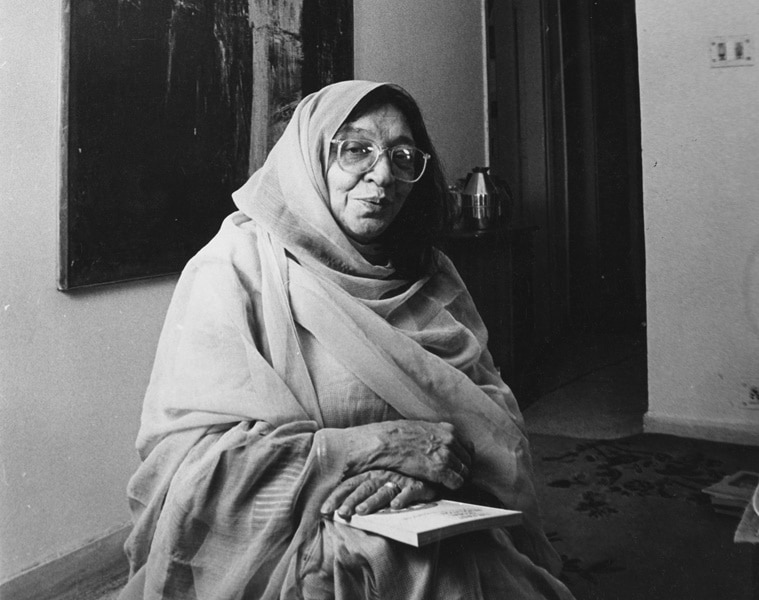

Krishna Sobti, 92, has a new novel out. But the legendary Hindi writer now sees time go by swiftly. In what she calls her “last interview”, Sobti looks back at her childhood, the days of Independence and reflects on the crisis of contemporary India.

My last interview,” she repeats. Her left wrist is pierced with needles, and connected by a tube to a bottle of fluids hanging over the bed.

Four months ago, she turned 92, perhaps the oldest novelist alive in India. Age has done little to dull her creative energies and keep her away from her writerly commitments. Until this stay in hospital, she read three newspapers in the morning, attended protest seminars held by writers, and had almost daily visitors at her home. Recently, her autobiographical novel, Gujarat Pakistan se Gujarat Hindustan, was released. Yet, she is aware of the inevitable and is now “settling pending things” fast. She has just handed over reams of her manuscripts to the archives of a university.

Her husband Shivnath, also a writer and Sahitya Akademi award-winner, passed away a few years ago (both were born on February 18, 1925). Since then, she has lived alone in an east Delhi apartment.

It’s her fifth day in hospital. She is in bed, wearing a blue gown. Her attendant adjusts the bed and elevates it by forty-five degrees. Her face is lined with snow-white wrinkles, her eyes twinkle through her spectacles, and she begins: “Where were we last time?”

Among the most respected Indian writers, Krishna Sobti began with poetry, before switching to fiction. Mitro Marjani, Ae Ladki, Zindaginama (the epic novel got her a Sahitya Akademi award) are considered classics of Hindi literature.

The Hindi critic Madan Soni terms her a “masculine” writer. Her writings often created an uproar for being “obscene”. She even fought a long copyright case with another giant of Indian literature, Amrita Pritam, a case that saw the likes of poet Ashok Vajpeyi and author Khushwant Singh appearing in court to elaborate upon the word zindaginama.

“I don’t believe in ‘women’s literature’. Theorists might analyse texts in this narrow way, but, to me, great texts combine both masculine and feminine elements. ” (Source: Express Archive)

“I don’t believe in ‘women’s literature’. Theorists might analyse texts in this narrow way, but, to me, great texts combine both masculine and feminine elements. ” (Source: Express Archive)

This conversation was held over several visits to her home and, finally, the hospital — during the breaks when she was not under the spell of sleeping pills. Her memory is still sharp. Sobti vividly recalls the horses she rode in her childhood in Gujarat, a small hilly town (now in Pakistan) along the banks of the Chenab, adjoining Kashmir. She remembers her friends, the books she read in her twenties. The impending end looms over her words, as she insists that this interview’s transcript be read out to her. “I am troubling you, but I don’t want any mistake in my last interview,” she says with a laugh, unmindful of the nurse, who has arrived to check her daily medicine chart.

Excerpts from the interview:

You are in your tenth decade. What are your earliest memories?

It’s wonderful to be alive, to go through this significant historical phase of this great country. I have been a witness to four generations. I have seen thousands of sunsets (but fewer sunrises, as I am a late riser!), the many colours of springs and autumns all over this beautiful country, and drenched myself in countless monsoons.

At the time of birth, my linguistic and literary accounts were opened at three different places — my birthplace Gujarat (Pakistan), Shimla and Delhi. My father was a senior civil servant. We alternated between Shimla (then the summer capital) and Delhi, before I went to Lahore for college. Delhi was a village in comparison to Lahore. Teji Bachchan, famous for her performances in Shakespeare’s plays, taught English at Lahore’s Fateh Chand College. The different styles of living and language brought their own limitations and luxuries, and informed and illuminated my writing.

I studied in Shimla’s Lady Irwin School, Nirmal (the Hindi writer Nirmal Verma) was in Harcourt Butler School. He was a year junior to my brother Jagdish, but we barely met.

It was the culture of the British capital, which made even Indians very formal. The city was also divided. Lower Bazaar had an Indian feel to it, the Upper Bazaar on the Mall had a British stamp.

Both Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj were active in Shimla. The former had highly educated individuals, who had the guts to look Britishers in the eye. Hindi was introduced in Shimla by Arya Samaj.

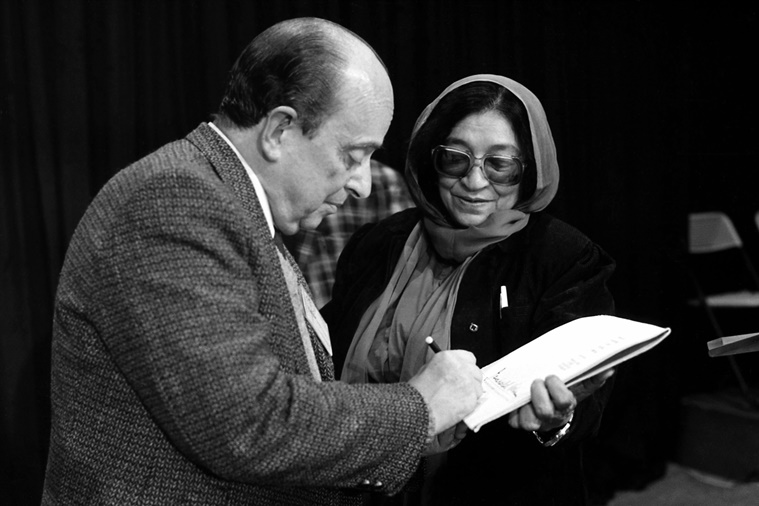

Krishna Sobti with the late Argentine poet Roberto Juarroz during a poetry festival in Bhopal in 1989. (Source: Vijay Rohatgi)

Krishna Sobti with the late Argentine poet Roberto Juarroz during a poetry festival in Bhopal in 1989. (Source: Vijay Rohatgi)

In the 1930s, a Hindi Sahitya Sammelan took place in Shimla. The procession of writers passed through Lower Bazar Road, and not the Mall. When they were walking on the Mall, we showered flowers on them. Suryakant Tripathi Nirala was among the writers in the procession. He looked very impressive, as if he was somebody.

Several Hindi writers of your generation were well-versed in English. Why did you choose Hindi as your creative language?

Many Indian epics, written both by Hindus and Muslims, are in Hindi. Malik Muhammad Jayasi, Tulsidas, Surdas and Kabir wrote in this language. Hindi has a unique dhwani sansar (auditory world), drawn from various dialects. Every word has a distinct sound. The words that have come from Punjabi have a roughness but Rajasthani words carry a unique brevity and rhythm. My creative world carries the memory of various Hindi dialects, Urdu and Sanskrit.

When I was writing my first novel, (Hindi writer) Amrit Lal Nagar told me that this Punjabi-mixed Hindi would not work. I told him to wait for 10 years. When we began writing in Hindi, it was sneered upon, considered a vegetarian language. Nirmal and Phaneeshwar Nath Renu transformed it.

Once, I was in Sweden with (UR) Ananthamurthy for a seminar. Someone asked me about my English translations. I ensure that the silences of my original text remain audible in English, I replied.

What was the scene in the country after Independence?

The Partition was a terrible event. It was difficult to bear the tragedy and the enormous hatred it brought, but we lived through it. It confirms the vitality of this nation that it resurrected itself soon. But the war the present government is fighting against its own citizens now can destroy India.

Independence gave us confidence. I vividly remember the procession down the Raisina Hills on the first Republic Day. Its grandeur was enhanced by the beautiful architectural design of the Lutyens Zone. That generation had a very strong sense of a nation. For at least two generations after Independence, writers were very well read in world literature. We wanted to be the conscience of this nation. Hindi’s creative space increased manifold after Independence.

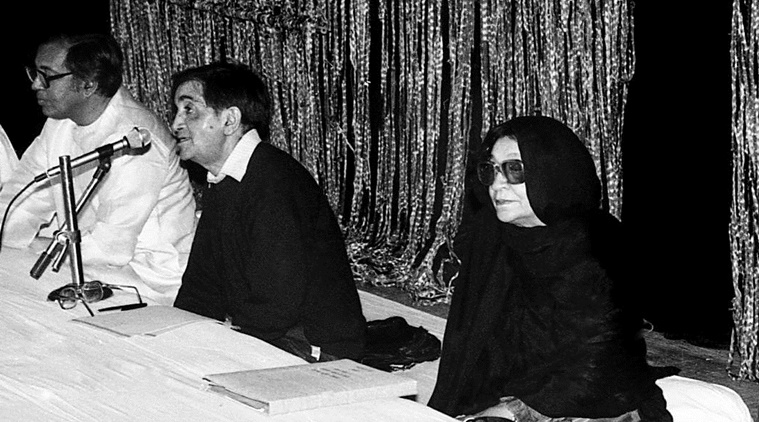

Krishna Sobti with Nirmal Verma (in the middle). (Source: Vijay Rohatgi)

Krishna Sobti with Nirmal Verma (in the middle). (Source: Vijay Rohatgi)

You have created some of the most assertive women characters in Indian literature. Yet, you resist being called a ‘woman writer’. So, what do you mean by the writer as a woman?

My mother Durga was an extremely strong woman, and an excellent horse rider. She was given the most ferocious horses, which she tamed easily . And yet, among the few books she brought with her after marriage included Suhag Raat and Ramni Rahasya (books for women on how to be a consummate lover).

Indian texts have a wonderful concept of ardhanarishwara, a being that comprises both man and woman. It is manifested in my art. Attempting to experiment with this bisexual form, I wrote under a pen-name Hashmat, a male name. I was surprised that besides the texture of my writing, even my handwriting changed when I wrote as Hashmat. The contours of the words that appeared on blank paper were not the same as when they were written by Krishna Sobti. That’s the complexity of art, the joy of being a writer. You become a witness to your own self as it is revealed to you.

I don’t believe in ‘women’s literature’. Theorists might analyse texts in this narrow way, but, to me, great texts combine both masculine and feminine elements. A novel about women does not become less authentic merely because it was written by a man. Recently, at a book fair, someone asked me what it means to be a woman. I replied that I get the same rights from the Constitution as a man does.

When Mitro (the protagonist of the novel Mitro Marjani) uncovers her breasts and stares at herself for long, full of desire, her gaze combines both the male and the female attributes.

To what extent are these women characters autobiographical?

It’s difficult to say. It’s a very complex process. The complexion of writing contains both the internal and external self of the writer. Multiple tensions operate on a text. You cannot draw a line where your self seeps into fiction. Love, sex and death are the defining emotions of this planet. I have always tried to preserve space for them.

What is writing to you?

Writing is a conversation with your self that takes place in language. You capture the sound of your soul, and also the outside noises. I prepare three drafts. As you write the first sentence, you share half of your authority with the text.

I don’t begin with a specific frame. All I have are a few images, ideas and an eagerness to witness them on paper. Writing makes you humble, aware of your limitations.

Writing is an intellectual pursuit, but it’s also creative labour, and a social and political statement. When you write fiction, you handle other characters, and you also become one. There are many books, very well crafted, but they do not have insights because the writer couldn’t transcend herself.

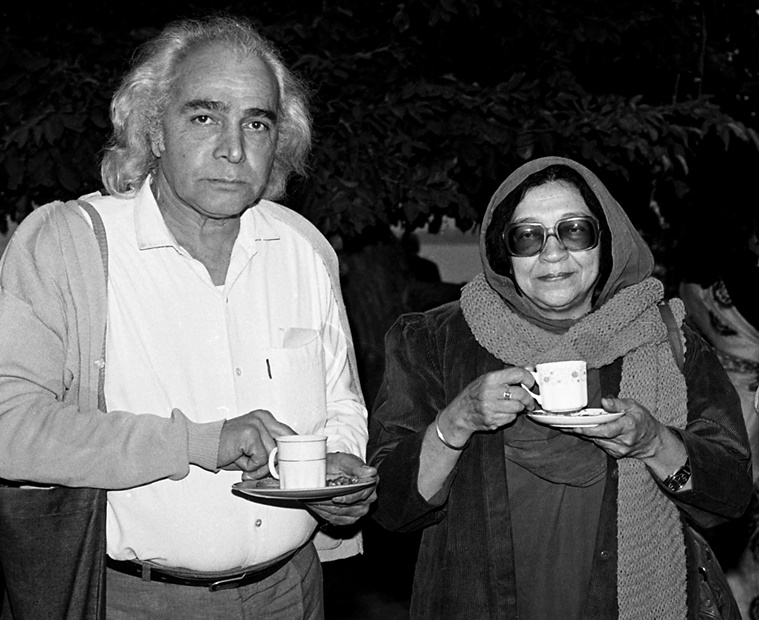

Krishna Sobti with the late Urdu poet Fazal Tabish. (Source: Vijay Rohatgi)

Krishna Sobti with the late Urdu poet Fazal Tabish. (Source: Vijay Rohatgi)

I have very few friends. I am never bored of my company. I write at night — the mysterious silence of darkness illuminated by my solitary table lamp… and I suddenly find words revealing themselves to me in new ragas, rhythms, beats and meanings.

Sometimes, I wish I had learnt painting.

You refused the Padma Bhushan during the UPA government, and recently you returned the Sahitya Akademi fellowship protesting rising intolerance in society. What is your politics as a writer? How do you find the present cultural scene?

It’s frightening. The assaults on creative freedom and the disregard for writers are unprecedented. Perhaps, writers are also to be blamed. For long, they wanted to be seen with the establishment.

For many years after Independence, both the citizens and the establishment were aware of their rights and responsibilities. There was mutual respect, which is now disappearing.

It’s important for a writer to maintain her independence. But the present government is leading the country to a new Partition. They have opened up wounds that were long healed or were gradually getting healed. This nation is an epic text, composed by multiple retellings. It has memories of thousands of years. This government is trying to impose its monolithic narrative on us. You cannot even argue with them as they have no understanding of our culture.

Once, I went to Tunisia (a Muslim-dominated country in Africa). A Tunisian girl said that she wanted to offer me a dessert — and she ordered halwa. What we consider a Hindi word, actually, has an Islamic origin. That’s the linguistic culture of our nation.

It’s our duty as writers to contest their claim on our history. There is a history that lies in archives, but there is a bigger narrative that vibrates in the soul of this nation. That narrative has to be saved.

Four Writers and a Friendship

Three writers who frequently figured in our conversation are Krishna Baldev Vaid, Nirmal Verma and Swadesh Deepak. Verma died in 2005. Having attempted suicide on a couple of occasions, Deepak “disappeared” over a decade ago. There is no official confirmation of his death. “He is not on this planet,” Sobti says, recalling that “he always carried an alcohol bottle with him”. Vaid, who turns 90 in July, lives with his daughters in Texas.

Verma and Sobti studied in Shimla in their childhood. Their debates over their works, sometimes bitter, often come up in her conversation. Once over a drink, he called her writing a “myth”, and she, in turn, reminded him of “those 20 sentences” he had “picked up from Czechoslovakian novels”. Yet, she quickly adds: “His presence had an altogether different meaning … it was an immensely creative presence.” “Jaldi chala gaya (He left too early),” she says, a rare occasion when her eyes moisten. “I was thinking of him just yesterday.”

Like her, Vaid also studied in a Lahore college before Independence. Sobti’s husband Shivnath was a year senior to Vaid in the same college. She, though, would meet Shivnath only decades later. Her files contain several letters KB (that’s what she calls Krishna Baldev Vaid) wrote to her. Some letters are from the US, where he completed his PhD on Henry James from Harvard University and later taught at several universities. Both also have a joint work to their credit — Vaid Sobti Samvad, a book comprising their long conversation over various issues.

There is little chance that Vaid will return to India. But she is somehow convinced that he will. “Ek baar KB se bheint zaroor hogi (We will certainly meet, at least once).”

Her Major Works

Mitro Marjani (1966): A woman, married in a joint family of three brothers, asserts her sexuality and unabashedly scolds her husband for not fulfilling her sexual desires. She mouths expletives and is often seen taking a stand on family issues concerning justice and morality. At first, publishers rejected the novella. Once it was released, the work stunned the Hindi world.

Zindaginama (1979): Her most ambitious work, widely considered an epic novel. It won the Sahitya Akademi award, making her the first woman Hindi writer to get this honour. It is the story of a rural village in Punjab. A rambling narrative spanning across decades, it incorporates several dialects of Hindi, which makes it a unique literary text. Sobti wrote the first draft in her 20s, and even sent it for publication, but withdrew its copies, having found that the publisher had changed several words. She kept the manuscript with herself before its revised version was eventually published nearly three decades later.

Ae Ladki (1991): A poignant conversation between a dying old woman and her daughter. In this novella, they talk about life, death, and the place of marriage and love in a woman’s life.

Hum Hashmat: Writing under a male pseudonym, she sketched vivid profiles of her contemporary writers in three volumes, written over 15 years. The texture of this work — the first volume was in 1977 — is remarkably different from her other works.