By Sagarika Ghose

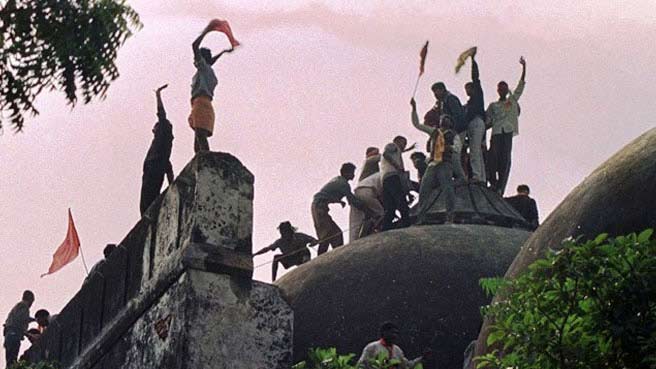

Twenty-five years ago this day Babri Masjid was demolished. On the debris of the ruined mosque rose a new political force which roared out its hatred of “minority appeasement” and “pseudo secularism” and called for assertive Hindu cultural nationalism. BJP emerged as a serious contender for political power at this time and in 1995, three years after the Babri demolition, the saffron party stormed to a majority in Gujarat for the first time and has not lost an election in the state since.

The Ram rath that rumbled out of Somnath in 1990 with LK Advani as charioteer and Narendra Modi as chaperon has steamrolled its way to national centre stage. Hindutva is in power in 18 states and the Centre and a Hindu rashtra is firmly in place in Gujarat. The Hindu chariot appears invincible. But is it? Just as Congress played identity politics under the cover of secularism, now BJP plays identity politics through Hindutva. But does identity politics always win? Or is the ghost of Babri Masjid having its revenge on its destroyers?

Indira Gandhi played identity politics in both Punjab and Kashmir in the early 80s, seeking to create ‘Hindu’ consolidation in both states against the Akalis and Farooq Abdullah respectively. When she was assassinated, she became the first politician who in attempting to ride the identity tiger was devoured by it. Over the decades, Congress’s so called ‘secular’ politics degenerated into a pandering to clerics, priests and identity warriors of all hues, as seen when Rajiv Gandhi overturned the Shah Bano judgment, banned Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, and allowed puja in the Babri Masjid.

Since secularism lapsed into identity politics, it led inevitably to a reaction and mobilisation in the form of a counter-identity, namely Hindutva. Identity politics in the form of secularism has extracted a heavy price and Congress is down to its lowest tally of 44 seats. Identity politics in the form of Hindutva looks triumphant but it too contains the seeds of its own destruction.

No state better illustrates Hindutva’s journey than Gujarat. Once a Congress bastion, the party streaked to a three-fourths majority in 1985 with the Madhavsinh Solanki crafted caste alliance known as KHAM. But zenith was followed by nadir. In the same year Rajiv sacked Solanki as chief minister and Congress was soon consigned to irrelevance. After a period of instability BJP won a clear majority with the support of the Hinduised Patel community and Hindutva took Gujarat’s centrestage. Hindu politics reached its apogee in 2002 with the coming of Narendra Modi and the post-Godhra riots.

After the riots, Hindutva won in 2002 and 2007, but in 2012, let’s face it, Hindutva took a back seat to the reinvented persona of Modi. The footsoldiers of the Ayodhya movement, kar sevaks, VHP and Bajrang Dal lost out in politics. Instead it was a superbly repackaged image of Modi as development guru (and Hindutva icon) who led the saffron juggernaut. If Hindutva was the only consideration for voters VHP’s Pravin Togadia would have been a voters’ delight. But in Gujarat Hindutva takes second place to Moditva.

If playing the Hindu identity meant an easy cakewalk into voters’ hearts, BJP would never lose an election. If simply appeasing the majority is guaranteed to win elections then why does PM Modi even bother to campaign? If identity politics is so all-powerful why was an upstart AAP able to defeat BJP in Delhi? Why did an all-powerful saffron machine come a cropper in Bihar and almost lose in Goa? Importantly, a year after the Babri demolition BJP lost in UP.

Sure, Hindutva in Gujarat and in the rest of India is fast being ‘normalised’. Today Muslims are at their lowest ever representation in Parliament. Gau rakshak attacks on suspected cattle traders across north India have gone largely unpunished, and the patriotism of Muslims is regularly questioned.

Yet even as Hindutva has grown strong, so have its challengers. Three young caste leaders in Gujarat – Jignesh, Alpesh and Hardik – have emerged as a powerful counterpoint to religious politics. Bengal’s didi is fighting Hindutva with her own brand of street power and Hindutva has failed to make a dent in Kerala. Those BJP CMs who repeatedly win elections don’t just play religious politics but are rewarded because they stand forth as champions of ‘vikas’. Mosque demolishers don’t win elections, those who position themselves as administrators – however subliminally Hindu – do. The ‘extreme’ Hindutva faces of 1991 – Uma Bharti, Sakshi Maharaj, Vinay Katiyar – have been slowly marginalised.

Hindutva provides initial momentum, but dissipates over time unless there is a ‘plus’ factor that goes beyond religious polarisation. The canny Indian voter gives identity politics a chance once, maybe twice, but over time turns her back on it if there’s no recognisable delivery of welfare, liberty and justice. When Congress-style secularism became about advancing sectional interests, the voter rejected it.

If Hindutva starts to become only about the identity of a few and becomes an assault on the individual liberties of the many, if the right to speak, dissent, make movies, write books, eat meat, dress, marry, love, or speak a language of one’s choice is threatened, Hindutva too will meet the same fate as ‘secularism’. If BJP falls for the trap of reviving the mandir agitation, it risks alienating those attracted to the aspirational Modi cult. A mosque was demolished for the sake of identity, but identity politics in the long run faces demolition too. No wonder the ghost of the Babri Masjid is having the last laugh.

The article was first published on Times of India written by Sagarika Ghose who is a journalist worked with Times of India, Outlook magazine and The Indian Express. She has been a primetime news anchor and hosts the show ‘Capital View’ on ET Now. At present she is consulting editor, The Times of India. She is the author of two novels, “The Gin Drinkers” and “Blind Faith” both published worldwide by HarperCollins.)