By Syed Mohammed

It has been two days since Dada Hazrat passed. As I reflect on what he was and the kind of life he lived, I realise was a man who had few possessions but leaves behind a rich legacy.

You see, Dada believed in leading a simple life. Despite the resistance from my uncles, and irrespective of the fact that he came from a jagirdar family with vast tracts of land in Nandurbar, Maharashtra, for many years he travelled on his trusted Raleigh cycle. This was at a time when my father and uncles began to look at foreign shores for their sustenance.

It was always clear that he lived a simple life from the very beginning. He did not look down upon possessing wealth, but nevertheless shunned it himself. In a telling conversation of him espousing a frugal lifestyle, he told he told my father that the jagir was not for his personal use. I think that this means, he had little, or perhaps no interest, in keeping those land parcels in his possession.

But what he did possess was a wealth of knowledge and generosity which would last a lifetime. For many years, Dada Hazrat taught English and Social Studies to children studying in government schools and belonged to backward sections of society. He had this old, ‘black board’ which could be rolled up. It used to hang from a wall in his room. There was a cardboard box which stocked chalk in different colours. Around 4.30 in the evening students trickled in. And when there was a full house, it was a beautiful riot! They’d recite poems. They would read. They would write. They would chant lessons in unison.

I like to believe, and know for certain, that Dada Hazrat had little material wealth. And whatever he had – wealth from his pension, and knowledge – he gave away. He was always busy in the pursuit of knowledge and the transfer of knowledge. All this, collectively, is the hallmark of a true dervish.

But that is not all, Dada wore many hats. In a manner of speaking, he was an activist. And like all well informed activists, he would read. He read in the morning and he read at night. He liked to be aware of the important political and social developments. He used to write letters to magazines, local legislators, ministers and former Prime Ministers. An interesting incident, I am told, took place when I wasn’t even born. The year was 1960. It was time when Egyptian Premier and Arab Nationalist Gamal Abdel Nasser, (in)famous for a brutal crackdown on Hasan al Banna’s Muslim Brotherhood, in its former manifestation, was to arrive in India. Dada Hazrat was most displeased. Panditji, he said, should not have such a man in the country. Promptly he wrote a letter to the Centre, urging it to withdraw the welcome. Days after the letter was sent, a phalanx of policemen arrived at his doorstep. Was this bearded man with a prominent nose a threat to independent India’s national security? The family was worried. But, Dada Hazrat and Dadi Ammi were unfazed. Dada Hazrat was smiling, and Dadi Ammi stood by him like a rock.

It was a marriage of 50 years. Both loved each other deeply. But their disagreements were interesting to watch. Both were equals. In fact, I think Dadi Ammi had the upper hand, always. Dada Hazrat used to address Dadi Ammi as ‘Pasha’, a Turkish word to describe a high-ranking person. I have known and heard of men who have wanted to be buried near their mothers’ final resting place. But Dada Hazrat wanted to be buried beside his Pasha. On his right rests Dadi Ammi and on his left is buried his father-in-law Janab Syed Zainul Abideen, Hyderabad Civil Services, and then collector of Raichur District.

Dada Hazrat knew that roots of patriarchy run deep. He was a firm believer that men and women are equals. It is only deeds which make them better than the other. So, Dada Hazrat knew he had to take the bull by its horns. He knew he had to talk to us about it. After all, we were dozens of first cousins. These ‘fellows’ should not turn into ruffians. He also knew that a man’s ego, no matter how young or old this man is, is fragile.

I remember one such incident. My wife resigned a couple of years ago. A couple of days Dada Hazrat got wind of it. He called her to his room and gently asked her, “Is it because of that ladka (yours truly) that you have quit? Call him here and I will talk to him. An educated woman should not sit at home.”

Dada Hazrat always wanted his tribe to grow. The fact that after nearly seven years of marriage my wife and I had no children caused him great concern. It was cold evening. I hadn’t seen him in a couple of days so I decided to pay him a visit. No sooner than I uttered ‘assalaamualaikum Dada’, he held my hand in an iron grip. He pulled me closer to him. The ensuing conversation caught me off guard, and at the same time had me guffawing.

“Mohammed Miyan! Did you get yourself tested?”

“Kaiku Dada? Kya test?”

“Fertility test!”

In his booming voice he said, and I quote him verbatim, “It is no laughing matter, my boy! Usually, it is the man who is infertile and the woman is blamed.”

These women’s empowerment-esque traits were clear from the very beginning. All of my aunts are educated, working women. In fact, some of them are more qualified than their respective husbands. Most of them are professionals.

Dada Hazrat was the first to tell me that love for one’s mother is paramount. He would always sing songs which encouraged a son or daughter to whatever he or she could for the mother.

“Behisht maa ke qadam neeche

Hadeeson mey bhi paaya hai

Behisht maa ke qadam neeche”

This means, Paradise lies at the feet of one’s mother. It is a Prophetic tradition.

We knew Dada Hazrat disliked to talk about differences within the Muslim community. The Muslim community (and the world) isn’t a monolith. Every jamaat or jamiat or tanzeem has done some good work. Appreciate this, learn and move on. Confrontation is usually useless and destructive.

So, if one were to mischievously ask, “What do you think of Muawiyah?” he would say, “Yeh sawaal aapki qabar mey nahi poochha jayega.” Nevertheless, we knew his opinion well.

I remember him saying the Urdu equivalent of ‘just-stick-to-the-basics-and-the-rest-will-follow’. The imaarat can be strong only if the foundation is strong.

‘ا’ سے اللّٰہ کو پہچان

‘ب’ سے بڑھوں کا کہنا مان

‘ت’ سے توبہ کر انسان

‘ث’ سے ثابت رکھ ایمان

For those who cannot read Urdu, here is the transliteration:

Alif se Allah ko pehchan

Bey se badhon ka kehna maan

Tey se tauba kar insaan

Sey se saabit rakh imaan

And as my millennial cousins say, “Keep it simple, bro.”

But Dada Hazrat wasn’t without his complexities. Before Independence, he gravitated towards Maulana Maududi’s Jamaat-e-Islami. But post-Independence, he began to disagree with its ideology. In order to keep the flame of dawah alive, he joined the inward-looking Tableeghi Jamaat. In fact, he was one of the four or five people who first embarked on a jamaat from Hyderabad.

But despite this, Dada Hazrat choose to keep things short and simple. My cousins and uncle would take him for Jumma namaaz. As soon as the imam ended prayers, he’d say: “Assalaamualaikum! Ek minute ki baat suniye.” He would then speak for a minute or less about the importance of prayer, azkaar, education, being professional and respecting women. Initially, (the few times I went to namaz with him) I’d feel embarrassed. But some people used to come to him after dua and thank him for the naseehat. He would then take their hands in his and give them dua.

Day and night, Dada Hazrat was the embodiment of the Islamic direction of غور و فکر, or contemplation. He would read like there was no tomorrow. He would read the Qur’an, The Bible, Ramayana, tafaaseer, books of history, magazines, newspapers and whatnot.

And as a part of his غور و فکر exercise, he marvelled at Allah’s creation. Nothing fascinated him more than the stars. Of course, he knew like all others what stars actually are. But there was some romanticism here. He would sing about the stars, and what a lovely voice he had.

اللہ میاں کے تارے

بکھرے ہے آسماں پر

یا یہ چراغ لاکھوں

جلتے ہیں آسماں پر

اما مجھے یہ تار

لگتے بہت پیارے

جی چاہتا ہے میں بھی

بن جاؤں ایک تارا

ہو روشنی سے ماری

روشن جہاں سارا

Simple and folksy, here’s the translation:

Allah Miyan ke taare

Bikhre hain aasmaa par

Ya yeh charaagh laakhon

Jalte hai aasmaa par

Amma mujhe yeh taare

Lagte hai bohot pyaare

Ji chaahta hai main bhi

Ban jaaoon ek taara

Ho roshni se meri

Roshan jahaan saara

But age was catching up with him. But Dada tried to outrun it. His roshni was fading, but his spirit of ghour-o-fikr, contemplation, would not let him go down without a fight. He would lie flat on his bed with a table lamp close to his left shoulder. If he was losing his right eye some seven years ago, he would cover it with a black lens fixed in his glasses, keep books on his chest and read.

Eventually, he lost his eyesight. But that did not dampen his spirits. A lot of people would, I assume, curse their fate, or blame God after they lose their eyesight. I would probably try to kill myself. But not all people are Dada Hazrat. But I never heard him complain about anything. He just smiled. So, he saw us with his hands. He used to feel our faces to identify us. For instance, he would touch my chin, glide his hands up to my cheeks, and judging by the length of my beard, he’d say, “Kaun? Mohammed miya?” He would then take my hand and place it against his chest and smile. The Urdu word for what I felt is sukoon. There was some sort of serenity I felt when he did that. As if all the stress had faded. It is something I will crave to feel till the day I die.

Again:

Allah Miyan ke taare

Bikhre hain aasmaa par

Ya yeh charaagh laakhon

Jalte hai aasmaa par

Amma mujhe yeh taare

Lagte hai bohot pyaare

Ji chaahta hai main bhi

Ban jaaoon ek taara

Ho roshni se meri

Roshan jahaan saara

As you can see, there’s humble ambition. But more importantly, there’s that quest for spiritual illuminance. And that was what Dada Hazrat was for most of us. A brightly shining, guiding star. I will wait for the remainder of my life in the hope to clasp his hands in mine when we meet again.

Inna lillahi wa inna ilaihi rajioon.

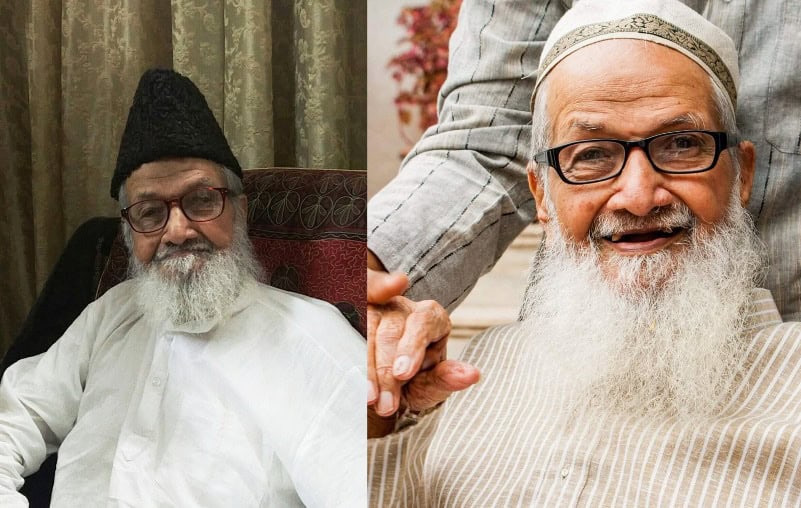

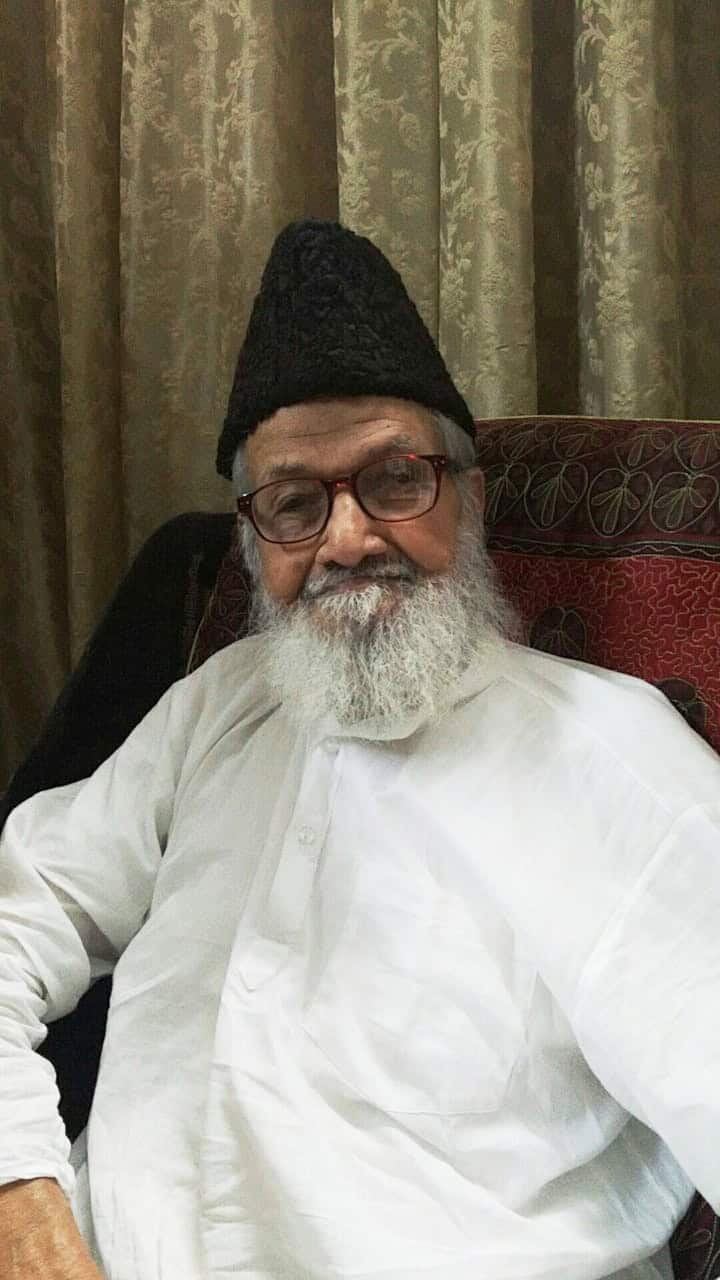

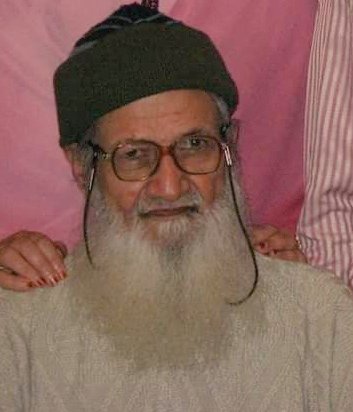

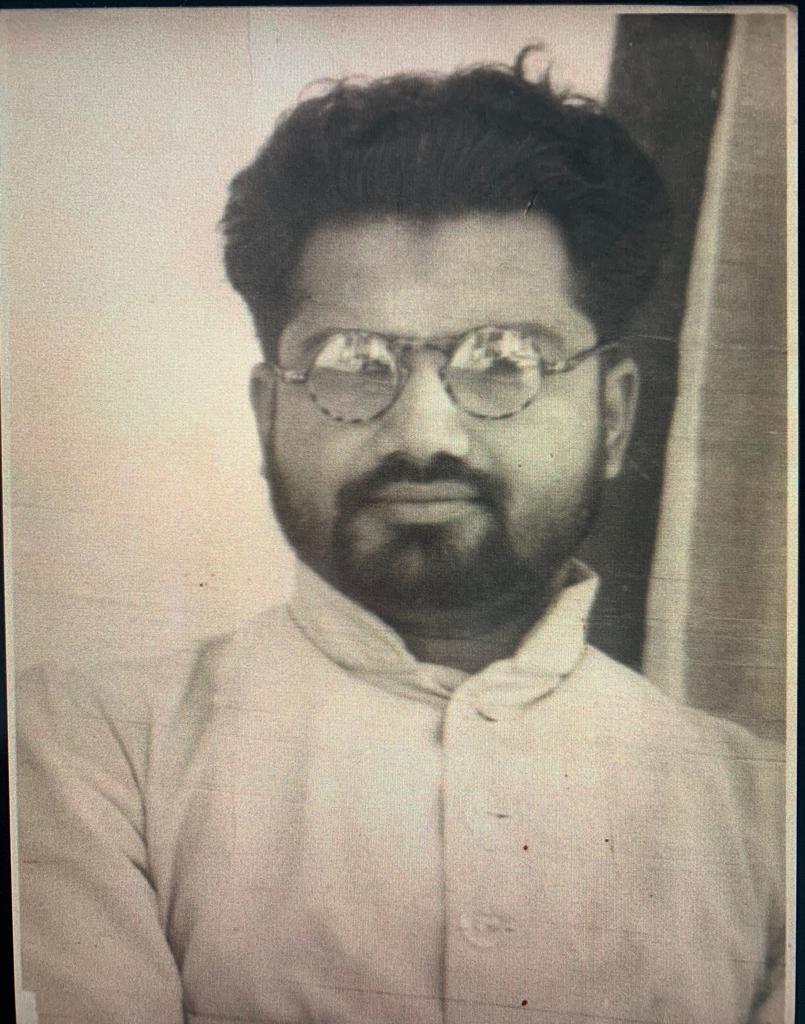

It may be mentioned that Janab Syed Hidayatullah Peer Zada Al Maroof Abdul Fatah Peer Zada, ex-employee of AG Office, Hyderabad had passed away at the age of 95 years. He had died in NIMs Hospital.

It may be noted that he was the resident of Turub Bazar. Initially, he was involved in Jamat-e-Islami and then he took active part in Tableeq Jamat. He was one of the founder members of Tableeq-e-Jamat in Hyderabad.