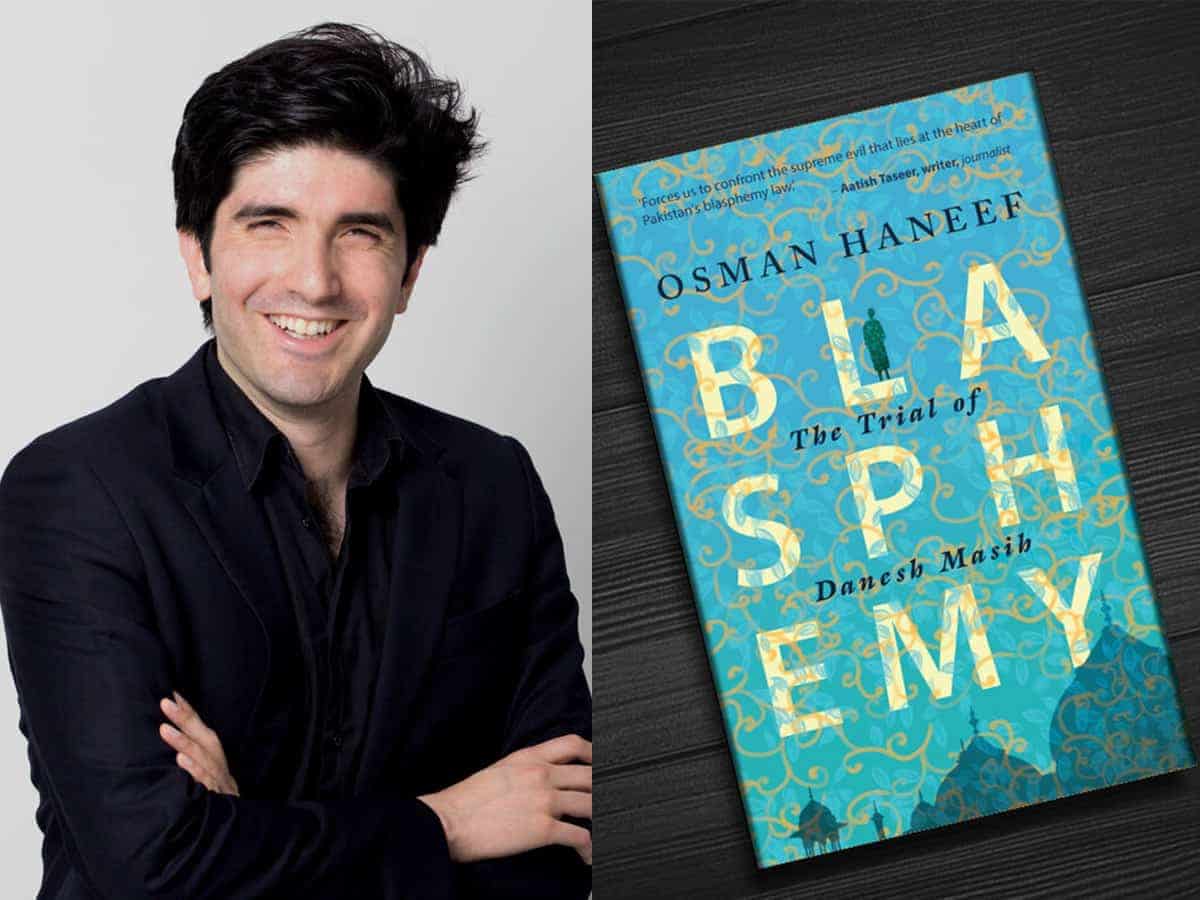

New Delhi: Author Osman Haneef, son of a diplomat, was born in Pakistan but grew up in different cities in Asia, Australia, Europe, and the Middle East. This largely shaped his liberal outlook and has translated into a novel that points to the hypocrisy of a country’s laws that are ostensibly meant to prevent blasphemy but in reality are perverted to target the innocent.

“Over a decade ago, I started the novel as a ‘discovery’ writer. That is, I wrote the first draft without a strong sense of the narrative arc or the central conflict. The initial draft focused on a protagonist still finding his place in the world, familial conflict, and a doomed love affair,” Haneef told IANS in an email interview from London, where he lives with his family.

As he wrote, his mind kept coming back to a blasphemy case from the 1990s in which renowned human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir defended an illiterate Christian boy, Salamat Masih, who was accused of writing blasphemous statements on the wall of a mosque in his village in Punjab.

“There was no physical evidence, and the judge was never told what was said — because to repeat the statement would have been blasphemous. One of Masih’s co-defendants was killed, the lawyers were repeatedly threatened, and a mob at the High Court smashed Jahangir’s car, assaulted her driver, and threatened her with death.

“Eventually, the conviction was overturned, and Masih fled to Germany. However, the injustice to an obviously innocent young boy wrongfully convicted in this Kafkaesque court proceedings in Pakistan stayed with me. I couldn’t write anything else.

“After the first draft, which felt like it belonged to two different genres, the real

work began and the revision process took me several years. Eventually, I brought the disparate strands together,” Haneef said.

The outcome is ‘Blasphemy: The Trial of Danesh Masih’ that has been released in India as an ebook by the publisher, Readomania. Not surprisingly, it is highly unlikely to be published in Pakistan.

The book makes for some sobering reading.

Danesh Masih, a Christian boy, is accused of blasphemy — a crime punishable by death. Haunted by a tragic past, a young lawyer named Sikander Ghaznavi returns to Pakistan after living abroad for many years, and takes on the defence of the boy. Out of his depth, Sikander reaches out to the sharpest human rights lawyer he knows — the woman he has loved for years, but is now another man’s wife. As they deal with their unresolved feelings, the lawyers confront a corrupt system, a town turned against them, a radical religious leader, Pir Piya, and a prophecy that predicts their death.

Towards the end of the novel, Danesh is killed outside the courthouse, and his family seeks asylum in Canada. Sanah, the lawyer, stays with her husband. But Sikander continues to pursue justice as a human rights lawyer and defends Aasia Bibi, also accused of blasphemy, a decade later. The government arrests Pir Piya and the members of his radical religious group who demonstrated against the acquittal of Aasia Bibi. For a brief moment, justice prevails.

A considerable amount of research went into the writing of the book.

“Much of my lived experience ended up in the novel. My parents are from Balochistan —

so many summers and holidays were spent in Quetta. The sense of the place I captured through those trips, the places I visited, and the people I met. I have seen dementia in my family, so I was able to capture it in my novel. But I also borrowed from other sources. I researched almost every little thing that was outside my own experience, for example, what happens when your jaw breaks? I looked it up,” Haneef said.

For the courtroom scenes, he visited the courthouse in Quetta and watched some of the proceedings. He spoke with human rights lawyers about their experiences in Pakistan. He read the records for different blasphemy cases and then had experienced lawyers review certain facts and proceedings.

“Asad Jamal, a prominent human rights lawyer in Pakistan, actually commented that ‘anything is possible’ in a Pakistani courtroom because he has seen everything. So, I shouldn’t worry too much about credibility,” Haneef pointed out.

For the extremist characters and radicalisation, he had actually studied the topic over several years in university. At Yale, he received a fellowship to retrace part of Che Guevara’s route in his Motorcycle Diaries. He travelled through Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Bolivia, and remembers seeing different forms of extreme ideologies based on socio-economic backgrounds rather than religious identity.

“My experience revealed that education does not necessarily lead to enlightenment, and intolerance is a disease that is not limited to a single faith, ideology, or country. The novel illustrates how laws and ideology can be perverted to target the innocent,” Haneef said.

What of the future?

“We are still looking to launch the paperback a few months after the lockdown (ends). I hope that I will be able to visit India for an in-person launch someday although it seems challenging, given how restrictive the current government has been with visas,” the author said.

Beyond that, he hopes to continue to write novels, books, and articles “that address global issues that matter. In a world facing a resurgent wave of fascism and ethno-religious nationalism, where minorities are used as scapegoats, those of us with privilege and power must speak for those who cannot defend themselves”.