Will the U.S. protests bring Trump’s innings to a close, or will white America consolidate behind a “law and order” slogan? Will the protests change the way in which America’s police treats its blacks? Eventually, will these unexpected developments in the U.S. also encourage Indians to ensure justice for all?

Before offering such thoughts as I have on these intriguing and difficult questions, I want the Citizen’s readers to know that from mid-February I have been in the U.S., where I’ve taught for 23 years, while spending several months each year in India.

On June 4 I sent a piece, published on June 6 on another Indian portal, where, marking the size and ethnic diversity of America’s protests for equality, I added, “No one in the US seems able to recall anything like this happening ever before. It is a story of epic proportions.”

“Young Americans of all races have been streaming out,” I noted, “risking much, including the possibility of picking up the COVID-19 virus.”

Covid has played a role in America’s widening acknowledgment, surprising to many, of its racism. The ability of a 17-year-old bystander to capture on video the horror of George Floyd’s murder played another key role.

Locked in because of Covid, America’s millions saw that video again and again. Through that video, they also saw the ugly way in which their country was “enforcing its laws”.

One of those moments had arrived in America, rare in any country’s history, when its people say to themselves, “We were blind to what our brothers and sisters go through day after day.”

Whites began to repeat what for years blacks were asking them to recognize: “Black Lives Matter.” Blacks and whites jointly uttered that phrase as they marched on America’s streets. It was proclaimed from the roofs of buildings. White mayors in southern states with a history of backing the Ku Klux Klan voiced the three words, “Black Lives Matter.”

That historic admission seemed to bring a release to America’s whites, freeing them from the shame of abetting in racial injustice.

Covid had sharpened that shame because – before a nation’s TV-glued eyes — non-white Americans were dying disproportionately from the pandemic even as, hour by hour, other dark-skinned Americans were risking their lives, in hospitals and grocery stores and as delivery persons, to help fellow-Americans.

Trump’s numbers have taken a hit. His call for employing the army to suppress disorder in American cities was rejected by governors and mayors, condemned by former military leaders, and, even more importantly, questioned before TV cameras by his own defence secretary.

For a short while, Trump and his allies hoped that demands by black organizations for “defunding the police” would push deserting whites back to his camp, but that hasn’t happened, in part because those calling for “defunding” have made it clear that they want the police to continue protecting communities even as they want brutality to end.

I heard a white police officer who had previously served with the US army in Iraq declare on TV, “The police ought to see communities as neighbours, not as rebels.” This view accorded with the former military chiefs’ rejection of the thought of the U.S. army coming down on American citizens the way they would on enemy combatants.

Trump’s manifest mishandling of the pandemic has also, of course, hurt his appeal.

Politically, November lies far in the future. For now, however, Trump has cause for anxiety and Black America has grounds for hope, even though reconstructing the police will be a formidable task for any new administration. In a system like America’s, that task will confront mayors and governors more than the White House’s occupant, although the latter can influence America’s willingness to change.

It was a global ethno-nationalist current that strengthened men like Trump, Modi, Brazil’s Bolsonaro, Hungary’s Orban and Turkey’s Erdogan. It may be too early to conclude that what Trump now faces is also something like a global current, yet Covid, for one major thing, has not been confined to one or two corners of our world.

Influencing all lives, challenging every local, regional and national government, Covid has also given people everywhere the time, and the reason, to ask the frankest of questions. Including, “How fair and just is my country?” and “Are our leaders free from partiality?”

While organizing survival for ourselves and our loved ones, Indians and Americans have seen three powerful scenes: One, the extreme suffering of special classes of people. Two, the impartial bravery of every kind of person engaged in health care (Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, atheist or whatever in India; black, brown, yellow or white in the US). Three, the equal vulnerability to Covid of persons of every race, creed, caste and class.

There may or may not be a global political current today, yet there seems to be a kind of coming together, perhaps a fuller acceptance of our equality as human beings.

If this were not the case, would cities like London, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Madrid, and Melbourne have reverberated with the sounds of “George Floyd,” “Breonna Taylor” and “Ahmaud Arbery”?

Also interesting is the growing frankness about their own racialism in Indian American circles. In these circles, pro-Trump cries have suddenly died down. Indian Americans increasingly acknowledge the debt they owe to black leaders of the Civil Rights movement, which enabled some of the rights enjoyed today by U.S.-based non-whites.

Since Indians have often adopted trends in the U.S., will India also reproduce, at some point, the calls for justice now being voiced by much of white America? Who knows? Any global current is bound to run into national barriers.

Yet it might be an error to underestimate the yearning in Indians for equality and justice. Often suppressed by fear of consequences, or by a desire for the approval of domineering elements, this yearning came out most forcefully – we all remember — in the final months of 2019 and in January 2020. Across the nation, Indians of every persuasion openly protested against the exclusion of Muslims from the benefits of the Citizenship Amendment Act.

It may be reasonable to hold that the Indian sentiment for justice, a quiet but living force, has been reinforced by Covid’s message of an equal humanity and by America’s protests.

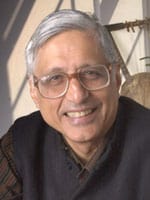

Rajmohan Gandhi is a biographer and a research professor at the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, US. He is the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi and Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari.