New Delhi: India is a rare example of the successful management of diversity in the developing world but the events of the past few years make it necessary to “reaffirm the patriotic idea of India enshrined in our Constitution” to build a “New India that will cherish and uplift” all its citizens, noted author and parliamentarian Shashi Tharoor writes in a scholarly new book that methodically takes the reader through the world of patriotism, citizenship and belonging.

“The healthy spirit of acceptance of difference, of constitutional encouragement of debate and discussion, fuelled by a thriving free media, contentious civil society forums, energetic human rights groups, assorted autonomous institutions, and the repeated spectacle of our remarkable general elections, are all assets for India’s civic nationalism.

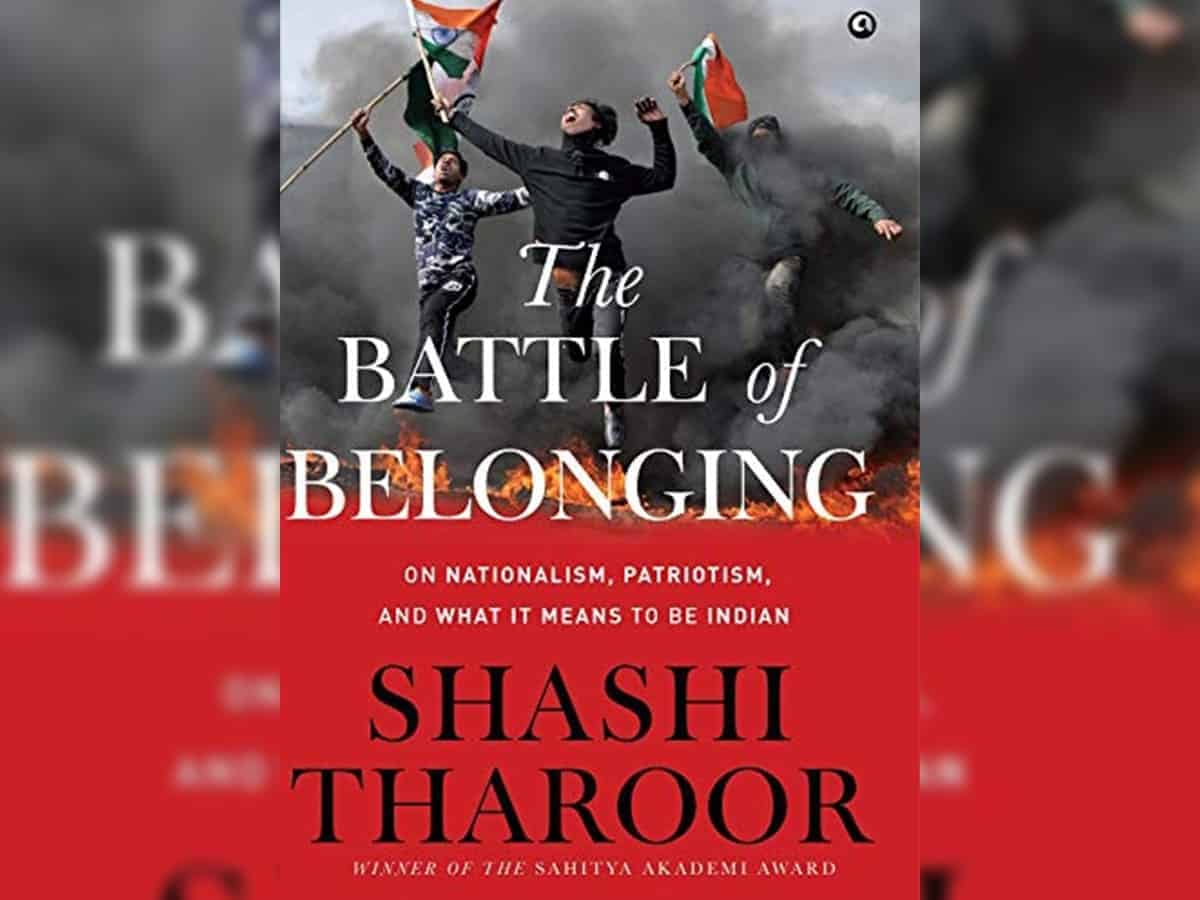

“Together with a fractious and competitive political culture, sustained by the proactive framework of the Constitution, they have made of India a rare example of the successful management of diversity in the developing world,” Tharoor writes in “The Battle of Belonging – On Nationalism, Patriotism, And What It Means To Be An Indian” (Aleph).

“It is time to reaffirm the patriotic ‘idea of India’ enshrined by our Constitution, in order to build a New India that will cherish and uplift each and every one of us. This requires a conscious effort to defend the besieged institutions of civil nationalism, restore their autonomy and ensure their effectiveness,” he writes.

Towards this, “we will need to separate the powers and roles of the legislature, the judiciary and the executive to ensure that the first two do not become mere rubber stamps for the third”, Tharoor states, harkening back to his book “India Shastra” in which he had advocated a Presidential form of government “with a clear separation powers, in order to ensure efficiency and democracy”.

Elected chief executives at all levels, from village heads up to the President, would “have the mandate, the authority and the resources to deliver solutions in their respective areas, to be accountable to independent elected legislatures, and an autonomous judiciary, and to face voters at the end of fixed terms”, he writes.

The existence of such multiple power centres “would ensure decentralisation and prevent the emergence of a hyper-nationalist strongman, while celebrating patriotism and the best features of civic nationalism at all levels”, Tharoor maintains, even as he admits he is “conscious of how little support there is in India’s political class for a presidential system”.

Even so, Indianness is constantly being remade “in a continuous process of deliberation and democratic discourse, a process that must continue (and that civic nationalism permits and encourages) in perpetuity”, he asserts, adding: “To defend and strengthen our civic nationalism , with its unique overlay of everything that is good and valuable about India, we will also need to undertake a careful retelling of modern Indian history that is comprehensive, embraces all experiences, and refuses to see the past through the prism of any one faith.”

Recalling that Swami Vivekananda spoke of the religion professed by the majority in this country, Hinduism, as “one that does not merely tolerate other faiths but accepts them as they are”, Tharoor writes that this acceptance of difference has been “the key to our country’s survival, making….’unity in diversity’ the most hallowed of independent India’s self-defining slogans. It is that unity we seek, not uniformity; it is consensus we must pursue, not conformity”.

Noting that this requires a “rearmed liberalism, with a mass movement for the restoration of our civic nationalism” the author writes that the “battle of belonging in our country is a battle between two ideas — the idea of a civic nationhood of pluralism and institutions that protect our diversity and individual freedoms, pitted against the ethno-religious nationalism of the Hindu rashtra”.

To effectively wage this battle, Indian liberalism “needs new ideas, precepts, narratives and heroes. It must be rooted in genuine patriotism and refuse to cede ground to the Hindutva bakths on nationalism”.

“It also needs a wide social coalition as Gandhiji was able to build for his nationalism” and probably also needs to “move out of the Khan Market circles so beloved of the Lutyens elite, to the mohallas, the jhuggi-jhopris, the rural hamlets, and the streets of India”.

It will also have to be ensured that the South is not “provoked into political disgruntlement by Hindu chauvinism, financial inequity or centralised government. We must once again help Muslims and other minorities enjoy the assurance that they are integral parts of the Indian nationalist narrative. Only by maintaining civic nationalism, and its commitment, through liberal constitutionalism, to a democratic and pluralistic ethos, can new India be able to fulfil the aspirations of all Indians”, Tharoor contends.

If India is to “reclaim its soul”, he writes, “the urgent national challenge is to restore, empower, and renew the very institutions of civil nationalism that the BJP has commandeered and weakened. These are the institutions that can best protect the minorities and the marginalised, that protect free speech and the expression of unfashionable opinions, that elevate principles and values above the interests of politicians in power, that offer shelter and aid to the vulnerable, and so create the habits and conventions that make democracy the safest of political systems for ordinary people to live under”.

Such an India “can not only survive but thrive, if we reassert and rebuild the civic nationalism in which our Constitutions embeds it. We must remain faithful to our founding values of the twentieth century if we are to conquer the looming challenges of the twenty-first”, Tharoor concludes, but after a caveat: “Only then will we be able to look a questioner in the eye and say with upright stance and uplifted gaze: ‘This is my nation. I am proud to say that I am an Indian’.”