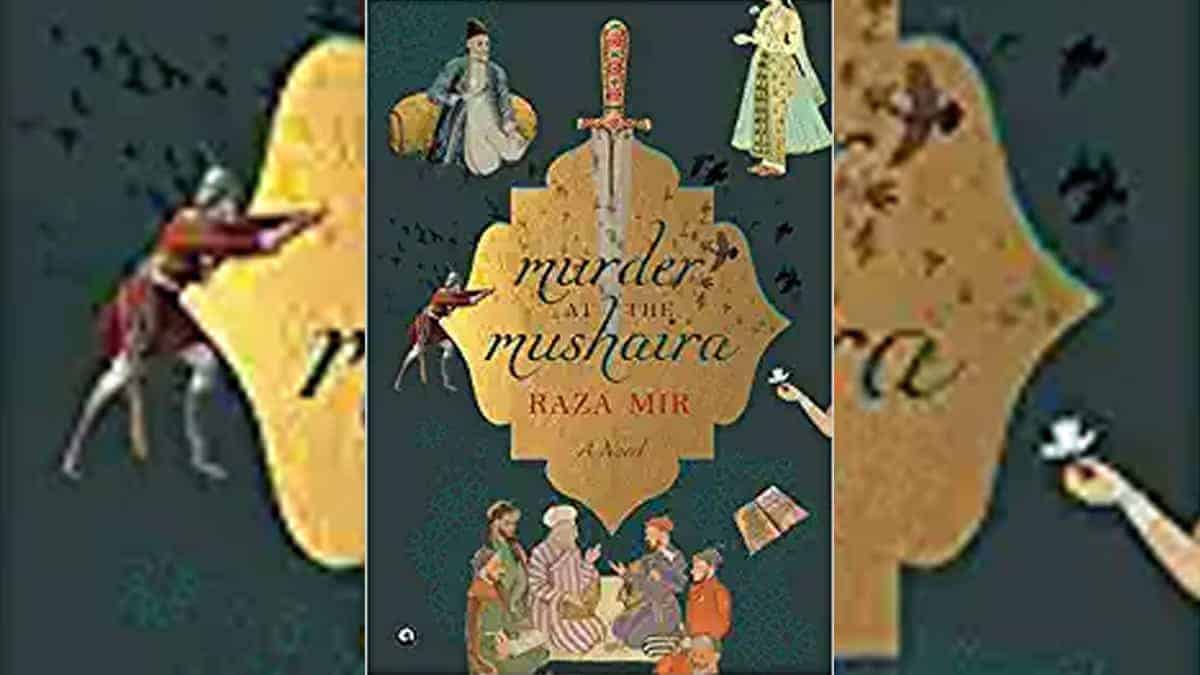

The backdrop of middle 19th century North India has made for some excellent storytelling, be it the Aamir Khan-starrer Mangal Pandey or William Dalrymple’s The Last Mughal. The latter’s influence is apparent in New Jersey-based Management Professor and author Raza Mir’s latest offering, Murder at the Mushaira.

With Mirza Ghalib as the protagonist and a setting around the build-up to the 1857 mutiny against the colonialist British, readers will enjoy the recreation of these events. And those who have seen the 1988 Doordarshan serial Ghalib will feel nostalgic about it. Like Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, every chapter in Murder at the Mushaira is prefaced with a couplet before it paints a vivid picture of North Indian society on the cusp of watershed change.

One may surmise that the author grew up on a steady diet of Agatha Christie and Ibn-e-Safi mysteries. The suspense here revolves around the murder of a shady and shoddy poet who frequents mushairas held at an uppity noble’s palatial residence.

By no means is this creative nonfiction as Mir admits to taking a certain amount of license with real-life personages. The menagerie of characters, their origins, and certain actions (both real and fictional) that take the story forward are fleshed out thoroughly. The espionage element another sub-plot around the explorer-cum-spy-cum-scholar, Mohan Lal Kashmiri, adds an extra layer to the suspense. Kashmiri was a vital asset to the colonial forces during the Great Game, the tussle between the British and Russian Empires for a strategic advantage in Afghanistan —the gateway to India.

Weaving a murder mystery into the milieus of Delhi such as the coteries of Urdu poets, the decadence of the nobility culture overlapping with effects of the Great Game and the Anglo-Afghan war is ambitious. Though in this Who Dunnit?, Raza Mir is very much up to the task.

Nevertheless, unlike many other English and Urdu writers, he does not fall into the trap of paying mere lip service to other regions beyond the present-day Hindi belt.

Those familiar with certain Urdu literary figures who would go onto etch their place in history will love cameos they make as secondary characters. For instance, there is an interaction between a young Daagh Dehlvi asking for Mirza Ghalib’s advice on whether he should make his way to the Princely State of Hyderabad as English had began to supplant Urdu gradually.

The evocative dialogue between the two is effectively well-crafted. While reading this, anyone familiar with Zauq’s repertoire would conjure the Delhi poet’s lines that captured his angst at the mere thought of leaving his home for greener pastures down south.

In dinon garche Deccan mein hai badi qadr-e-sukhan

Kaun jaaye Zauq par Dill ki galleeyaan chhor kar

In the next few lines, Mir’s deft pen then obliges the reader with the second verse of the couplet above. Many such instances that are gratifying to Urdu connoisseurs can be found throughout the book. However, die-hard scholars may take exception to this blending of fact and fiction. For instance, in the same scene, Daagh tells Ghalib that he was invited by “Nizam IV Nasir-ud-Daula and his then heir-apparent Afzal-ud-Daula to become the poet at the King Kothi of the Asaf Jahi Dynasty.”

Like professors adept at spotting the slightest deviations in a historical fiction movie, Urdu academics will state with certitude that Daagh was not invited by the fourth or fifth Nizam. The poet, now buried at Yusufain Dargah, went down south of his own volition to Asaf Jahi-ruled Hyderabad.

Other purist Urdu-daans may even balk at the way Ghalib’s verse “Kuch to paighaam-e-zabaani aur hai” is instead written as “Koi to paighaam-e-zabaani aur hai.”

Nevertheless, the author should be credited for going beyond the stereotypical, glamourous depictions of the feudal and the standard caricature of the cunning, oppressive British soldier. Those accustomed to portrayals of the delightful aspects of the aristocracy will not like Mir delving into the nobility’s dark side.

All in all, Raza Mir has penned a fun mystery that introduces English-speaking readers to a bygone area that saw the erosion of a civilization — one seen in some Bollywood films, Urdu novels, or some of their translations. For Urdu readers, it would certainly not be too much to ask for a translation.