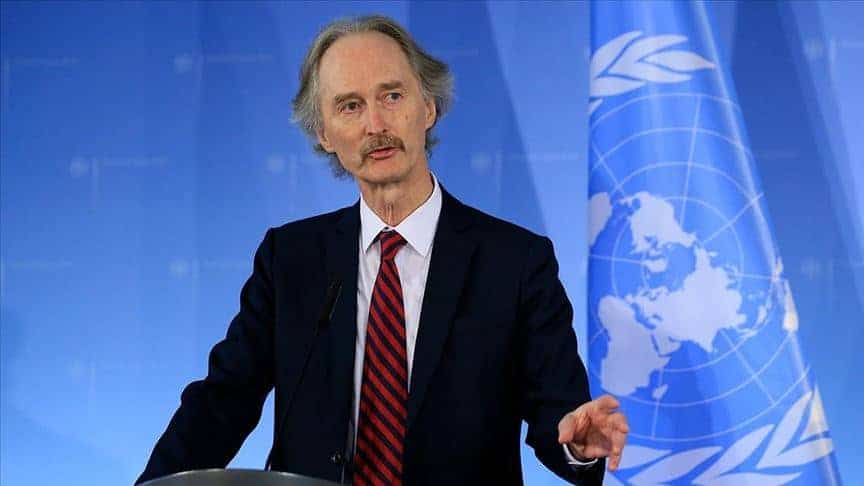

The 45-member “small group” of the Syrian Constitutional Committee, made up of government, opposition and civil society representatives, met in Geneva under UN auspices last week to discuss the “basic principles” of the new Syrian constitution. Afterwards, all that UN special envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen would say was that some potential “commonalities” had emerged, confirming that discussions had a long way to go.

On the sidelines of these talks, the members of the Astana peace process — Russia, Iran and Turkey — called for the sovereignty of Syria to be respected, a rebuke to the US for backing the separatist Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the northeast of the country. At a special session of the UN Security Council on Friday, the Syrian permanent representative condemned the “terrorism, aggression, foreign occupation and unilateral coercive measures” of the US and the EU in his country.

These diplomatic initiatives have been overshadowed by widespread fighting in Syria. Throughout January, every war front was ablaze and every faction was in conflict with others. These deadly confrontations are a sharp reminder to new US President Joe Biden that the 10-year old Syrian war remains vibrant, and there will be no quick resolution of the competing interests of the main players.

Turkey challenged the SDF in a new area in the northeast: Ain Issa. This town is 45 km from the Turkish border and, hence, outside Turkey’s “safe zone.” Ain Issa’s importance is that it is located on the M4 highway and is also the headquarters of the local Kurdish administration. Turkey’s plan is to disrupt Kurdish authority and affirm its own control over the highway. Turkish shelling is said to have led to several thousand residents fleeing to Raqqa, about 55 km to the south.

In another northeastern province, Hasakah, the SDF has been fighting government forces in order to dilute the regime’s presence in Kurdish territories. This standoff forced the Russians, who have been promoting a government-Kurdish rapprochement, to maintain peace in the region by deploying their own forces.

Syria also faces threats from a wide variety of extremist forces and splinter groups with diverse agendas. The rejuvenation of Daesh cadres in eastern Syria has been confirmed by a spate of kidnappings for ransom and killings in the countryside around Deir Ezzor. The Daesh-linked Amaq News Agency has claimed that, in 2020, it mounted 600 attacks, in which more than 1,300 people were killed. While most attacks were in the Deir Ezzor area, others took place in Raqqa, Aleppo, Homs, Hasakah and Dara’a.

Several other extremist outfits are located in the Idlib warzone. While Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham is in control of the town and is quietly working with Turkey, some militants, who are not comfortable with this affiliation, have set up their own units that have been carrying out attacks on Turkish and Russian targets. Thus, Hurras Al-Din attacked the Russian Tal Al-Saman base north of Raqqa in early January. Describing the Russians as the “aggressive enemy,” the outfit thus signaled its uncompromising ideological approach, its fighting capacity, and its disenchantment with the Turkish-Russian truce arrangements at Idlib.

Other more shadowy organizations have hit Turkish targets, though there is some uncertainty as to whether they have links with Al-Qaeda, Daesh or even the ruling regime in Damascus. Turkey, for its part, has consolidated its military presence to the south and east of Idlib with 20,000 well-armed troops in anticipation of major efforts by the government, backed by Iranian-supported militants, to retake the town.

Not unexpectedly, Israel has been the most active protagonist in this lethal theater. On January 13, it launched its fourth strike on Iranian facilities in the Deir Ezzor province in the east. These strikes hit several targets — the Imam Ali military base, Iran’s largest base in the east, and ammunition dumps — and killed 57 personnel belonging to the Quds Force and its allied militias from Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

These Iranian facilities had recently been moved away from areas near the Israeli border toward the Iraqi border. After the Israeli attacks, the Iranians moved their personnel and equipment to residential sites in Deir Ezzor, Al-Bukamal and Al-Mayadin, with rockets and heavy weapons being kept in tunnels. Another set of attacks was launched by Israel on January 22 near Hama, the first attacks after Biden’s inauguration. With these moves, Israel signaled that all Iranian targets in Syria are within its sights.

But the principal message is directed at Biden: Concerned about the potential revival of the nuclear agreement with Iran and the attendant lifting of sanctions, Israel has deliberately heightened tensions in Syria to encourage the US president to be more circumspect in re-engaging with Tehran. It is making it clear that it finds Iran’s presence in Syria as abhorrent as the nuclear agreement, while its generals are using sharp rhetoric to indicate Israel taking unilateral military action to safeguard its interests.

With so many players in Syria’s enduring dance of death, the scenario in that beleaguered country will only get murkier.

Talmiz Ahmad is an author and former Indian ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE. He holds the Ram Sathe Chair for International Studies, Symbiosis International University, Pune, India.