In July 2010, the CBI arrested Amit Shah in connection with the allegedly staged killing in 2005 of Sohrabuddin Sheikh. In September 2012, the Supreme Court shifted the case out of Gujarat, to Maharashtra, stating that it was “convinced that in order to preserve the integrity of the trial, it is necessary to shift it outside the state.” Shah was discharged by the special CBI court in Mumbai in December 2014.

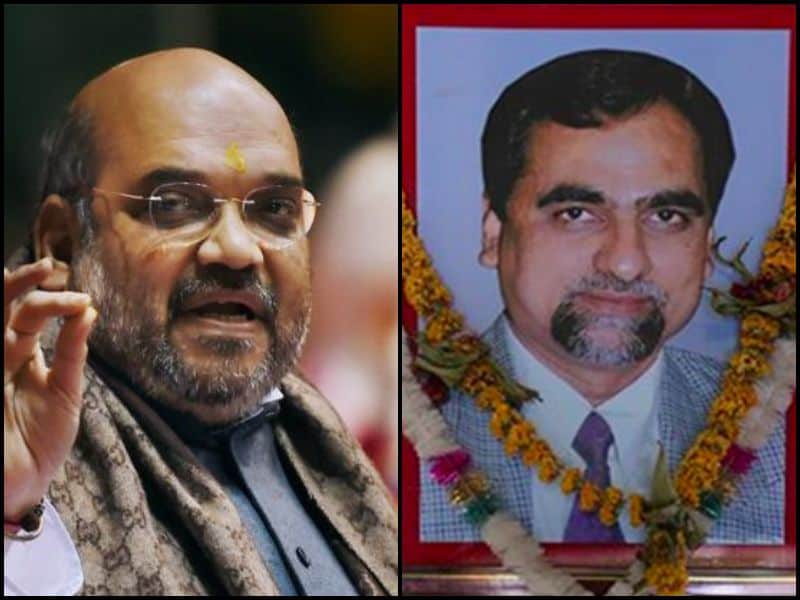

Brijgopal Harkishan Loya, the judge presiding over the CBI special court in Mumbai, died sometime between the night of 30 November and the early morning of 1 December 2014, while on a trip to Nagpur. At the time of his death, he was hearing the Sohrabuddin case, in which the prime accused was the Bharatiya Janata Party president Amit Shah. The media reported at the time that Loya had died of a heart attack. But my investigations between November 2016 and November 2017 raised disturbing questions about the circumstances surrounding Loya’s death—including questions regarding the condition of his body when it was handed over to his family.

Among those I spoke to was one of Loya’s sisters, Anuradha Biyani, a medical doctor based in Dhule, Maharashtra. Biyani made an explosive claim to me: Loya, she said, confided to her that Mohit Shah, then the chief justice of the Bombay High Court, had offered him a bribe of Rs 100 crore in return for a favourable judgment. She said Loya had told her this some weeks before he died, when the family gathered for Diwali at their ancestral home in Gategaon. Loya’s father Harkishan also told me that his son had told him he had offers to deliver a favourable judgment in exchange for money and a house in Mumbai.

Brijgopal Harkishan Loya was appointed to the special CBI court in June 2014, after his predecessor, JT Utpat, was transferred within weeks of reprimanding Amit Shah for seeking an exemption from appearing in court. According to a February 2015 report in Outlook, “During the CBI court’s hearings that Utpat presided over for this one year, or even after, court records suggest Amit Shah had never turned up even once—including on the final day of discharge. Shah’s counsel apparently made oral submissions for exempting him from personal appearance on grounds ranging from him being ‘a diabetic and hence unable to move’ to the more blase: ‘he is busy in Delhi.’”

The Outlook report continued: “On June 6, 2014, Utpat had made his displeasure known to Shah’s counsel and, while allowing exemption for that day, ordered Shah’s presence on June 20. But he didn’t show up again. According to media reports, Utpat told Shah’s counsel, ‘Every time you are seeking exemption without giving any reason.’” Utpat, the story noted, “fixed the next hearing for June 26. But on 25th, he was transferred to Pune.” This was in violation of a September 2012 Supreme Court order, that the Sohrabuddin trial “should be conducted from beginning to end by the same officer.”

Loya had at first appeared well disposed towards Shah’s request that he be exempted from personally appearing in court. As Outlook noted, “Utpat’s successor Loya was indulgent, waiving Shah’s personal appearance on each date.” But this apparent indulgence may just have been a matter of procedure. According to the Outlook story, “significantly, one of his last notings stated that Shah was being exempted from personal appearance ‘till the framing of charges.’ Loya had clearly not harboured the thought of dropping charges against Shah even when he appeared to be gentle on him.” According to the lawyer Mihir Desai, who represented Sohrabuddin’s brother Rubabuddin—the complainant in the case—Loya was keen on scrutinising the entire chargesheet, which ran to more than 10,000 pages, and on examining the evidence and witnesses carefully. “The case was sensitive and important, and it was going to create and decide the reputation of Mr Loya as a judge,” Desai said. “But the pressure was certainly mounting.”

Nupur Balaprasad Biyani, a niece of Loya’s who stayed with his family in Mumbai while studying in the city, told me about the extent of the pressure she witnessed her uncle facing. “When he was coming from the court, he was like, ‘bahut tension hai,’” she said. “Stress. It’s a very big case. How to deal with it. Everyone is involved with it.” Nupur said it was a question of “political values.”

Desai told me, “The courtroom always used to be extremely tense. The defence lawyers used to insist on discharging Amit Shah of all the charges, while we were demanding for the transcripts of the calls, submitted as evidence by the CBI, to be provided in English.” He pointed out that neither Loya nor the complainant understood Gujarati, the language on the tapes.

But the defence lawyers, Desai said, repeatedly brushed aside the demands for transcripts in English, and insisted that Shah’s discharge petition be heard. Desai added that his junior lawyers often noticed unknown, suspicious-looking people inside the courtroom, whispering and staring at the complainant’s lawyers in an intimidating manner.

Desai recounted that during a hearing on 31 October, Loya asked why Shah was absent. His lawyers pointed out that he had been exempted from appearance by Loya himself. Loya remarked that the exemption applied only when Shah was not in the state. That day, he said, Shah was in Mumbai to attend the swearing-in of the new BJP-led government in Maharashtra, and was only 1.5 kilometres away from the court. He instructed Shah’s counsel to ensure his appearance when he was in the state, and set the next hearing for 15 December.

Anuradha Biyani told me that Loya confided in her that Mohit Shah, who served as the chief justice of the Bombay High Court between June 2010 and September 2015, offered Loya a bribe of Rs 100 crore for a favourable judgment. According to her, Mohit Shah “would call him late at night to meet in civil dress and pressure him to issue the judgment as soon as possible and to ensure that it is a positive judgment.” According to Biyani, “My brother was offered a bribe of 100 crore in return for a favourable judgment. Mohit Shah, the chief justice, made the offer himself.”

She added that Mohit Shah told her brother that if “the judgment is delivered before 30 December, it won’t be under focus at all because at the same time, there was going to be another explosive story which would ensure that people would not take notice of this.”

Loya’s father Harkishan also told me that his son had confided in him about bribe offers. “Yes, he was offered money,” Harkishan said. “Do you want a house in Mumbai, how much land do you want, how much money do you want, he used to tell us this. This was an offer.” But, he added, his son refused to succumb to the offers. “He told me I am going to turn in my resignation or get a transfer,” Harkishan said. “I will move to my village and do farming.”

I contacted Mohit Shah and Amit Shah for their responses to the family’s claims. At the time this story was published, they had not responded. The story will be updated if and when they reply.

After Loya’s death, MB Gosavi was appointed to the Sohrabuddin case. Gosavi began hearing the case on 15 December 2014. “He heard the defence lawyers argue for three days to discharge Amit Shah of all the charges, while the CBI, the prosecuting agency, argued for 15 minutes,” Mihir Desai said. “He concluded the hearing on 17 December and reserved his order.”

On 30 December, around one month after Loya’s death, Gosavi upheld the defence’s argument that the CBI had political motives for implicating the accused. With that, he discharged Amit Shah.

The same day, news of MS Dhoni’s retirement from test cricket dominated television screens across the country. As Biyani recounted, “There was just a ticker at the bottom which said, ‘Amit Shah not guilty. Amit Shah not guilty.’”

Mohit Shah visited the grieving family only around two and half months after Loya’s death. From Loya’s family, I obtained a copy of a letter that they said Anuj, Loya’s son, wrote to his family on the day of the then chief justice’s visit. It is dated 18 February 2015—80 days after Loya’s death. Anuj wrote, “I fear that these politicians can harm any person from my family and I am also not powerful enough to fight with them.” He also wrote, referring to Mohit Shah, “I asked him to set up an enquiry commission for dad’s death. I fear that to stop us from doing anything against them, they can harm anyone of our family members. There is threat to our lives.”

Anuj wrote twice in the letter that “if anything happens to me or my family, chief justice Mohit Shah and others involved in the conspiracy will be responsible.”

When I met him in November 2016, Loya’s father Harkishan said, “I am 85 and I am not scared of death now. I want justice too, but I am extremely scared for the life of my daughters and grandchildren.” He had tears in his eyes as he spoke, and his gaze went often to the garlanded photograph of Loya hanging on the wall of the ancestral home.

Courtesy: The Caravan