Moses Tulasi

“In my Government’s view, Hyderabad is not competent to bring any question before the Security Council; that it is not a State; that it is not independent; that never in all it’s history did it have the status of independence,” said Sir Ramaswamy Mudaliar responding to the appeal made by Hyderabad against India’s military action on Thursday, September 16th, 1948, questioning whether Hyderabad could even approach the UN on its own.

Mr. Mudaliar, one can assume, being the official representative of India, was aware of the clause under the Indian Independence Act of 1947. In this historical piece of legislation, the British specified that they “could not and will not in any circumstances” transfer the paramountcy they held over Princely States to the Indian Government.

This meant Hyderabad was legally an independent entity after August 15th, 1947. What could then be the reason Mr. Mudaliar was leading the UN on a red herring? What followed could perhaps answer that. Mr. Mudaliar asked for time until the following Monday to produce documents to prove his claim that never came about. Hyderabad surrendered the very next day. He was just buying time for the ‘invasion’, which had already started on the September 13th, to complete.

The first complaint from Hyderabad was received at the United Nations via a cablegram on August 21st that brought to their attention the “grave dispute which has arisen between India and Hyderabad, and which, unless settled in accordance with international law and justice, is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security.

Hyderabad has been exposed in recent months to violent intimidation, threats of invasion and to crippling economic blockade* which were intended to coerce it into a renunciation of its independence.”

Reaching out to the UN was a last resort on the part of Hyderabad after all negotiations with India had invariably failed.

Before the UN could sort out its priorities, Hyderabad followed up with a desperate appeal on September 12th notifying them of India’s official proclamation to invade Hyderabad and asking for the earliest possible hearing. The next day, the 13th, another cablegram from Hyderabad notified the UN that it had been invaded. Despite this, the earliest the UN could prioritise the case was on the 16th.

The Hyderabad delegation led by Moin Nawaz Jung, the then Finance and External Affairs Minister had it’s own share of problems to reach Paris where the UN had been meeting. This is because India had banned all flights from Hyderabad to fly in its airspace since July 1948 and point blank refused to make an exception — even for the delegation.

Laiq Ali, the then Sadr-e-Azam (Prime Minister), shares in his memoir that “alternate” arrangements had to be made for sending the delegation to Paris. Going by his confession that there was a “further delay” in the delegation’s travel plans because of Jinnah’s death on September 11th, it could be deduced the delegation was smuggled into Pakistan by the likes of Sydney Cotton, from where they would have flown to Paris. Cotton was an Australian gun-running pilot already chartering in essential items, arms and ammunition.

At the next meeting of the UN on September 20th, the Council observed a telegram the Agent General in Hyderabad, K M Munshi had purportedly sent on behalf of the Nizam instructing the delegation to withdraw the case from before the Council.

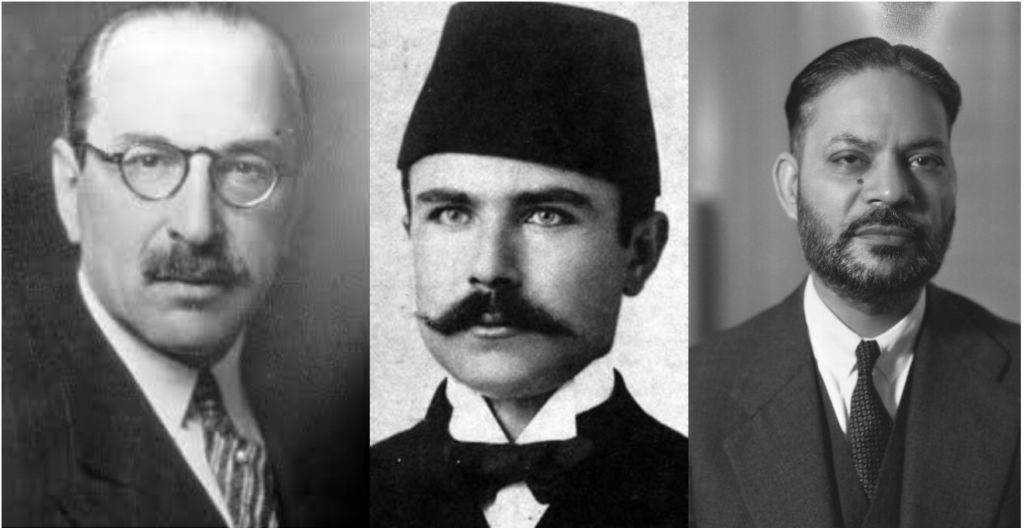

At this, the delegate of the United States, Philip Jessup commented, “The use of force does not alter legal rights.” The delegate from Argentina, Jose Arce expressed his surprise “only two or three days ago the Indian representative promised us all the necessary information to enable us to decide upon the competence of the Council…He has furnished none of the arguments he promised.”

The representative from Columbia, Umana Bernal, wondered what attitude the Council would adopt in the future should the state of Hyderabad disappear completely. The delegate of Canada however expressed that “the situation in Hyderabad has improved” and he was “reassured by the statement made by India”.

The Council met again on the 28th and started the session with a communication from the Nizam himself this time. This pertained to the resignation of his ministry on the 17th — on whose behalf the Hyderabad delegation was at the UNO.

Hence, he suggested, the current delegation be rendered null and void.

The representative of Syria, Fares El-Khouri raised suspicion on the authenticity of the message suggesting an independent investigation. Jose Arce added “the Security Council must request the Govt of India to withdraw its troops from Hyderabad and re-establish the former Govt there.”

The UN president, Sir Alexander Cadogen doubted the communiqué “whether it was written under some kind of compulsion”. Moin Nawaz Jung confirmed that the Nizam was completely under the control of the Indian Military. At this, Mr. Mudaliar quoted a speech of the Nizam from the 23rd in which the Nizam disavowed his delegation and asserted he was acting on his own free will.

He charged the Council of ‘gangsterism’ and suggested it “would be the wisest thing for the Council to drop the matter and allow peace in my country including Hyderabad” before the Council concluded.

The next series of meetings of the Council saw the delegate of Pakistan, Sir Zafrullah Khan and the delegate of Syria, El-Khouri constantly bringing up the matter of Hyderabad only to be turned down due to the unavailability of a representative from India. This made El-Khouri flare up “the failure of Indian delegation to have adequate representation surely does not mean that all meetings should be postponed.”

The matter had to wait till May 1949 to be taken up again where Sir Zafarullah Khan brought the Council up to speed on what had been alleged to be an intervention to maintain order, had instead become a conquest and absorption. He expanded on the woes of the Hyderabad ministers and other leaders. These were the people who resisted the Indian attack and were put on trial without proper counsel. Many such officials were replaced and their property confiscated. The Council resounded with absolute silence.

On that day after Mr. Khan put the issue to be and since then not a word had been spoken ever again.

Clyde Eagleton, an advisor to the Hyderabad delegation observed about the case at the UN – “In all other cases, the Council had tried, and frequently achieved a solution; in this case it did not even try. There is not in the records of the United Nations a more complete failure, and the failure is entirely it’s own.”

*of essential items such as rice, salt, petroleum, chlorine etc.

– Based on a white paper published by Clyde Eagleton in the American Journal of International Law, v 44.

Moses Tulasi is a filmmaker and a video journalist who has earlier contributed to FirstPost, Telangana Today and Rediff.