We learn that before 1955, India was the largest country in the world which permitted its great majority of people, Hindus and Muslims, to practice polygamy (unlimited to Hindus and limited to four wives to Muslims). In some parts of India, such as in Lahaul Valley of Himachal Pradesh and among the Thiyyas of South Malabar, polyandry prevails and was recognised under custom. Chota Todas as a community in Nagaland are said to have polyandry prevailing.

Paras Diwan, Customary Law, Chandigarh, 1991: “in several castes and sub-castes, divorce under customs has prevailed from the early Hindu period. Since customs derogatory to sacred law are allowed to prevail {Collector of Madhura vs Muto Ramlalinga [(1868) 12 MIA 397]}, customary divorces have been recognised. Customary modes of divorce are easy. In some cases marriage can be dissolved by mutual consent. Very little formalities for dissolving marriages are needed. In most cases, it is purely a private act of the parties. In some communities, some forum is required. It is either a gram panchayath, community panchayath or family council. One wonders: any problem if it is a local Qazi or the husband himself? Or if the husband delegates that power to his wife? Or is the problem something extraneous to the merit of the matter, tied up with mind-sets and prejudices, and only because the matter involves Muslims?

Such has been the importance of customary divorces in Hindu law that even after the reform and codification of Hindu law of Marriages, the customary divorces continue to be recognised (Sec. 29 (2) Hindu Marriage Act, 1955). Some Hindus have a system where a gram panchayath sits and issues a divorce declaration awarding also “compensation” to the woman and the divorce is complete. Compare this with the Islamic “and for divorced women, fair provision on a reasonable scale” (quoted in Shah Bano’s case). Are Hindus here inadvertently following Muslim personal Law?

Now, will all these diverse laws be abrogated? Or will we have a hybrid fabricated by engrafting or transplanting specific provisions of each on to the intended matrix of the total effort? What parts of which will be accepted by whom, subject to what safeguards? Has any exercise been carried out, or even attempted, to ascertain these basic aspects of what the diversities are and in which areas of law, look at possible variants that might find acceptability of any degree amongst at least relatively large parts of the religious spectrum of groups, denominations, sub-denominations, tribes, castes, etc.?

Even among the mainstream Hindus we have the two large schools, Dayabhaga and Mitakshara, which differ hugely in the inheritance provisions, the former being more like the Muslims’ law of inheritance in so far as the point at which a person acquires rights in property is concerned.

In later judgements the Supreme Court was pleased to voice another view. In Lily Thomas & others vs Union of India & others [2000 (6) SCC 224], the Supreme Court pointed out (headnote H and paragraphs nos. 41 through 44) that in another decision, namely, Pannalal Bansilal Pitti vs State of A.P. the Court indicated that enactment of a uniform law, though desirable, may be counterproductive, observing that in the counter-affidavit and supplementary affidavit on behalf of the Government of India in the case of Sarla Mudgal, President, Kalyani vs Union of India, (1995) 3 SCC 635 it is stated that the Government would take steps to make a uniform code only if the communities which desire such a Code approach the Government and take the initiative themselves in the matter. The Court pointed out the Government had also annexed a copy of speech of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar in the Constituent assembly on 2-12-1948. Dr Ambedkar stated, quoting from the Union of India’s affidavit, “I should also like to point out that all the State is claiming in this matter is the power to legislate. There is no obligation upon the State to do away with personal laws. … Therefore, no one need be apprehensive of the fact that if the State has the power, the State will immediately proceed to execute or enforce that power in a manner that may be found to be objectionable by the Muslims or by the Christians or by any other Community in India.” Now, if you do not do away with personal laws, then what are they for if not to be applied and implemented?

The Court reassuringly added that the affidavits and the statement made on behalf of the Union of India should clearly dispel notions harboured by the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Hind and the Muslim Personal Law Board. The Court added that the Court had not in Sarla Mudgal’s case issued any direction (emphasis supplied) for the enactment of a common civil code.

Then came Ashutosh Gupta vs State of Rajasthan & others 2002 (4) SCC 34 at para 6) where it was held (in the context of Article 14) that the concept of equality before law does not involve the idea of absolute equality among all, which may be a physical impossibility. All that Art. 14 guarantees is the similarity of treatment and not identical treatment.

Equality before the law means that among equals the law should be equal and should be equally administered and that likes should be treated alike. Equality before the law does not mean people with differences shall be treated as if they were the same.

In (2002) 7 SCC 368 at paras 31, 56, 84 and 97, Ms. Aruna Roy & others vs. Union of India & others, the Court said “religion is the foundation for value based survival of human beings in a civilised society. The force and sanction behind civilised society depends upon moral values.” The importance of religion in regulating human conduct stands recognised. Denuded of its constitutionally guaranteed practices, can religion remain religion? And who and with what intent are seeking to “do away with” religion-based laws?

In TMA Pai Foundation and others Vs. State of Karnataka & others (2002) 8 SCC 481 (eleven Judges) it was noted that regarding Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, the Human Rights Committee in its general comment adopted on 6-4-1994 stated the article establishes and recognises the right that is conferred on individuals belonging to minority groups and which is distinct from, and additional to, all the other rights which, as individuals in common with everyone else, they are already entitled to enjoy under the covenant. (Art.27, ICCPR : in those states in which ethnic religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of their group to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion or to use their own language.)

The Court explained that rights conferred on linguistic or religious minorities are not in the nature of privilege or concession, but their entitlement flows from the doctrine of equality which is the realde facto equality. Equality in law precludes discrimination of any kind, whereas equality in fact may involve the necessity of different treatment in order to attain a result that establishes equilibrium and parity.

International treaties have been held to be enforceable by law, and one can have the anomalous situation of a Constitutional Directive Principle of State Policy being not enforceable by any Court, and yet the very same provision be found to be enforceable in another garb, as a provision in a treaty signed or ratified by our country: an Indian Court could find itself unable to enforce a provision of the Indian Constitution, and yet able to do precisely what that directed, by decreeing enforcement of a treaty obligation.

Constitution, 5th Schedule, Item 5, says (1) notwithstanding anything in this Constitution the Governor may … direct that any particular Act of Parliament or Legislature of the State shall not apply to a Scheduled Area or any part thereof … or shall apply … subject to such exceptions and modifications as he may specify …

(3) In making any such regulations … the Governor may repeal or amend any Act of Parliament or of the Legislature of the State or any existing law which is for the time being applicable to the area in question (effective after Presidential assent).

Thus we learn from the Constitution that we can effectively have areas where even a “common” civil code does not apply even in parts of India. Diversity of laws, it seems, is very much a part of the Constitution!

Jai Hind.

Concluded

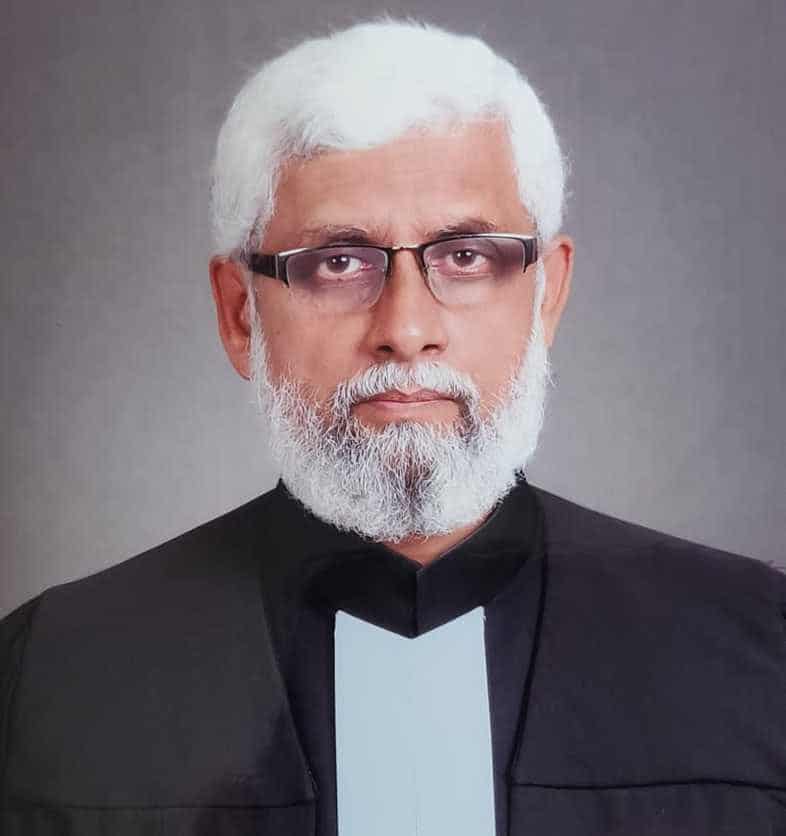

Shafeeq R. Mahajir is a well-known lawyer based in Hyderabad