I refuse to believe that. If we did not have confidence in these institutions, 70% or more among us would not be exercising our vote in election after election. I think the problem is that we have reduced our chief democratic right, and chief responsibility, to merely the act of pressing a button on the voting machine. Then we return from the polling station and submerge ourselves in the image of the leader who emerges victorious.

To have faith is a good thing, no doubt. But that faith should rest on the foundation of facts, not emotions.

In late 2017, the Pew Research Center, an American think-tank, released the results of a survey it had conducted in India during the first quarter of that year. The survey had been conducted among 2,464 people across India’s most populous states. (Yes, 2,464 persons. It is an intriguing figure, even forgetting that the country they were surveying is home to well over a billion people. Why not add another 36 people and make it 2,500, at least? Perhaps they had an astrologer advising them.)

The survey found that 88% of the respondents held a favourable opinion of Narendra Modi as prime minister—‘almost nine out of every ten’, said the survey. This in itself isn’t new or startling; some other surveys of the time had reported similar results. It is the replies to other questions that are cause for great concern.

To be honest, I was also worried for the tenth respondent in every batch of ten who did not find the prime minister the most popular leader. I felt like telling him, bhai, when nine respondents have gone one way, why are you standing alone on the other side? Then it struck me: this one man is the real democrat. By standing alone, away from the others, he was in fact doing a great service to Indian democracy. Otherwise, out of sheer anxiety that nine out of ten had gone over to one side, he could have decided to cross over, too, for a perfect ten! But he stood his ground. Whoever he is, I salute him. He has kept the prestige of democracy intact—standing apart and standing firm to ensure the leader had at least one opponent.

Predictably, the 88% popularity rating for the Supreme Leader among 2,464 people led to celebrations on Twitter. I wondered if the people who were in raptures had read the entire findings of the survey. Fifty-three per cent of the respondents favoured military rule in the country. Nine out of ten respondents put their faith in an individual who has come up through a democratic process; an individual who is by virtue of his political career a symbol of democratic aspirations, ascending from the position of chief minister to that of prime minister. Then why did five out of the nine who supported him favour military rule? Didn’t they have full faith in the elected leader they hailed as the most popular?

The respondents would have been asked one question: ‘Do you think military rule is good?’ Over half of them would have said yes. I would have asked them a second question: ‘Would you support a military rule where someone knocks on your door at two in the night and whisks you and your father away and locks you up in a dungeon for ten years without recourse to any lawyer or defence?’ Would the same respondents have answered yes to that question? I don’t think so.

And what name would they have given had they been asked who should lead that military regime? Would they have named a democratically elected leader? Would they have named the former army chief who is now a minister? That would have been logical, after all.

Just how muddled are we on the subject of democracy and the leader? Why are we so confused? Our confusion arises from the fact that the daily practice of democracy that happened in our institutions, be it in the media or any other institution, has become a thing of the past. Those daily ‘practice matches’ of analysis and interrogation are long gone. If we think the blame for this decline can be laid only at the door of the present government, we would be mistaken. It would mean we haven’t quite understood the age we are in. This deterioration has taken place over the last 25 to 30 years, as hyper-capitalism and its technologies have taken over our lives, as inequality has grown dramatically and demagogues have risen, and as institutions have been systematically dismantled or hollowed out. We may feel it more now only because the proportion of those who are alert to institutional erosion is greater today because it is happening at great speed.

The Pew survey also had 55% of the respondents saying they wanted a ‘strong leader’, one who could ‘make decisions without interference from parliament or the courts’. The survey report noted that ‘support for autocratic rule is higher in India than in any other nation surveyed.’

Why is a strong leader required? Is the framework of constitutional laws and powers given to a leader or chief minister so inadequate that a muscleman is needed in that position? Does the supreme leader have to wrestle with the cabinet secretary, administer some well-placed blows? Why this yearning for a strong leader, then? It would be understandable if the desire was for a leader who represents the strong will of the people. Perhaps it was. But do the kind of questions that are asked in these surveys allow for nuance? Do those who celebrate the results of such surveys have any time for nuance?

On the one hand there is a mythical narrative of a strong elected leader being created, and running parallel to it is a script for military rule. There might be a reason.

Until now our democratic institutions, even when functioning at their best, have roundly failed to fulfil the aspirations of the people. On the contrary, through these institutions, the control of vested interests on public resources and systems has become near complete. It is true not only of India but of countries the world over that one or two per cent of the population controls 90-95% of the nation’s wealth. This information has not emerged from some communist party office; it is based on surveys by economists who believe in the capitalist system. For instance, the figure of 1% or 2% controlling almost the entire wealth of some nations is from a report by OXFAM.

And this is what is making the political class nervous. Of the 90% or more of the population who are hard put to feed themselves, some are committing suicide for now. But the day they tire of taking their lives, they will rise in revolt. There are limits to dying, and there are limits to killing too. History is replete with the names of murderous tyrants; even so, in the end it was they who perished, not humanity.

This is the politician’s biggest anxiety. Whoever holds the reins of power is haunted by this fear. Tomorrow if some among us happen to be in power, the same fear will plague us. It is a legitimate fear, for politicians have nothing to show other than the same old formula of propaganda and event management. Democracy can be difficult to manage. This explains the dramatics of creating a halo around the idea of autocratic or military rule through strategic questions in regular surveys, because it is the easiest way to trample on the expectations and aspirations of the people, by co-opting them into the project of their own disenfranchisement. When we relinquish our standing as citizens, one day we will wake up to find a gunman standing outside our door and for the next 10 or 20 years we will lapse into silence, losing our power of speech and our language.

It is to this end that both the narratives of the strong leader and of military rule are being lovingly nurtured, even though both of them are among the most clichéd narratives, or formulae, of history. Those who have not delved into history will also grasp it. Those who have studied history will grasp it better. And even those who go around tearing posters will understand this formula if they stop to think.

If it is a strong leader we desire, how would we describe Gandhi, Mandela, Lincoln, Martin Luther King and Vinoba Bhave? Strong leaders, wouldn’t you say? The man with the frail frame who wore nothing but a dhoti and challenged the might of the British Empire—was he a weak or a strong leader? A strong leader does not necessarily have to be dressed to the hilt and thunder from a high stage; a half-naked, soft-spoken fakir can also be a strong leader. There shouldn’t be an iota of confusion in our minds about this. A half-naked fakir too can be a strong leader who, armed with a sense of purpose, set out with his lathi and in 30 years removed the fear of the Cellular Jail, Kaala Paani, embedded deep in the minds of the people, inspiring them to stand up to British might. It speaks of his courage and the strength of his conviction that a Bhagat Singh, a Chandrashekhar Azad and a Bose emerged from the same stream. That is why I say a strong leader does not always come in colourful bandis (jackets). A strong leader does not emerge when you fight over God one week and start building temples to Gandhi’s assassin, Godse, the next.

From 1940 to 1945, during the Second World War, the British prime minister, Winston Churchill, was incredibly popular—he continues to be quoted to this day—and people believed everything he said. He seemed to be the world’s biggest leader of the time; people were hanging on his every word in the belief that anything he said went a long way. He commanded blind faith. After the war, when elections were held, the same Churchill suffered a defeat at the hands of Clement Attlee. A strong leader also suffers defeat.

Living in a democracy, if we dilute our understanding of what it means to be the people, we will be betraying our freedom struggle. We give pensions to our freedom fighters, but how many of them do we know, those unnamed lovers of freedom who spent years in prison? Their children and their children’s children faced ruin across generations; relying solely on those meagre pensions they inexorably slid into penury. Those freedom fighters staked the futures of several generations of their families to win the right to be citizens of an independent nation. In honour of their memory, at least, we must not lose the essence of our great democracy and the right to be its people.

As for the narrative of the strong leader, it is a kind of time-pass, nothing more. He who takes everybody along is a leader, not one with a trail of people walking behind him. There were many tall leaders around Gandhi—Rajendra Prasad, Ambedkar, Nehru, Bose, Sardar Patel and many more. It is that which creates conditions for a true democracy. Where one leader dwarfs the landscape, there will be no lok, only tantra, no people, only a hollowed-out system, and the only thing left standing will be a temple of falsehood. We owe it to ourselves to rebuild our democratic consciousness and reclaim our right to be the people.

Courtesy: the wire

https://thewire.in/230898/where-one-bandi-wearing-leader-dwarfs-the-political-landscape-there-will-be-no-lok-only-tantra/