By Hasan Ghias

The darkest hour is just before the dawn”, says an old English proverb. Are we living through our darkest hour since the foundation of our republic? Perhaps yes; perhaps not. The worst may still be in store, or we may have hit rock bottom. Nobody knows.

Three distinct climacterics characterize the trajectory of Indian Muslim history since the nineteenth century, one occurring in each of the three centuries. While we can trawl through the pages of history, and its multiple narratives, to draw our own lessons and conclusions about the first two, it is the third event that poses complex challenges that we have to grapple with and find our way forward through numerous snares and confounding developments to discover opportunity in adversity.

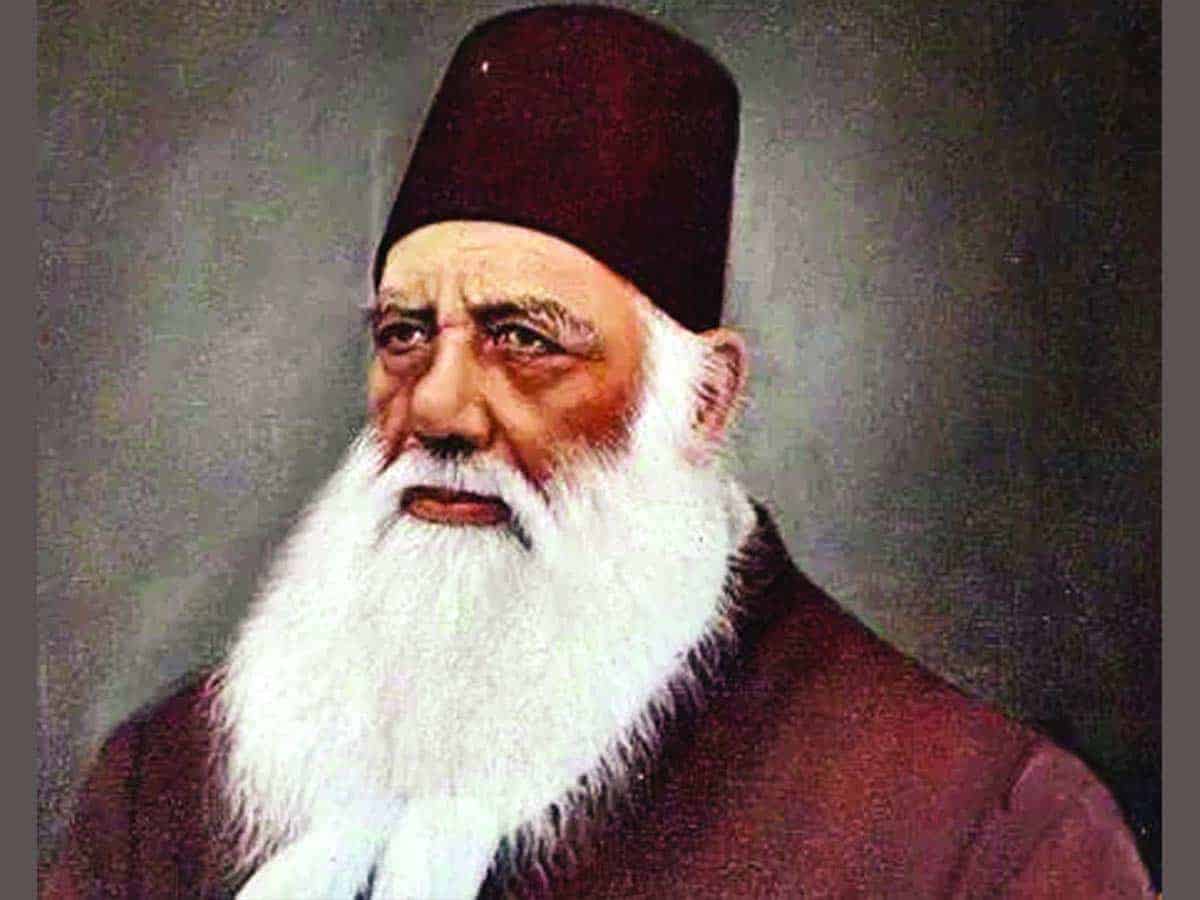

The end of Mughal rule was accompanied by the catastrophic consequences of the rebellion of 1857. Pulverized by merciless reprisals, the Muslims of India were in a state of pitiable turmoil. Emotionally charged responses, ranging from meek submission to defiant rage, resulted in enormous confusion but little direction. It was against this backdrop that the great pragmatic visionary, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, picked up the fragments of the dashed hopes and destroyed morale of his community to piece together a cogent and reasoned response and a blueprint for revival. The Aligarh Movement was born and played a historic role in shaping the destiny of Muslims in the colonial state and thereafter.

The second cataclysmic event in the history of post- Mughal India, with consequences for Indian Muslims more abject and dire than those that followed the great rebellion, was the tragic partition of India. Confused, directionless, suffering from loss of self-esteem, devastated by violence against their lives and property and relentless attacks on their identity, the Indian Muslim community yet again searched for direction. For decades, fed on deceptive promises and imbued with false hopes, far from seeing their aspirations realized, they were silent witnesses to their relentless marginalization that pushed them down to the bottom of the socio-economic ladder. This time no Sir Syed appeared to provide a reasoned and cogent response. Even the wise sage, Maulana Azad, whose predictions proved prescient and prophetic as the community hurtled down the route to disaster, found it beyond his tired capacity to weld together the hapless Muslims who chose to stay. In any event, he did not live long enough to see the pathetic picture fully emerge.

Just as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries witnessed major turning points in the lives and fortunes of the Muslims of India, the twenty first century saw its own watershed moment in May 2014. The political order changed dramatically, perhaps irrevocably. The general election results were understandably received with trepidation by the Muslims and the promise of ‘sabka sath, sabka vikas’ was perceived with some scepticism. Worse was yet to unfold. The stunning victory of the BJP, which fielded not a single Muslim candidate in the Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections of 2017, confirmed their political irrelevance in India’s most populous state. The potent and poisonous canard of Muslim appeasement conveniently glossed over the fact that while Muslims constitute 19% of the population of Uttar Pradesh, their representation in the administration, judiciary, police, provincial constabulary, and the public sector falls woefully short. During the 2019 parliamentary elections, the ugly face of brute majoritarianism was on full display. The BJP swept to power with an even bigger majority than in 2014.

The sustained disempowerment and marginalization of Muslims in independent India gathered fresh momentum in 2014 and snowballed in 2019. Even as the economy was suffering from the double whammy of demonetization and a clumsily enforced GST, high on the legislative agenda of the re-elected government was triple talaaq. Never mind that the Supreme Court had already declared the practice invalid; it was still very important to punish with imprisonment a crime that never happened. That done, what next? Kashmir of course. How handy the old chestnut of Article 370! Substantially hollowed out anyway, why not deliver it a death blow, particularly when approbation is assured? Along with Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, out goes Article 35A that restricts the right to own real estate in Kashmir to residents of the State. Several other states of the Indian Union have similar protections, but a Muslim-majority state is an anachronism, so it’s demographics must be changed. There are several instances where Union Territories in India have been elevated to the status of states, but Kashmir is the sole example in the history of independent India when a full-fledged state has been degraded to two Union Territories.

Curtailing the rights of a few million Kashmiris is a walk in the park when compared with the gigantic task of disenfranchising countless more Muslims in the rest of India. Is this possibly the purpose of the combination of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens? When you take away their citizenship, you also rob them of their dignity, their property, their livelihood and, of course, their vote. The government seems to have learnt little from the NRC experience in Assam. Almost two million people, mostly the poorest of the poor, more than half of whom are Hindus, have been declared illegal at enormous cost. How many tens of millions will meet the same fate in a nationwide exercise? How many detention centers will be needed to house them, how will they be fed, what will the total cost to the exchequer be of this massive undertaking? What will be the administrative complexity of this mammoth exercise and its accompanying risks, including bias, bribery, mischief and misclassification? Yet the government seems not to have discarded this controversial plan. From among the unfortunate ones left out of the National Register of Citizens, many of those who are not Muslim will be let off the hook thanks to the provisions of the Citizenship Amendment Act. Those who are Muslim, classified as termites, will be left to languish in concentration camps, helpless, hopeless and stateless. And while this broth is simmering in the cauldron, why not sprinkle a bit of seasoning by throwing a spanner into the idyllic lives of sixty five thousand inhabitants of Lakshadweep islands, 95% of whom are Muslims.

Where then lie the hopes for a new dawn? Within ourselves, of course! Abandoned by most, shunned by many, we, the new untouchables, must prove our worth upon our own touchstone. We have to cut our own path with hardy perseverance, indomitable will and unflinching faith. We have to build stretch into our lives and embed determination in our thoughts. On a tight rope between despair and hope, we must keep our balance and fix our gaze. The chips may be down and times may be tough, but every adversity creates new opportunities. Every cloud has a silver lining.

A good place to begin is within. This is a moment for introspection, deep and unsparing. Recognition of a malaise is a prerequisite for remedy. Our moral fiber, which is the very essence of our being and our faith, is in a state of disrepair. Unless we can restore our values and regain our moral compass, we cannot prepare the ground for regeneration. Decades of neglect have compounded our problems, whether social, educational, economic or political to an extent that they now seem extremely daunting. To reverse this trend of interminable decline, we must learn to pull together. Social cohesion is a consequence of either internal forces that bind or externally applied pressure. In the absence of strong internal bonds, external pressure could facilitate social cohesion, provided the community has the strength and resolve not to crumble under its impact.

As a first step, we must learn to deal with the predators within who feed off the capital of the community for their personal gains. Our inability to leverage the wealth of the Waqf assets to serve their intended purpose by freeing them from the jaws of sharks is too well known to bear repetition. We must also be wary of Muslim politicians who pretend to run with the hare, but are in reality hunting with the hounds, or of those who compete for crumbs from the table of privilege at the cost of those whom they represent.

The route to regeneration is via education. The madrasas can serve a useful purpose of educating a substantial, underprivileged section of the community by making their curricula more relevant to contemporary needs. What prevents this from happening- a lack of imagination, resources or will? What about our schools and institutions of higher learning and how do they compare with institutions run by a much smaller minority- the Christians? We can take pages from their playbook and improve our educational institutions. We cannot have good education without good teachers. What kind of facilities do we have for training teachers? Teaching is more than just a profession; it is a mission and those engaged in it must pursue it with missionary zeal. Are we able and willing to step up to the plate?

We may be educationally weak, but our artisans excel in their crafts. A myriad of them toil away with negligible bargaining power, while most of the profit in the value chain is appropriated by middle men. Surely these matchless skills can be leveraged to produce greater rewards for those who create things of such beauty.

Education is important; livelihood generation an imperative. Jobs are scarce and will remain so in the foreseeable future. Yet, in entrepreneurship, the limit is only what our imagination imposes. The majority of the Indian Muslim population lives at the bottom of the economic pyramid. This base is not barren. Opportunities abound for micro-businesses to serve segments of the population that big business does not serve adequately and the government neglects. Social enterprises could provide guidance and resources, including finance, to these micro-businesses helping to generate employment and income.

“Ranj se khugar hua insaan toe mit jaata hai ranj,

Mushkilein mujh par padi itni ke aasaan ho gayein”.

Ghalib

The din of divisive politics seems to have, at last, woken up the community. You can feel the churning, the stirrings and the desire for change. Nothing concentrates the mind more than an existential threat and Indian Muslims are responding to this challenge. Over two millennia ago, the Jewish Rabbi Hillel said “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And being only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?” Tired of relying upon false props, they are looking to be self-reliant. They are expressing in no uncertain terms their loyalty to the Indian nation, its constitution and its flag. They know that it is now or never. They cannot be wished away and they will not make themselves invisible. They are citizens, not termites, and they cannot be held accountable for the real or imagined excesses of the past. They belong to the soil of India and to it do they return. They may be down, but they are not out. They are not willing to fall away from the margins of Indian society and polity and are determined to play their role in nation building as equal partners in progress. They will rise and shine and usher in a new dawn:

“Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments

By narrow domestic walls

Where words come out from the depth of truth

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way

Into the dreary desert sand of dead habit

Where the mind is led forward by Thee

Into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake”.

Rabindranath Tagore

Hope never dies.

Hasan Ghias is a US-based Business & Organization Development Consultant who writes regularly, among other subjects, on the country of his origin, India.