Faridoon Shahryar is four years younger to me. I am 50, he is 46. By the time I took baby steps in the world of print by writing letters to editors of English dailies in Patna and elsewhere, he was already getting his poems published in literary journals in India and abroad.

While I sat with a typist to get my missives typed—I later learnt typing at a training institute which came to immense help when I entered journalism—Faridoon would sit with a typist at Shamshad Market at Aligarh to get his poems typed before posting them to publications in the UK and the USA. Those were pre-internet days and many youngsters cannot believe it took 10 days for a letter to reach England.

Son of renowned Urdu poet Shahryar—his lyrics in Muzaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan and Gaman got him wide acclaim—and English teacher at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) Najma Mahmood, Faridoon grew up in an intellectually vibrant atmosphere. Abandoning the idea of becoming an engineer, he took admission in BA (English literature) and read almost everything that he could lay his hands on. While boys and girls his age on the campus were glued to TV, he shut himself away from the idiot box, devouring books with a dictionary, his constant companion. “I began thinking in English. So English was never an alien language to me. I began learning English idioms and metaphors voluminously as I read voraciously. Writing poetry came to me naturally,” he tells me over sips of Cappuccino at a Café Coffee Day joint in Mira Road, a Mumbai suburb. By 21, his poems had been published in literary journals with famous poets like Kamala Das, Shiv K Kumar and Tabish Khair. But then writing poetry alone cannot sustain you. He had to find a profession to earn bread and butter. Since he loved writing in English, journalism was the right choice to move to.

He had a great start as a journalist. A training course at Times School of Journalism in Delhi is supposed to open doors for truly enterprising and hardworking students. His pieces on culture, music and arts did appear in feature pages of the TOI. While interning with the now long-defunct fortnightly Nation & The World published from a floor at a beautiful Bungalow in Nizamuddin West, New Delhi, I remember seeing Faridoon’s pieces in the Sunday Review, the glossy, good weekly supplement of the Sunday Times of India. Nation & The World too had carried some of his poems and I envied him for that. I thought he was destined to reach the top in print journalism.

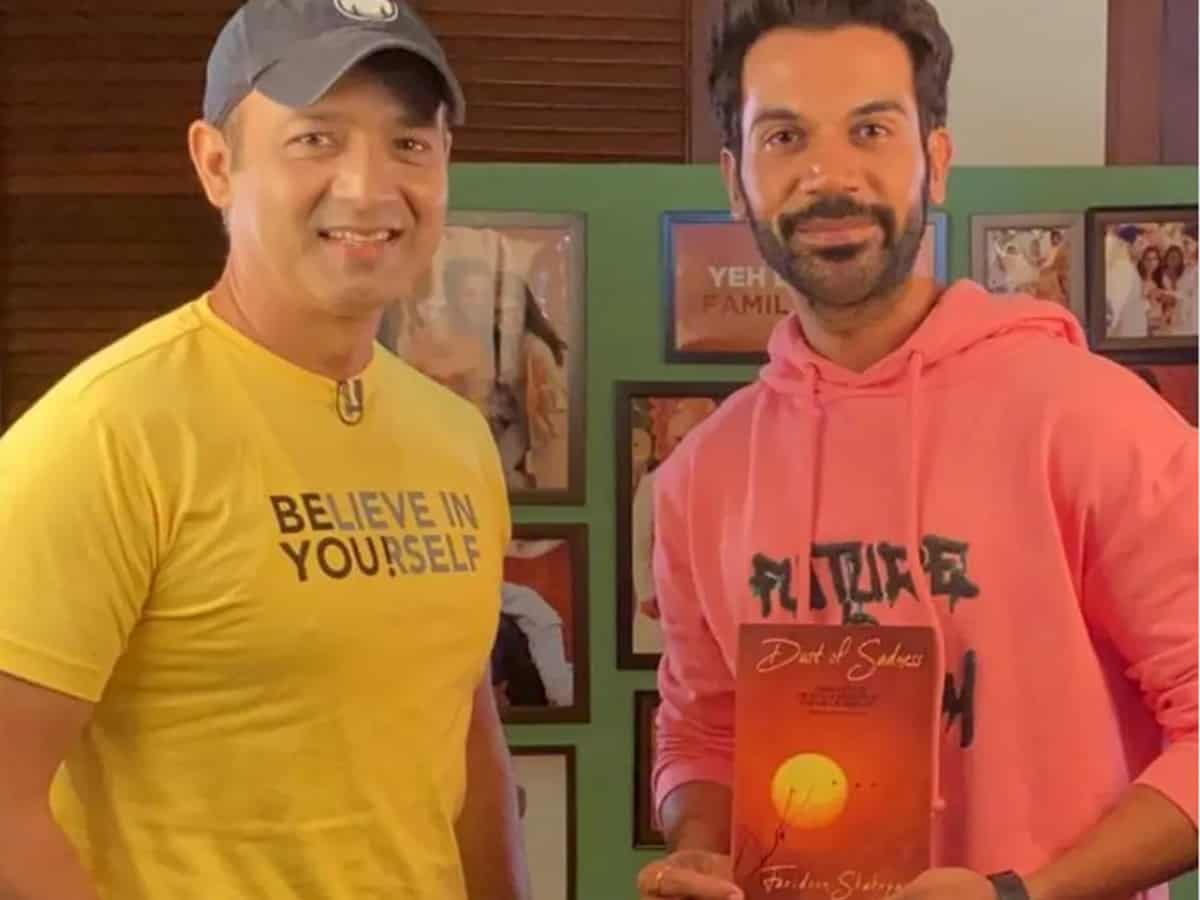

However, he got besotted with cinema and he got drawn to film journalism. It brought him to Mumbai where he went on to create a hungama as content head at Bollywood Hungama, a digital media entertainment platform. It has catapulted him to huge recognition. Moving with the movers and shakers of the tinsel town, the tall, handsome (result of regular exercise) boy in the golf cap knows the industry like the back of his hand. Many stars are on his speed dial (caution: don’t approach him for anyone’s contact or with a request of introduction. You will be disappointed).

To be on Faridoon’s show is a privilege, and a ticket to instant publicity, which no stars or starlets, directors, music directors or lyricists can afford to miss. His work has taken him to all corners on the planet–Busan today, Bali tomorrow, Bangkok the day after. He has grabbed so many awards and citations from film and entertainment organisations in India and abroad that I once joked: “Faridoon, you need to get a separate house to keep all those awards and citations.”

That he has just come out with ‘Dust of Sadness’ (Kavishala), his first poetry collection, is no surprise to me. He had to come out with an anthology; the surprise is why it took so long for someone who began writing poetry so early (he wrote ‘Echo of expectations’ at 19 and says it has withstood the test of time). Sample these lines from the poem:

‘An echo of expectations,

Resonates profusely

In a dim-lit room

A shadow of dreams

Saunters along,

Halting briefly

To move again,

Lost in its reverie.

It is a sin to expect,

The voiceless screams.

The sleek book is divided into two parts. The first section named ‘Innocence…in search of maturity’ carries poems penned between 17-21 years of his life. The second section named ‘Maturity…in search of an escape includes poems written when he was between 37 and 42. Penned with great passion, the poems show the empathy, the concern he carries for the world. Creative minds find catharsis in their creations. Writing a poem, an essay, you feel a rush of creative juices with therapeutic impact. A poet is restless unless he has poured his heart out and taken the burdens, he carries off his chest. Faridoon is no stranger to this syndrome.

Of late, he has begun doing something that was a bit unexpected from a full-time journalist. He decided to record interviews with some of the living legends of Urdu literature. Before death took litterateur Shamsur Rahman Farooqui away from us, Faridoon had captured some of his thoughts on life and letters for posterity. He watches his guests’ lectures and interviews innumerable times on YouTube before he poses his own questions to the legends. He employed the same technique while interviewing the likes of Iftikhar Aarif and Gopi Chand Narang. Result: immensely enjoyable interviews on videos. They will help future historians of Urdu literature read the minds of these great writers, poets and critics before they write their own books.

Age is on Faridoon’s side. So is his indefatigable enthusiasm to interact with people of ideas. We expect more books from him. And not just poetry collections. An insightful book, based on his own interactions with people in Bollywood, is a sure shot bestseller. Once he ghostwrote a book for someone else and was paid handsomely. It is time to write his own book in prose.

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog