By A. Suneetha

The apprehensions and tension regarding “secularism” of the Telangana movement reached its zenith during the election to Mahboobnagar assembly constituency in March 2012 (Mohd. Ismail Khan, Two Circles.net, 21 March).

The Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS), in a strategic move, fielded a Muslim candidate Syed Ibrahim against its main opponent, BJP, which fielded a dominant caste candidate, Srinivas Reddy. The campaign was viciously communalized by the BJP where it called the TRS candidate Syed Ibrahim and the 40,000 strong Muslim voters of the constituency razakars and anti-national. Contrary to the expectations of the TRS, Mahboobnagar was the only constituency in which they lost with a narrow margin of 1800 votes among the 7 assembly constituencies. This loss was interpreted by Muslim formations such as Muslim Forum for Telangana and others as a deliberate one that resulted from lack of support and campaigning for Syed Ibrahim.

Mohammed Ibrahim

Srinivas Reddy

Does it enable us to conclude that the Telangana movement was particularly non-secular, or that it relied on the mobilization of the Hindus, or that the trends in the last few years were entirely due to the aggressive expansion of the Hindu formations, including the BJP?

Perhaps it is not easy to do so, as, at each point, the non-party Telangana formations and the movement carefully responded to the criticism. After the Nizam controversy, attempts have been made to incorporate the positive elements of his legacy. Siddipet was visited by members of the political Joint Action Committee and others. After the Mahboobnagar fiasco, the Telangana political Joint Action Committee made sure that adequate support and campaigning was done for the TRS candidate from backward class in the Parkal by-election to ensure his win. More importantly, forums such as Deccan Archaeological and Cultural Research Institute, Singidi Telangana Writers Association, Telangana Charcha Vedika and Hyderabad Book Trust have sought to revisit the event of “Integration of Hyderabad state” into the Indian union to even raise issues of propriety and legitimacy of this action by the just-formed Indian state. But, despite the responsiveness of the Telangana movement, the epithet “Razakarsas” is in the air, to be used whenever needed, against the Muslims.

Telugu identity, history and the Muslim past

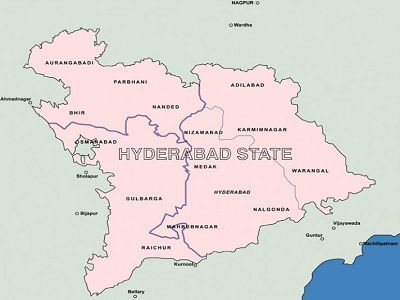

In fact, we need to go to the founding moment of the state of Andhra Pradesh in 1956 to understand the predicament of Telangana Muslims. Nine districts from the erstwhile Hyderabad State, now split into Kannada, Marathi and Telugu speaking areas were merged with the Telugu speaking areas of Madras Presidency that were already functioning as the first linguistic state since 1953. After obtaining the unwilling Osman Ali Khan’s acceptance to its sovereignty, the Indian Union had managed to crush the Telangana Armed Struggle of 1948 and the Communist Party’s turn towards ‘Vishalandhra’ after its withdrawal of the armed struggle helped the process of the amalgamation of two different regions into a larger linguistic state.

Even as new histories of the region are being written (Datla 2013, Bhukhya, 2009, Venkat, 2011), messing up the neat story of the Telugu nationalism “casting off the yoke of the British colonial dominance and later, that of the Asaf Jahis and of its founding moment ‘as an amalgam of the sacrifice by Poti Sriramulu and the communist struggle against the last Nizam – the figure that haunts the Telugu Muslims is of that of the Razakar.

Razakar was a private volunteer force that the pre-1948 Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen under Qasim Razvi — who has been memorialized as the chief villain in the story, especially in the historiography of the Telangana region and its integration with the Andhra state — raised to defend the “freedom” of the Hyderabad state against the mighty Indian state. Though the force was active for less than two years, it has lived on in popular memory, appearing in all the incidents outlined above.

In contrast, what has remained unacknowledged and undocumented in the political history of the state, despite the recent efforts to re-visit the history of the period, are the effects of the episode called Police Action or Operation Polo on the Muslims of the region. This period saw massive killings of ordinary Muslims, destruction of their properties and subsequent dispossession from homes and jobs, especially (but not confined to) in five districts of Marathwada and three districts in Karnataka. This episode remains shrouded in silence (Jairath and Kidwai; M.A.Moid, 2010, Swaminathan Aiyer, 2012,), officially and unofficially, with Sunderlal Report remaining buried.

Most Hyderabadi Muslims prefer not to speak about it while the Telugu speaking Muslims have had no opportunity to do so till now. The official four-volume history of Hyderabad State, commissioned by the then Congress government after 1956 (Rameshan, 1966) has no mention of these events. P.Sundariah’s history of the Communist Party’s role in the Telangana Armed Struggle, compiled in 1972, while mentioning the atrocities committed by the Indian army on common people and the party cadre between 1948 and 1950 has no mention of atrocities committed on Muslims by the army or the mobs that accompanied them. Inukonda Thirumali’s history from below, Against the Dora and the Nizam, published in the 1990s, that contested communist historiography also has no mention of the fate of Muslims “peasants or landlords” after the fall of Hyderabad.

Scores of personal memoirs written in the 1950s, prominent being K.M.Munshi (1998) and Ali Yawar Jung (1949) or later by a few communist leaders also do not mention any of these. The most recent in such popular-political histories was brought out by the Andhra Pradesh Congress Party (Rama Rao) in 2008 “where the distinctions between the nationalists, Communists, Arya Samajis, Congressites, social reformers, language enthusiasts get erased in the struggle against Nizam.” Most of the memorializing, popular and political, of this period highlights what counts or what is important to the nationalist-secular history of this period “of the autocratic” nature of Nizam, of the feudal oppression of peasants by the landed aristocracy, of the atrocities of Razakars on peasants. Muslim interest and political agency get categorized into pro/anti-nationalist or pro/anti-communist or pro/anti royalists but fail to explore their anxieties as an emerging minority in the region’s politics.

In the post-liberalization school textbooks introduced during the Chandrababu Naidu’s regime, even the Hinduised regional history (Chekuri, 2011) of Telugus does not figure in the school syllabus (Deepa et.al 2006) whereby even a mention of Qutb Shahi and Asaf Jahi dynasties has been deleted depleting the limited space that Muslims may have in the region’s memory. With adequate demonization of All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen and the Muslims associated with it, politically active Muslims from outside Hyderabad have to tread a careful path vis-a-vis the mainstream political parties and the administration.

The vernacular Muslim literary movement that emerged in the 1990s, called Muslimvaadam (Muslim ideology) has begun to powerfully articulate this lack of space for specifically Muslim concerns in the Telugu public sphere, problematizing mainstream Telugu culture’s indifference to Muslims, their lives, history and culture, and aligning with the dalit-bahujan politics and concerns. In a series of writings [Fatwa (1998) Aza (2002), Watan (2004), Mulki (2005), Jakhmi Awaz (2012)] poetry, fiction, non-fictional writings on Muslim identity, reservations etc., they announced the arrival of the Telugu Muslims as a political voice. And it is they who are asking why the low caste Muslims who suffered during Operation Polo should bear the burden of ‘integration’ even today. Khaja, a prominent poet of this movement points to the strange predicament that this popular memory has put Muslims like him in: On one hand, a Muslim like him gets labelled as an inheritor of razakars and on the other, he remains suspect and un-owned by political formations in the contemporary period. Is it because owning him also means owning his complex history and bigotry that he has been subjected to?

Why should the overriding narrative of the formation of Andhra Pradesh be the memory of Razakars and the valiant fight against them by a combination of communists, nationalists and others?

What have been the effects of this narrative on the lives and voices of Muslims in Telangana and other regions? What kind of historical narrative allows us to override the memory of razakars to make way to speak about the lives of ordinary Muslims like him? What is the meaning of secular-national identity for Telugu Muslims when their history, losses and suffering remain unnamed and un-nameable? When their very entry into the Telugu identity has been through this rite of passage, can they inhabit this space and dream about the promises that it makes?

What can be said at this point is this that while the concerns of the Telangana movement are developmental and secular, and its cultural articulation of regional backwardness intensely rich, its receptivity to Muslim political aspirations and concerns still remain caught in the larger ideology of Telugu nationalism and linguistic identity, which had cleared it of the taint of Muslimness.

(Concluded—First part of this article was published in siasat.com on Tuesday, September 17, 2019)

Dr. A. Suneetha is a Senior Fellow at Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies, Hyderabad.