Mohammed Wajihuddin

When I hear complaints of desperately poor not getting enough relief and some people refusing to give ration to a group of needy because they belong to a particular religion during the coronavirus-induced lockdown, I am reminded of how an Indian employee of the British government had honestly and justly handled relief works during a severe crisis.

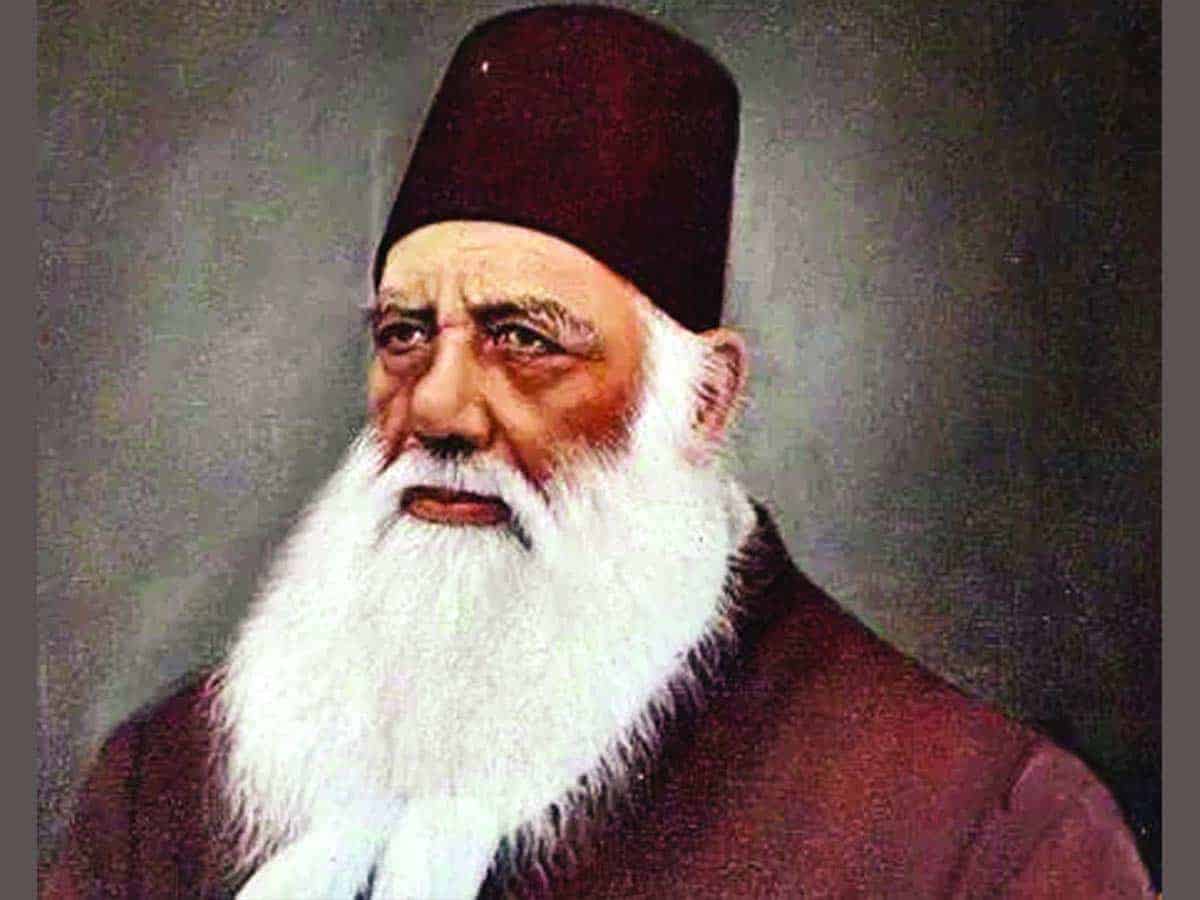

But before we come to the relief organised by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817-1898) after a severe famine broke out in 1860 in Moradbad where he was posted as Sadr us Sudur (Judicial Magistrate), let us look at another tragic episode of his life.

In 1855 Sir Syed was promoted from first class Munsif and transferred to Bijnor as Sadr Amin. When the revolt of 1857 broke out Sir Syed was in Bijnor and saved 20 Europeans at the risk of his own life. He guarded their houses day and night and dispatched them safely to Roorkee before he left for Meerut, the epicentre of the revolt. A chronicler has said that he reached Meerut in tattered clothes and six paisas in his pocket. In lieu of saving the European families, the British government wanted to reward him with a taluqa ( a big estate) which had an annual revenue collection of Rs one lakh then. Sir Syed felt hurt and refused the offer.

He was in Meerut when he heard of the great suffering his family in Delhi had faced. He left for Delhi and, on reaching, found that his uncles and cousins had been killed. He found his mother in utter ruin living at a stable with a maid named Zaibun. The stable was closed from inside and when Sir Syed knocked at the door and called out the inmates, his mother recognized his voice. Mothers are like that. They never fail to recognise their children whatever the condition. His mother cried out:” Why have you come here? Here people are being killed. You go back.” His mother opened the door only after Sir Syed assured her that he had contacted governor of Delhi and other British officers and had secured necessary permission.

His mother and an aunt had lived off horse feed and had not had a drop of water in days. Many wells in the city were filled with corpses and those left untouched had no buckets to draw water with. He went out in search of water and was shocked to see the wilderness all around and, after he couldn’t find a bucket on the wells, he ran to the Red Fort and brought a mug full of water. Oh God, I feel sorry for those who callously and carelessly waste water.

On his return, he found Zaibun sitting on the road with a pitcher in hand. She too had come out to fetch water but due to fatigue and exhaustion couldn’t proceed. When Sir Syed tried to give Zaibun a glass of water, she put it inside the pitcher and pointed him towards the house. She wanted to take water first to her mistress, Sir Syed’s mother. Sir Syed went inside, gave water to mother and aunt and came out to arrange for a carriage to take them to Meerut. He saw Zaibun lying on the ground, dead.

Sir Syed brought his family to Meerut and put them up at a friend’s house as the rebels looted and destroyed his house. His mother who had suffered nervous breakdown during the Holocaust in Delhi could not recover and died within weeks of reaching Meerut.

In 1858 Sir Syed was transferred to Moradabad as Sadr us Sadur (Judicial Magistrate). It was in Moradabad that he wrote Asbab Baghawat-e-Hind (Causes of the Indian Mutiny), a brave book by an Indian servant of the British Raj.

When the famine broke out in 1860, J Stratchey, the Collector of Moradabad, entrusted Sir Syed with the task of organising relief works. With diligence, he saved around 14000 starving people by taking relief to them. Apart from supplying food on war footing, he set up a 24×7 dispensary. He would visit relief camps twice daily and even washed soiled clothes of people suffering from diarrhoea. He nursed the ill back to health. Raja Jai Kishan Das who had thought that Sir Syed was a great fanatic because of some of his writings was moved by the great humanitarian works of Sir Syed during the famine. Das later wrote: “The affection and sympathy with which he was behaving with men of all religions and all castes made my heart clean towards him. I was in fact struck with wonder when I found what a noble soul he was. It was on that day that I established friendship with him, which went on increasing day by day.”

Sir Syed and Raj Jai Kishan Das became lifelong friends. From here on, Das became a constant companion in Sir Syed’s mission: establishment of Muhammadan Anglo Oriental (MAO) College. When the committee was formed to select a suitable site for the College at Aligarh, Raja Jai Kishan Das was on it among five others. Though the College was established on May 24, 1875 and classes had started, Lord Lytton, the Viceroy of India, laid the foundation stone of the College on January 8, 1877. In his address Sir Syed said: “… this is the first time in the history of the Muhammadans of India that a college owes its establishment not to the charity or love of learning of an individual nor to the splendid patronage of a monarch, but to the combined wishes and the united efforts of a whole community. It has its origins in causes which the history of this country has never witnessed before.”

Several Hindu friends of Sir Syed contributed to the college funds. The Rajas of Benares, Vizyanagram and Patiala contributed too. Inscribed on the slabs of the Strachey Hall at MAO College which blossomed into Aligarh Muslim University in December 1920 (it is going to celebrate its centenary this year), among the names of donors, are 10 Hindus. When Sir Syed died in 1898, there were 285 Muslim and 64 Hindu students, many of them residing in hostels. Among the seven Indian members on the staff, two were Hindus. Mathematician Prof J C Chakravarti and Sanskrit scholar Pandit Shiva Shankar were renowned teachers at the College.

So how did MAO College-AMU remember Raja Jai Kishan Das? It named a hostel after him.

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog.