New Delhi: When speculation was rife about an imminent takeover of the ailing Air India by a Tata Sons SPV, a wit had commented: “For the Tatas, Tata doesn’t mean goodbye.”

Truly, the carrier that Jehangir (J.R.D.) Tata launched as Tata Airlines on October 15, 1932, which rose to become one of the leading airlines of the world named Air India International, was nationalised in 1953, and then got reduced to an ailing behemoth by successive governments after 1977, is finally back home, a year shy of its 90th anniversary.

Young Jehangir was bitten by the flying bug in his childhood, thanks to Louis Bleriot, the French aviator who was the first to fly across the English Channel in 1909. The pioneering pilot knew Jehangir’s father, R.D. Tata, well, and their children too became good friends. And whenever Jehangir would spend his summer holidays at a beach resort in northern France where his father’s friend had a home, he would see Bleriot’s chief pilot occasionally land a plane on the beach. He even took a joy ride on one of these flights.

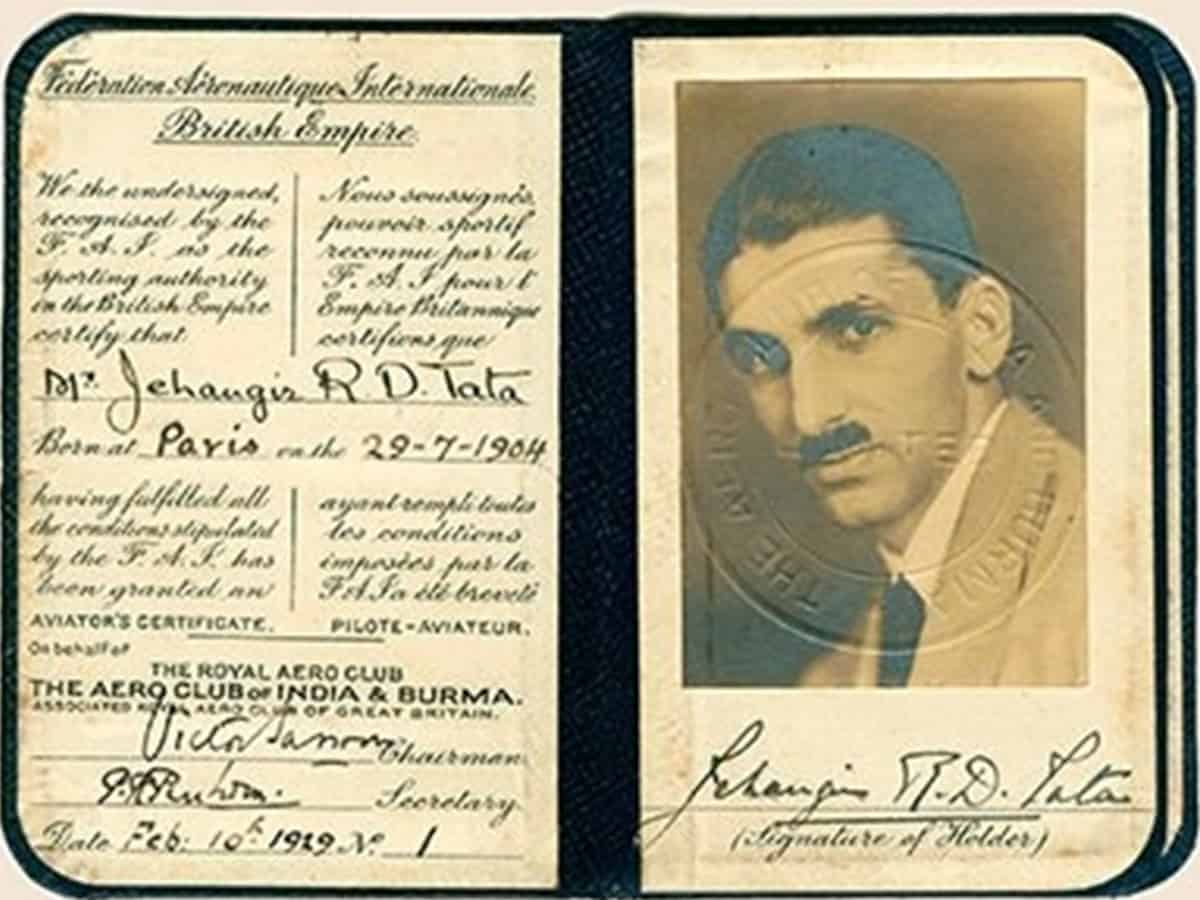

These experiences fired Jehangir’s imagination, but he had to wait till he was 24, when a flying club opened in Bombay and could give him an aviator’s licence — he was the first Indian to get one in India — on February 10, 1929. In the following year, the Aga Khan announced a cash prize of 500 pounds sterling for an Indian who would fly solo between England and India.

Jehangir completed the flight between Karachi and London, but not before another pilot, Aspy Engineer, flew into Karachi from London. Engineer won the prize, was recruited to the Royal Indian Air Force, and went on to become independent India’s second Chief of Air Staff, succeeding Air Chief Marshal Subroto Mukherjee.

The prize may have eluded Jehangir, but he made history on October 15, 1932, when, flying from Karachi at a ‘dazzling’ 100 miles an hour, he landed in Bombay via Ahmedabad in a wood-and-fabric, second-hand two-seater de Havilland Puss Moth loaded with air mail. The Karachi-Bombay route was important because the Imperial Airways flight from London terminated in Karachi. There was clearly a business opportunity here, for the mail from the imperial metropolis had to reach the Jewel in the Crown.

The final destination of the flight was Madras via Bellary. It was completed by Neville Vintcent, a former Royal Air Force pilot who had convinced the then Chairman of Tata Sons, Sir Dorabji Tata, who was quite reluctant at first, to invest the Rs 200,000 that Jehangir required to set up the airline. Vintcent became the first chief pilot and manager of Tata Airlines, which had two other licensed pilots — Jehangir Tata and Homi Bharucha.

Recalling those days, J.R.D. Tata said: “We had no aids whatsoever on the ground or in the air, no radio, no navigational or landing guides of any kind. In fact, we did not even have an aerodrome in Bombay. We used a mud flat at Juhu, which was then a fishing village-cum-beach resort near the city. The sea was below what we called our airfield, and during the monsoon the runway was below the sea! So, we had to pack up each year, lock, stock and barrel — two planes, three pilots and three mechanics — and transfer ourselves to Poona, where we were allowed to use a maidan as an aerodrome, appropriately under the shadow of the Yerwada Jail!” The jail, incidentally, was where the British Raj had imprisoned Mahatma Gandhi in 1932-33.

Despite working in such primitive conditions, within a year, Jehangir was able to establish Tata Airlines as the quality benchmark of the country’s fledgling aviation sector. The annual report of the Directorate of Civil Aviation (DCA) for 1933-34 stated: “As an example of how an airmail service should be run, we commend the efficiency of Tata Services — even during the most difficult monsoon months when rainstorms increased the perils of the Western Ghat portion of the route, no mail from Madras or Bombay missed the connection at Karachi, nor was the mail delivered late on a single occasion at Madras.”

Jehangir launched Air India International in 1948, at a time when flying was considered a luxury meant only for the rich. To raise capital for his aviation company, as the scholar N. Benjamin points out, he wrote letters to the rulers of Bikaner, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Jamnagar, Jammu and Kashmir, Travancore and other, and also sent them share application forms.

Their response was positive and soon, civil aviation took wing in the country under the stewardship of J.R.D. Tata. Even Jawaharlal Nehru, who was not a great fan of private enterprise, wrote to Tata: “I have had plenty of information from various sources, both official and non-official, about the running of your air service to Europe. All accounts agree in speaking well of it and praising it for its general efficiency. Congratulations!”

It is this legacy, nurtured in challenging circumstances, that has come back to where it rightfully belongs. Tata Sons will now have to carry the dual burden of carrying forward the legacy and measuring up to the expectations of the nation.