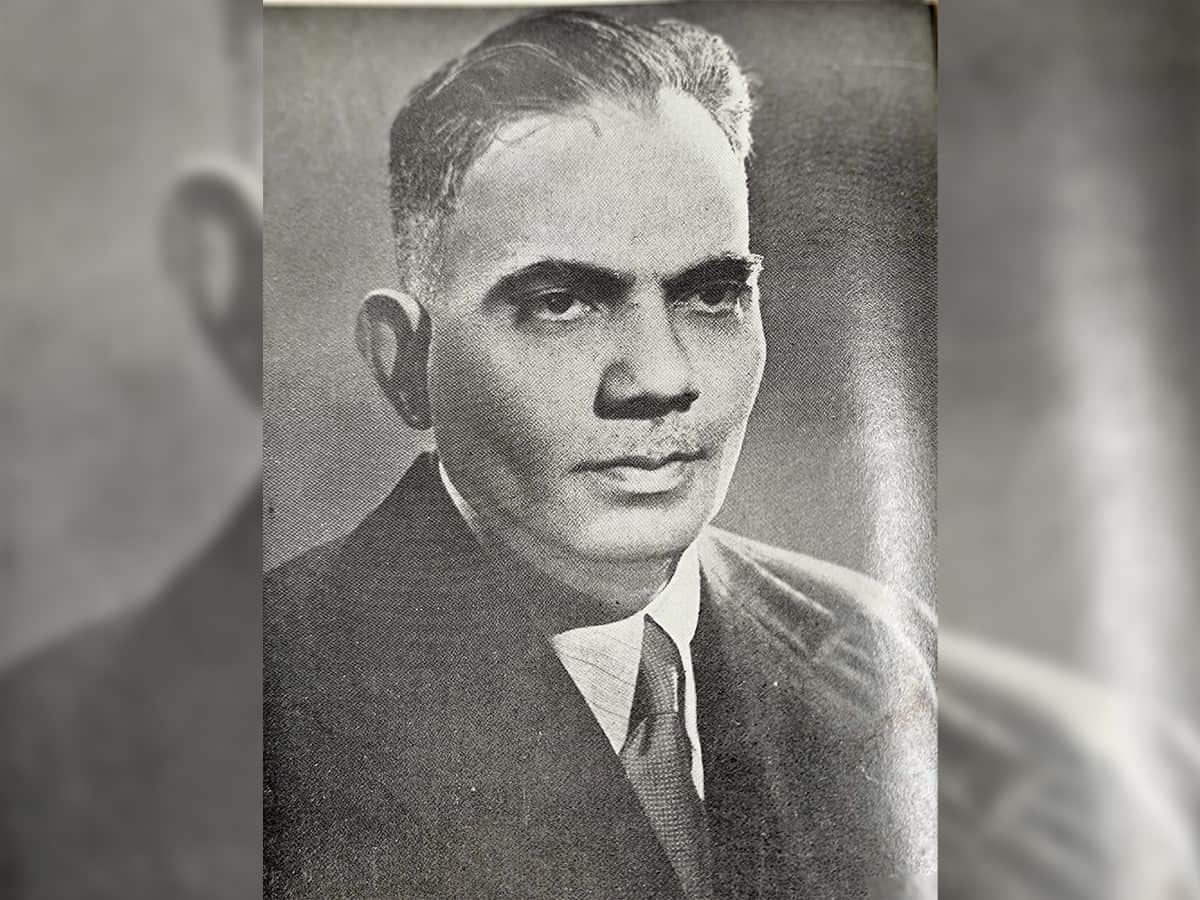

Of all the political absurdities leading to the forceful annexation of Hyderabad state to Indian Union, nothing perhaps is more perplexing than the appointment of an engineer-turned-businessman with no political experience whatsoever to the highest post of Nizam’s ministry during the most crucial time in Hyderabad’s history.

Mir Laiq Ali appears on the scene right after Standstill Agreement between India and Hyderabad was signed on November 29th, 1947 following which the Nawab of Chattari vacated the Prime Minister’s post. The PM’s office took a toll on Chattari’s health resulting in a series of heart attacks. Such was the prevailing political tension in the state. To add to it, he was a ‘Non-Mulki’ as was his predecessor Sir Mirza Ismail and the public sentiment was rising against the ‘Non-Mulki’ dominance in the Nizam’s government.

Mystery of Laiq Ali’s appointment

According to Laiq Ali, he had politely discouraged Nizam’s initial “general exchange of views” on the matter of his appointment to the office. Laiq Ali previously had declined the offers of joining Sir Akbar Hydari’s and Nawab of Chatter’s cabinets. However the Nizam persuaded him persistently. Apparently he was also approached by “scores of prominent citizens of Hyderabad of whom a good many were Hindus”. Why a businessman with large industrial stakes in Hyderabad and Pakistan became a frontrunner for Prime Minister’s office is strangely left out from Laiq Ali’s voluminous memoir, The Tragedy of Hyderabad. Nevertheless his memoir happens to be the most comprehensive account, sometimes a day-to-day account of mayhem within Hyderabad state affairs leading to the D-day despite some logical blanks here and there.

Thankfully the readers have alternate sources to fill in the blanks with especially coming in handy on the matter are the then Constitutional Advisor Ali Yavar Jung’s series of articles published in Times of India even if K M Munshi’s accounts could be discounted as biased.

That Laiq Ali was in good books of Mohammed Ali Jinnah with whom the Nizam was exchanging political thoughts during the time does not make Laiq Ali’s candidacy seem like a coincidence. Laiq Ali suggests him and the Nizam shared a mutual attitude on Pakistan, that of unfettered affection and that he had finally accepted Nizam’s invitation in December 1947 not without obtaining Jinnah’s “permission” first. Ali Yavar Jung doesn’t mince his words speaking of Laiq Ali’s appointment as being “installed on the recommendation by the Ittehad and as an acceptable Mulki” with the blessings of Jinnah. His only other contender, Mr. Gulam Mahomed had already accepted Finance Ministry of Pakistan.

Ali Yavar Jung shares a ray of hope that prevailed in Laiq Ali’s initial days of ministry that he began by releasing State Congress members from jails who were imprisoned for their indulgence in satyagrahas across the state. Moreover the fact that he had a lot of Hindu friends in the profession of industry had the potential to diffuse the communal tension Ittehad had already created. The thought was he would “rise to the occasion during the grace period of Standstill Agreement to the good purpose of an enduring settlement of these internal problems.” Instead the talks with the State Congress turned out to be inconclusive and hit a dead-end.

The hope faded away very soon when it became evident that Laiq Ali was seeking council from the Finance Minister, Moin Nawaz Jung who also happened to be his brother-in-law. AYJ points out “a person whose métier was neither politics nor administration was depending on another person with narrowness of political outlook and imagination.” That Laiq Ali had already made an informal arrangement with the Nizam “on the issue of future relationship with India on no account and at no stage to be an accession” is a candid admission in his memoir.

Destabilization tactics by Congress

In Laiq Ali’s defense he gives a detailed account of the various unethical destabilization tactics employed by Indian Congress in the form of constant bullying publicly and privately, border raids that led to loss of lives and property and the worst of all – the economic blockade making Hyderabad’s innocent citizens suffer. Not just limiting there, even the rail networks were disturbed that stalled imports and exports and attempts to seek arms and ammunition foiled. One wonders if 24 hours fell short in a day for the Wazeer-E-Azam to deal with such magnanimity of issues.

Laiq Ali’s boasted vision of himself and mismatched priorities with ground reality reveal themselves with anomalies such as him taking to patronizing a local manufacturing unit of arms and ammunition without consultation with the military and finding time to make trips to Pakistan and advising Jinnah on the issue of Kashmir. By then, Laiq Ali came to realize the canvas of power his role as the Prime Minister offered it seems.

Then came the controversial transfer of securities of 200 million to Pakistan by Moin Nawaz Jung that was considered as a breach of Standstill Agreement by Delhi. However the move gave Laiq Ali a necessary leverage to negotiate relaxation of economic blockade, release of held up imports and exports and acquisition of necessary arms and ammunition to deal with “internal conflicts.” Laiq Ali had promised that he would ensure Pakistan would not place the securities in question on the market during the currency of the standstill agreement.

Ittehad’s takeover

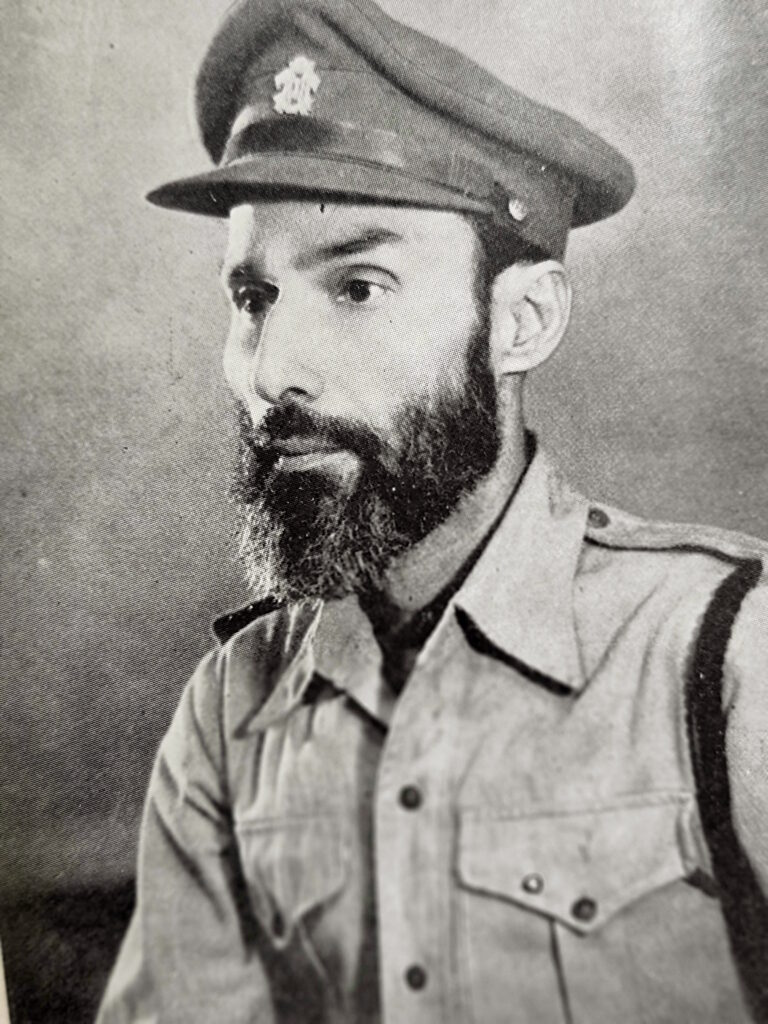

Things would seem to progress if not for the two demands of Indian government discounted by Laiq Ali’s ministry, one that of forming a responsible government of people’s representatives where the executive is answerable to legislation and the second, disbandment of the communal Razakars who took upon themselves voluntarily to guard the honour of one of the last standing Muslim empires after the fall of Caliphate. There is ample documentation out there in public domain that reflects their means to achieve their goal was anything but Islamic. Ironically the Communist movement that was running parallel in the state adhered closely to the ideal Islamic values of equality of men, fighting against the brutal feudal setup under the Nizams.

This is where Laiq Ali indicts himself as the man largely responsible from the Hyderabad government for the debacle to follow. Not only did he completely ignore the warnings but actively financed Razakars, both personally and officially. He further infantilizes the reader in his memoir that the amounts financed were “small”, not enough for Qasim Razvi to have organized a ragtag militia of some two lakh young impressionable Muslim youth. Here is a man who was always dressed in trim western suits as a sharp wall-street businessman of the day capitalizing on the social-cultural and political rhetoric of Ittehad’s Muslim supremacy of “An al Malik” i.e. every Muslim of the state to be a shareholder in it’s power. It didn’t seem to occur to him the kind of effect it would have on the 85% Hindu demographic of the state especially with Hindu communal organizations such as Arya Samaj and Hindu Mahasabha already arriving on the scene.

AYJ reflects on the ground being set unfairly for Laiq Ali to operate ethically as both Bahadur Yar Jung and Jinnah employed double standards when it came to Hyderabad versus Pakistan and Kashmir. BYJ had urged a responsible government in Kashmir but opposed it in Hyderabad. Jinnah demanded partition of India on communal majoritarian politics whereas wanted Hyderabad to remain a Muslim state based on the religion of the ruler instead.

Hence to be fair to Laiq Ali, Ittehad already hijacked the workings of reforms committee and responsible government even before he took to office. Ittehad Muslims formed 51% of the state’s legislature achieved via 50% Muslim reservation and separate electorates and the remaining 49% shared between Hindus, Christians and Parsis. The additional 1% was gained via nominee quota. AYJ calls on this as a violence done to mathematics of representation.

However, Laiq Ali had an opportunity to turn things around when forming his own ministry. He came up with a formula of 4 Muslims, 4 Hindus and 4 officials. The 4 Muslims expectedly came from Ittehad members of assembly, 3 out of 4 Hindus owed their elevation to Qasim Razvi with the remaining one, Pundit Ramachary being a repudiated ex-Congressite nominated by the Nizam. The remaining 4 officials also (un) surprisingly were also selected with the approval of Qasim Razvi and not the Nizam.

Moin Nawaz Jung by then had already took over Police Ministry so not only the legislature and PMO but the law and order also was now completely in the hands of Ittehad’s influence. He also was now leading the Hyderabad delegation to negotiate further terms with Delhi after Nawab of Chattari and Ali Yawar were excused off it and Walter Mocktown retiring to Britain to manage WWII contingencies. It seems like Hyderabad’s government hinged on the whims of these two brothers-in-law with the rest of the government relegated to background including the Ala Hazrat.

AYJ administers the final nail on the coffin of the Razakar movement that they could not have succeeded without the help of the government. The supply of rations, uniforms, fire-arms and training, and payment of allowances to such a large number of men was beyond the capacity of Ittehad despite all the assistance given by the more enthusiastic Muslim industrialists. To save the government from the accusation that it was assisting a communal militia, a page was stolen from the book of Allama Mashiriqi and, as in the Khaskar movement, desirable Hindus were also recruited.”

The Muslim massacre

The last but not the least of immaturities evident in Laiq Ali’s excuse for an administration was his ideological stand off with the Military Commander of Hyderabad, General Syed Ahmed El-Edroos who he thought was not conscious of the gravity of the situation and his professional military gestures were mere imitations without substance”. El-Edroos in contrast gives a more realistic assessment of the state’s military capabilities in his memoir that Hyderabad was in no way or shape ready to face a military offence from Delhi. Qasim Razvi with the support of Laiq Ali had already won over the spirits of Nizam’s irregular armies to operate under the communal rhetoric rather than to take orders from the Military Commander. Laiq Ali even contemplated replacing El-Edroos but ironically found nobody else worthy to take over.

All negotiations had come to an end without a resolution. Qaid-E-Azam passed away on September 11th. Any material or military support from Pakistan suddenly became a distant dream. A public holiday was declared in Hyderabad and mass funeral prayers held at Makkah Masjid. Hyderabad alerted the UN of an impending military offensive by India and yet again it would have to be Moin Nawaz Jung to head this delegation because who else? India attacked on September 13th and finished off the meager resistance within 4 days and secured Hyderabad’s surrender on the 17th.

In the process, one of the most darkest chapters of the subcontinent took place, a repeat of partition-style communal violence which the Sunderlal Committee report documented as a massacre of Muslims especially in Marathwada and Karnataka-Hyderabad regions, aided by outside mobs, communal organizations, the Hindu revenge sentiment from the Razakar violence, all assisted by the military. The committee report conservatively puts the death toll at 27,000 to 40,000 but the unofficial oral accounts puts it at nearly 2,00,000 with rivers, wells, mosques and dargahs overflowing with corpses of Muslim men and women.

The report suggests that the communal frenzy did not exhaust itself in murder alone but also in rapes, abduction of women and children, forceful conversion, loot, arson, desecration of Mosques, seizure of houses and lands etc. Telangana region and the capital city of Hyderabad however remained relatively safer when compared, with several communist leaders of the day recounting their call to Telangana people not to indulge in anti-Muslim rhetoric.

Delusional heroics

Laiq Ali’s memoir continues on to his heroic role even during the military offensive. He boasts of the formidable resistance offered by the Razakars and the state’s irregular forces and that he was personally commanding several units as the military chain of command was dead. According to him even common citizens took up arms to defend the state heeding his appeal on Deccan Radio. Laiq Ali was supervising the demolition of bridges on borders with the help of Public Works Dept who built them in the first place. He was contemplating opening the gates of Himayat Sagar to flood Musi river to prevent the military entering the capital. The Nizam who suddenly realised all was lost yelled at Laiq Ali for a disastrous captainship on his part and retired to his chambers never to fully recover. It was in fact the end of his era. He presented the resignation of Laiq Ali’s ministry the night before the accession to K M Munshi as the vultures have resigned.

Munshi, being the Agent-General of India to Hyderabad who was isolated from the state affairs by Laiq Ali to an extent he wasn’t even able to secure a single meeting with the Nizam recollects the most irresponsible of the discussions he had with Laiq Ali that if all options were exhausted him and his citizens will resort to “martyrdom” but never in their wildest imagination will accede to India. After the Indian takeover, Laiq Ali was put on a house arrest from which he architected a brilliant escape including his entire family to Pakistan.

Firaq Gorakhpuri’s famous couplet lends itself to the collective mourning for the left-over citizens of Hyderabad State – Humein too apnon ne loota, gairon me kahan dum tha, meri kashti jahan dubi, wahan paani kam tha drawing attention to the complexities of the tragedy that could have been completely avoided with an effective statesmanship and internal administration of the State.

Moses Tulasi is a Hyderabad-based documentary filmmaker who occasionally writes on History and Culture.