Away from the crammed, cacophonous life in a metro and devoid of the divisive slogans like “goli maro” and “current to Shaheen Bagh”, I recently spent a peaceful week at my ancestral village in Bihar.

It was my beloved father’s first death anniversary and my siblings and I decided to remember him by doing something which would have pleased him immensely had he been alive today. Since he was a school teacher and had spent his life teaching and guiding students, we decided to do our bit for some of the students in our village.

I asked my cousin Rashid Sami to prepare a list of boys and girls in the village who had passed an exam last year with flying colours. Around a dozen made it to the list. At a modest function we distributed certificates of merit and medals among those whose name appeared on the list.

The beautiful, brief ceremony was different in many ways.

Though predominantly Muslim, my village is divided into three tolas or small hamlets. So, apart from Muslims, there are houses of banias called suris, cobblers or mochis and mushars who are so poor that some of them eat rats and are now among Maha Dalits in Bihar’s entrenched caste hierarchy.

I grew up seeing mochis and mushars working as farm labourers for the high caste zamindars of another village. The suris were engaged in small trades and they had opened kirana or grocery shops or sold grains at weekly haat or village bazaar. None of the suris in my village till a decade ago had studied beyond matriculation while most of the mochis and mushars remained unlettered and dirt poor.

During lean or non- farming season in their state the men from mushar and mochi tolas went to Punjab to work in the fields and earn livelihood while women stayed back bringing up children. Even as I turned 14, passed 10th exam and left village to study in a town, I had not seen a mushar or a mochi child of my village studying beyond primary level.

Uneducated, undernourished and without much scope where they lived in, the boys migrated to big cities to slog as unskilled workers while the girls were married off early. For them, the village remained an area of darkness while the big cities brought relief from pangs of hunger.

Higher education was beyond their reach. These children of a lesser God didn’t aim for big in life. Almost every man drank tadi or Toddy. The suris were not so poor but giving good education to their children was not among their priorities.

Which is why I was enormously glad when I found a suri, a mushar and a mochi boy on the list of candidates we were going to felicitate. Chanchal Mahtha, son of Kanhaiya Lal Mahtha, a suri who works as an LIC agent, cracked the Sub-inspector of Police exam last year and is currently training. He will be the first boy from my village to become a daroga or Sub-inspector.

Kanhaiya came to receive the certificate and medal on behalf of his son. He later told me that Chanchal wept on phone after he saw his father in a video receiving a small token of appreciation from us. “Papa, nobody among our relatives thought of giving me an award. But these uncles from our village have made us feel proud,” said Chanchal to his father on phone. Both father and son were flooded with phone calls from their relatives as they shared photographs and videos from the award ceremony on WhatsApp and Facebook.

The story of Dilip Kumar Ram, the boy from mochi caste, is more spectacular. His unlettered father Misri Ram worked as a driver in Delhi nursing a dream to see his son become a big man. Misri’s wife Sanjayi Devi stayed in village, determined to educate their son Dilp.

Dilip took a leap of faith when he got enrolled at an Engineering college in Bhopal. Now he is B.Tech and works with a company in Delhi. I had seen in my childhood how the high caste zamindars treated these landless mochis.

They would get the tongue lashes and threats of eviction–they had built their huts on the zanindar’s land –if they refused to work in the fields of the zamindars. These poor mochis didn’t have the courage to sit on chairs before the zamindars and were expected to address the zamindars and their children not by their names but as maalik (lord).

These poor mochis, men and women, would often appear in soiled and tattered clothes. So, my joy knew no bounds when I saw Dilip’s mother Sanjayi Devi come to receive certificate of merit clad in a clean, black sari. I remember many of the mochi women as midwives who wore saris that were often soiled and stained. Seeing Dilip’s mother in a clean, new cloth made my heart fill with pride.

Dilip has broken chains that had tied his community, at least in and around my village, for centuries. The light of education has finally reached the darkest of the corners and we felt honoured to felicitate the likes of Chanchal and Dilip.

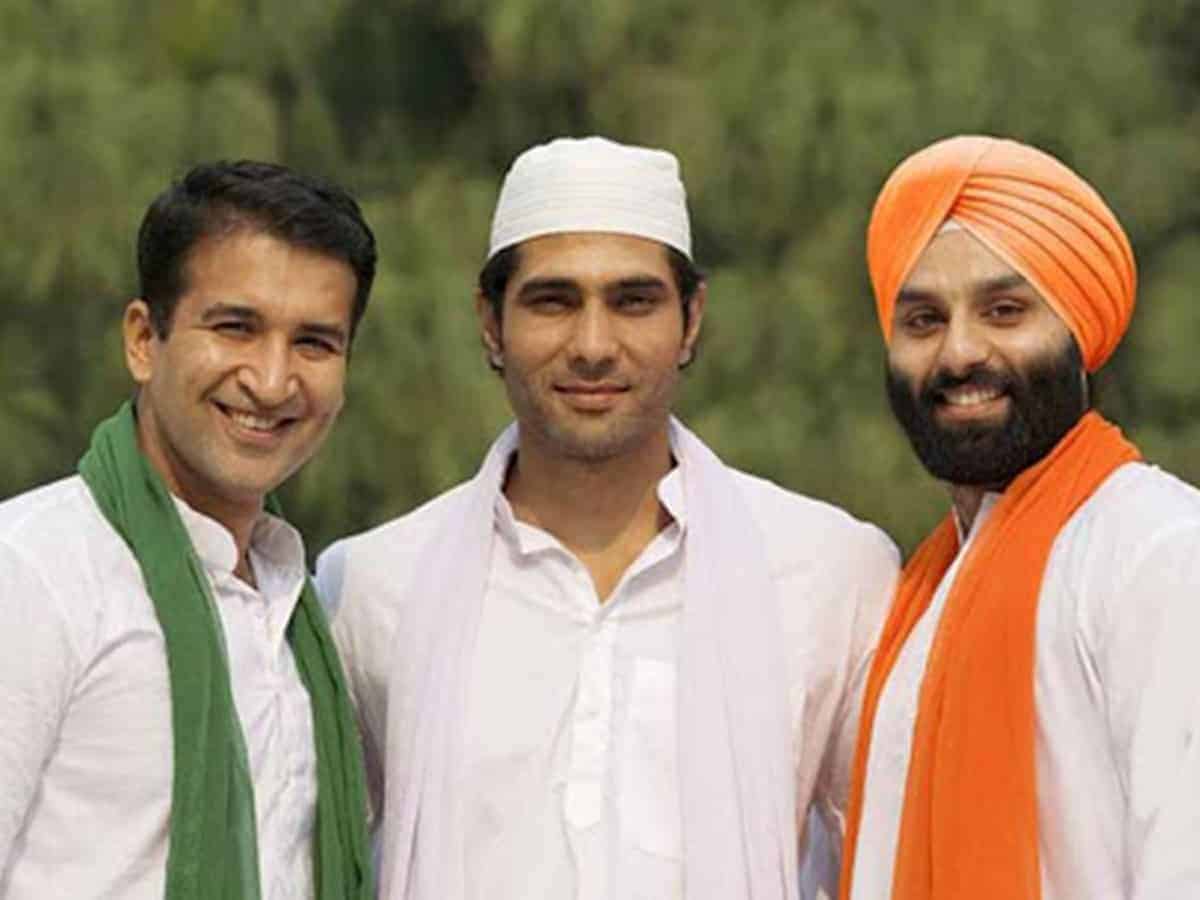

Among the guests who graced the felicitation function was my father’s close friend Ram Babu Jha. He spoke fondly about my late father and appreciated our humble efforts to encourage children to excel in education. My father’s another friend and a fellow teacher at a High School Wasi Ahmed Shamsi lauded the fact that we siblings–our elder brother Quamar Alam Nayyer, younger brother Dr Mohd.Qutbu and I ensured that we included a mushar, a mochi and a suri, along with Muslim children, for the awards.

We sang songs of devotion and we also sang our national anthem together.

We didn’t have money to give them or buy the awardees expensive gifts but the small token of our love and appreciation will hopefully go a long way to spread an atmosphere of goodwill. We have resolved to announce coaching and guidance for poor and meritorious students of our village soon. Caste is no bar and the only criteria to get educational help is merit.

Wasi Ahmed Sahab who taught me Urdu and Persian in High School observed that this small gesture would help detoxify the atmosphere. It will work as an antidote to the culture of hatred being spread in India. This is the way we can defeat the nefarious design of those who want to divide us. This is the way we can help promote harmony and combat communalism. My India is not the land where hate-mongers tell communities to see people of other faiths as enemies. My India is a land where a mushar, a mochi, a Muslim and a suri sit together and celebrate success stories. As long as this spirit of share and care survives, my India will survive. This is my India and we will ensure it survives till eternity.

Kutchh baat hai ke hasti mit ti nahi hamari

(There is something that we don’t extinct/Though the world has been our enemy for centuries).

Sadiyon raha hai dushman daur-e-zaman hamara

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog.