Jahan mein ahl-e-iman surat-e-khurshid jite hain/Idhar doobe udhar nikle, udhar doobe idhar nikle

The people of faith and courage live in the world like the sun/If they go down on one side, they rise up on the other side.

—Allama Iqbal

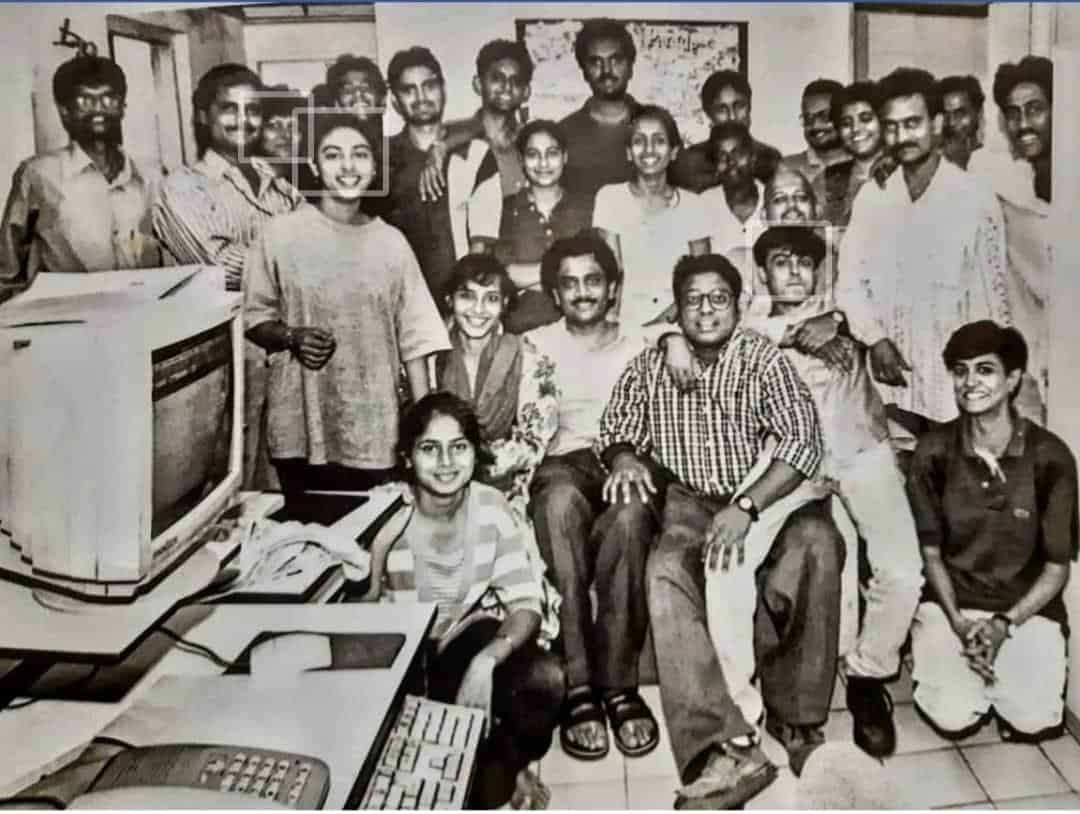

My good photographer friend Gajanan Dudhalkar has shared a photograph of The Asian Age’s editorial team taken at the newspaper’s Mumbai office then at Simon House, Sayani Road in Prabhadevi. The pic must have been shot sometime in 1997-1998.

Look at the B&W photograph carefully. At the far left is a tall, scrawny, bespectacled, buck-toothed boy standing near a PC. It is I. My kids are horrified that I looked so… well, they don’t use the word horrible or ugly out of respect but agree I appeared famished.

If a photograph is worth a thousand words, I must tell a tale bottled up inside me. The story seems to have found an utterance after Gajanan jogged memory with this rare picture from my life’s journey.

Having failed to find a foothold as a scriptwriter in the tempestuous Tinseltown, I enrolled for a Diploma in Journalism course at K C College, Church Gate in 1997-1998. A few months at the college, our teacher and veteran journalist Gangadhar Sir told me one evening:”Now is the time you should join a newspaper. You will learn more on the job than in my classroom.”

By saying this, the teacher who was also a senior columnist ignited a dormant desire in me to become a journalist. I soon realised how I had taken a wrong route when I tried to become a Salim-Javed at a time when major actors self-produced their films and Bollywood had got divided into camps. I spent two years there without getting any headway and it became clear I would die a struggler chasing as I was a chimerical goal. I don’t regret at not succeeding in the world of cinema.

Gangadhar Sir’s words still ringing in head, I headed to the College Principal G T Balani’s office with a request: a letter to Mr Aakar Patel, the then Resident Editor of The Asian Age in Mumbai, saying that I wanted to intern at the paper. With the Principal’s letter in hand, I called Aakar Patel from a PCO (mobile phone was a few years away) and excitedly introduced myself, telling him why I wanted to meet him. “Come tomorrow,” he said and snapped.

I spent the night tossing and turning in my bed, thinking of the questions the RE might ask. I had already updated my CV with a clear mission statement that I wanted to work in print media. I boarded a Church Gate slow train at Mahim and got down at Prabhadevi, a 15-minute ride. Located at Sayani Road in the middle class Maharashtrian pocket Prabhadevi, Simon House housed many corporate offices, including the Asian Age on the ground floor. Shiv Sena’s mouthpiece Samna too was in the neighborhood.

The receptionist at the Asian Age office, a girl in mid-20s, tried to test my patience by telling me ‘the editor is not in office, he will take time to reach’ blah, blah. I said I had an appointment and I would not go away without meeting him. After 15 minutes, she spoke to the RE on intercom and informed him about this new visitor. He immediately called me in. At first look I thought I had been ushered into a wrong room. A tall young man casually clad in jeans and T-shirt, his jet black hair parted, Aakar appeared more like a college boy than Resident Editor of a newspaper with multiple editions, including one from London. He took a break from writing on the computer to talk to me. The paper’s founder–editor-in-chief M J Akbar had an eye to spot young talents and promote them to responsible positions if they showed promise. And Aakar, son of a Gujarati businessman, had bucked the trend and not become another businessman but an editor at a young age. That he emerged as a good writer and columnist explains the faith he had in his then untapped abilities.

He glanced through my CV which had clippings from my previous writings at a small magazine in Nizamuddin West, Delhi. “Ok. Join from tomorrow,” he said. I left his cabin feeling vindicated. I had struck not a pot of gold but a pan of possibilities. Opportunities to think and write. Writing has therapeutic properties. It gives you a catharsis. It helps you take world’s burden off your chest. It fuels your mind and fixes the gaps in thought process. It elevates the mood and rejuvenates the mind. I looked forward to unlimited opportunities to experience all that.

A few months at reporting where I covered almost everything worth covering except business and sports–from lecture of Samuel P Huntington of Clash of Civilisations fame to gay lecture by Humsafar founder and LGBT rights activist Ashok Row Kavi, I joined the paper’s feature team. One day it was derailment of a local train and disruptions of suburban train services while the other day I would be sent to witness and report a show on how to protect your hair organised by the wives of IPS officers at a club in Worli. I seldom said no to an assignment as each assignment enriched me in its own way.

My batchmate from K C College, Mayabhushan Nagvekar, and I worked hard because we were trainees and had to prove our worth to the paper. On some Sundays–coincidentally today is Sunday when I am writing this, but locked in my home–Aakar, Mayabhushan and I, besides a desk hand, were in office and we brought out the paper. Under Akbar’s stewardship, the paper’s circulation had shot up. It pushed the boundaries in journalism.

Work was our worship. It got tested when the monsoon came. And, as you know, when it rains in Mumbai, it pours. That July it poured so heavily and lashed the city for so many hours that the railway tracks got flooded. The trains stopped. The trains were stopped and taxis got either stuck in knee-deep water or went off the road. The rains continued to lash the city even as day ended and night followed. We decided to stay back at the office. After eating our modest meal which came from a nearby restaurant, we held impromptu sessions of singing and Antakshri. Past midnight, the girls went to a room while the boys stayed at the Hall which was our newsroom. Putting our head on the long table, we pretended to be asleep for a few hours before day broke. The rains had stopped, the morning was bright but the trains had not started yet. My room was just a few kilometres away at Mahim. I walked to it. When I see desperate migrants walking home on the highways in hot sun and on burning road, I can feel their pangs and understand their precarious situation.

Since my confirmation letter took a few months to come, I survived by borrowing from friends. A pao-bhaji vendor would park his cartwheel across the road near the Simon House. Pao-bhaji became my staple for lunch. Soon I faced its side effects too. Constipation became so acute that my belly refused to take it anymore. When the pain became unbearable and my condition quite worrisome, Ganesh, a health reporter and colleague, took me to the casualty ward of the KEM Hospital in Parel, not very far from our office. The doctor said it was serious constipation, gave some tablets from the hospital pharmacy and prescribed a few others to be bought from outside. Ganesh gave me Rs 50 with which I bought the rest of the medicine. When my first salary came, I tried to return Ganesh his Rs 50. He refused.

(I owe you a big thank you, Ganesh. I have lost your contact. Please contact me if you get to read this.)

We were young and a bit adventurous too. Once a travel and tours company approached the features editor with an offer to send a reporter as part of a junket to Switzerland. I was the only male in our fabulous features team. The feature editor could have gone herself but she was kind and wanted another member to go on this junket. She checked with the girls if they had passport. The girls didn’t have or they didn’t want to go.

She checked with me. “Mohammed, do you have your passport,” she asked.

“Yes, I have it,” I replied.

“Would you like to go to Switzerland?,” she enquired.

“Yes, I will,” I said. I had not travelled by air till then. She asked me to contact the coordinator for travel details. In a week’s time I was airborne to the beautiful country, the land of snow-capped mountains and green meadows, Switzerland. It was my first ever flight, international or domestic. We travelled across peaks inside a cable car and played with snow. I remember MeenaI Baghel, then with The Indian Expres, too was there. I wrote, as many letters as others did. Even, a letter from a post office from one of the highest points in Europe, to my mother in Bihar. In that letter I said:”Daddy would worry that perhaps I would never sit in a car as a journalist. I flew and am in Switzerland.”

Her chest puffed with pride, mother showed that letter to all my relatives. I don’t know how my father reacted.

After nearly three years at the Age, it was time to move on. If Mr M J Akbar, the hero of my youth, is an institution in journalism, the Age was a good school. It nurtured many of us young, raw and rookie reporters into worth fighting the big battles ahead. It fanned the fire in the belly to take challenges head-on. It taught us to ask questions to the powerful.

Many of the traits were built and un-built in that room where this memorable photograph was clicked.

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog.