M. A. Siraj

Mumbai’s erstwhile quiet neighbourhood of Mahim has been home to a family that pioneered the first commercial sea voyages for Hajj pilgrims. Though some of the members of the illustrious family still reside in a seaside bungalow, splinters have moved abroad and spread across the world. Even as the family is credited for introducing the steamship service between Mumbai (formerly Bombay) and Jeddah, it was a third generation descendant of the family who was instrumental in raising the Mumbai’s Baitul Hujjaj (Home for Hajis or pilgrims), the most impressive Islamic landmark to be built after 1947 in the city.

Khandwanis are a known name in Mahim. It is they who introduced the first commercial shipping between Bombay and Jeddah for Hajj pilgrims and cargo during an era the world was in the throes of the First World War. They were also the first ones to take a motor car to the desert Kingdom and introduced the first bus service between Makkah and Madinah. With clan having long been spread out between the holy land and Mumbai, and their shipping service merely a forlorn memory, Khandwanis could be found in many parts of the world.

However, from the residual family rose the veteran Mohammed Amin Khandwani who represented the area in the Bombay Municipal Council for 27 years, was an MLA in Maharashtra Legislative Assembly for one term and more notably was the chairman of the Haj Committee of India for seven years, a tenure that saw the construction of the Mumbai’s Baitul Hujjaj. Several icons of the family’s philanthropy during 1920s and 30s survive the vagaries of time.

Deal struck

Khandwanis were four brothers, Abdullah Mian Khandwani, Dadamian Khandwani, Mohammad Mian Khandwani and Abbamian Khandwani. It was around 1914 that they were out on a horse carriage inspecting the Ballard Estate, the property of the Bombay Port Trust put up for sale. The fuse had just been lit for the First World War. Economy had begun to take a beating. Commercial shipping was undergoing a rough patch. The sight of the three German ships standing in the placid waters caught their eye. Discreet enquiries revealed that the ships were up for sale. These were 1-S. S. Vergemere, 2-S. S. Belvedere, and, 3-S. S. Lava. The family struck the deal and ended up buying the three vessels for a princely sum of Rs. 980,000 instead of the Ballard Estate.

Thus began the riches to rags (repeat riches to rags) story of the Khandwani family. The brothers incorporated the Khandwani Steam Navigation Company and embarked upon ferrying the pilgrims during the Hajj season. As for the rest of the year, they sailed as cargo vessels, mainly carrying the food grains to the perpetually famine-stricken Hijaz region of the current Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Fares for the Hajj voyage would peak up to Rs. 210 and ebb down to Rs. 10 per person for those who could not spare more. Booking manager had instructions to insist on people paying according to their status, more in line with the spirit of the Hajj. But pay they must. Company’s heralds (dhandorchi) would go around Muslim localities of the city beating drums. Sans passports and visas, the pilgrims would flock to the embarkation point. It would take the ships ten days to ferry the pilgrims to Jeddah. The company would not insure the vessels going by the then prevailing Islamic prohibition of the Insurance.

Tying a talisman

Amin Khandwani had told this scribe in a long interview in 2005, “My grandfather Abbamian Khandwani would tie a talisman on the mast and sail off for Jeddah”. He also recalled that not too long ago a former porter of the Mumbai dockyard, Abdul Jabbar had approached him (Amin) while Amin held the reins of Central Haj Committee as the Chairman (during 1982-89). He told him that he had travelled in the company’s ship by paying just Rs. 5. Jabbar recalled that Amin’s grandfather would not let him board the ship free, lest Jabbar’s pilgrimage suffer from a deficiency in the sight of Allah. So a token amount of Rs. 5 was collected towards the fare.

Diverse tastes

The First World War ended in 1919. Time flew by. The four brothers grew in fame as well as riches. Eldest among the four, Abullah Mian Khandwani was a good marksman, an expert swimmer and an excellent equestrian and could speak eight languages fluently. He married an extremely beautiful woman from Istanbul, introduced to him by the Sheriff of Makkah. Dadamian (real name Habeeb) studied at Makkah. One of his batchmates, Abul Kalam Azad rose to become the leading light of India’s freedom struggle and became the first education minister of free India in Prime Minister Nehru’s cabinet. His scholarly upbringing made him a book aficionado. He enjoyed the company of sufis. Third in line, Mohammed Mian resembled the British monarch George V, wore Fez cap and pressed flesh with the members of the Bombay elite during evenings at the West Indian Club. Abbamian, the fourth of the Khandwani clan will hold the fort back at Bombay and look after the family affairs.

Bedouins’ wrath

Ships owned by the Khandwanis were key suppliers of food grain to merchants of Hejaz and their arrival at the Jeddah port would be keenly awaited. Often Sheriff and his men would show up at the Jeddah dockyard. It was in 1918 that one of the Khandwanis carried a car and a generator to be gifted to the Sheriff. A large Sedan with a collapsible canvas hood, the car caught the eye of the Arabs. Bedouins dubbed it ‘Satan’ and waited for an opportunity. They could barely withstand its sight. Superstitious as they were, they wondered as to how something could move without consuming fodder. They burnt it down while on a trip to Taif as soon as the opportunity presented itself. As Amin had recalled the accounts related by the elders, the car could not survive beyond 40 days.

Bus service

The Khandwanis were also the first to introduce the first bus service between the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah. Family accounts record that the journey took 14 night for the bus to cover a distance of 425 kms. Torrid heat would not allow the travel during the day time when it would halt on midway stops. A dirt track was all that stood for a highway. The bus would frequently get stuck into the sands. Pilgrims would then be asked to get down, slip wooden planks beneath the wheels and push the vehicle out. The wooden planks would then be shifted to the roof. The family ran the bus service till the early 1930s when Hejaz came under the reign of current dynasty. The Kingdom’s government acquired the bus under Makkah Electric Company and the family was allotted shares in the Company. The descendants of the Saudi branch of the Khandwani clan receive the dividends of the Electric Company stocks till this day.

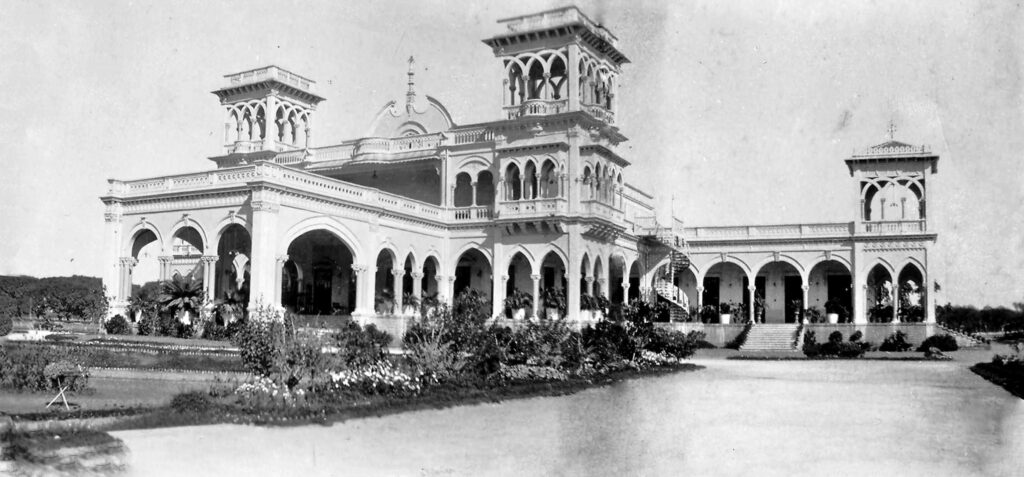

Mansion at Pune

Family fortunes soared, as the riches grew. The family’s house in Makkah was located cheek by jowl with the Grand Harem Mosque. Often the Sheriff’s family hired the house to stay during the pilgrimage. The family acquired huge parcels of property in Mumbai and Pune (then Poona). Amin informed that the Pune bungalow (see the photo in colour and B&W) was purchased at a cost of Rs. 2.5 lakh, a fabulous sum by standards of those days. They employed 107 employees as malis (gardeners) to maintain the 99-acre garden estate. According to Abdullah Khandwani, a cousin of Amin and an art photographer (holding doctorate in Art Photography from the famed J. J. School of Art) who now lives in Toronto, the bungalow’s central hall had a dining table that could seat 76 persons around. Another of the heritage value building that the family built was the Zariwala Orphanage in Mahim. It was demolished in 2003. It sheltered riot victims in 1993. Amin recalled that it was a heritage building and could not provide any photographic record. A Google search does show a building by name Zariwala Orphanage which however bears no hoary look. Amin said the building sheltered over 3,000 riot victims during 1992-1993 communal riots. They also built a 17-room sanatorium in Mahim. Mr. Suhail Khandwani, a scion of the family in Mumbai, shared the photographs of the old edifice which is in use till this day.

Fortunes sink

But then the family’s fortunes made a downswing in 1922 when its ship S. S. Belvedere sank in the Arabian Sea. The telegram carrying the message came as a thunderbolt exactly when the family members had gathered at Poona for the housewarming ceremony at their new, sprawling bungalow.

Auctioned off

Since the ship was not insured, liabilities to be paid were huge. Six years later another ship sank off Bombay coast only to add to the financial woes of the family. All the family’s 76 properties were documented on a register and were auctioned off to pay off the liabilities. Downslide went unarrested. Family women were asked to gather their jewellery on the large dining table. The pile that formed was huge enough to obscure the sight of people on the side of the table.

Heirloom sold

Amin was born to one of the four sons of Abbamian Khandwani in 1932, shortly after the economic downswing had set in. Family silver and heirloom went up for sale. It did not take much time for the family members to get dispersed. Amin had recalled that he had to dispose off a large sized compass, several cupboards full of books, expensive silver cutlery used on board and countless pieces of ornate furniture from time to time. But a bundle of Russian Roubles paid for fare by some unknown passenger bearing dates of 1898 and 1910 and still carrying the pictures of Czarina were found stacked in a cupboard in the company’s office at Ballard Estate. A large-sized book titled Life of Mohammed: The Prophet of Allah by E. Dinet and Sliman ben Ibrahim and illustrated by E. Dinet (pages ornamented Mohammed Racim) survived the squandering of the heritage (see Amin leafing through the book).

Seniors depart

Heartbroken at the downturn of family’s fortunes, Amin’s grandfather, Abbamian Khandwani set sail for Makkah. Hit by a sunstroke, he died there in 1935. Abdullah Mian Khandwani, the seniormost among the family was shot dead in 1935 in Taif after a court intrigue and was interred into the graveyard there.

Shipwreck detected

I met Amin Khandwani in 2005 in his Mahim house, in itself no less than a mansion that few can afford in Mumbai. But Amin informed me that this used to be the guesthouse for the family in 1920s and 1930s. Amin had recalled that some 30 years ago, (prior to 2005), he had received a letter from a British firm informing him of the shipwreck of S. S. Belvedere being located in the Arabian Sea. But then, the cost of rescue operation outweighed the price the metal would yield. The family did not pursue the matter.

Amin had said he, as a young man had looked for a job for long. Someone from the acquaintances had come to his mother and offered to place him as a cinema hall ticket collector referring to her own son serving there. Amin’s mother had refused the offer, telling her that the family traditions did not allow a job of the ilk.

Haj Committee Chairman

Amin built up a career in business to regain some glory. He rose to become the Chairman of the Central Haj Committee of India in 1982. Be it in Bangalore, Delhi or Mumbai, Amin Khandwani would not forget giving this scribe a phone call and chat for a while. He passed away in 2016, leaving a trail of memories that would remain indelible.

M.A. Siraj is a senior journalist based in Bengaluru