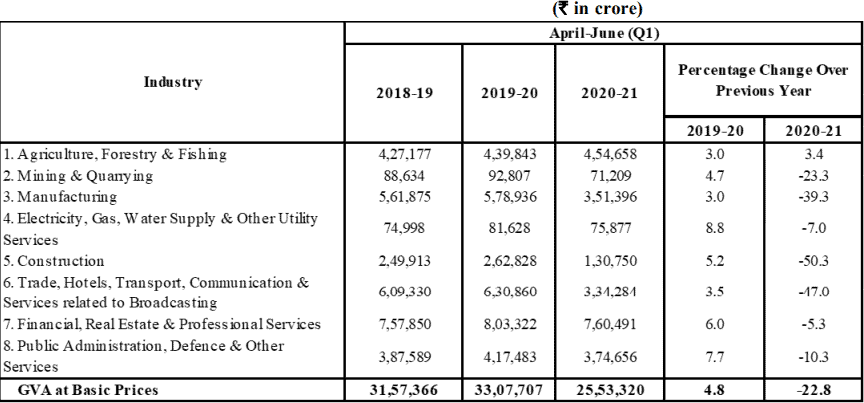

Hyderabad: As a result of the COVID-induced lockdown, Indian economy shrank by a massive 23.9 per cent in the April-June quarter of 2020-21, the data from the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI) read. Further, in terms of gross value added (GVA), GDP plummeted 22.8 per cent compared to last year. The contraction, which is the biggest ever on record, is however not unprecedented.

This is also the first recorded contraction since the government started releasing the gross domestic product figures in 1997-98.

Is this a recession?

Recession is a period of temporary economic decline marked by a slowdown in industrial activity and trade, generally identified by a gross domestic product (GDP) contraction in two straight quarters.

So, India, technically, has not yet entered a recession. But weak investment, capital spending and consumption demand will keep negatively impacting the economy. It means the chances of contraction are high in the subsequent quarter, which will push India into recession.

“Two quarters of negative growth amounts to recession, and there certainly has been negative growth in the June and September quarters,” said former finance secretary Subhash Chandra Garg, quoting a leading newspaper.

Subsequent quarterly announcements will also reveal if contraction will be worse than the current one. That’s because data collection too was affected due to the pandemic. “With a view to containing the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, restrictions were imposed on the economic activities not deemed essential, as also on the movement of people from 25 March 2020. In these circumstances, the usual data sources were substituted by alternatives like GST, interactions with professional bodies, etc. and which were clearly limited,” Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation (MoSPI) said.

Recessions in the past

So far, India has had five instances of real GDP contraction since 1947. The contractions in 1957-58 (-1.2%), 1965-66 (-2.6%), 1966-67 (-0.1%), 1972-73 (-0.6%) and 1979-80 (-5.2%) were far behind compared to the current fall. The reason was the same each time—a monsoon shock that hit agriculture. With the farm sector accounting for the dominant share of GDP and given weak external balances, most recessions were earlier driven by severe droughts or high international energy prices.

Interestingly, this time around, agriculture is the only sector in the April-June quarter to have shown positive growth.

The impact of COVID-19

Even before the pandemic struck, Asia’s third-largest economy was in the midst of a slowdown as a crisis in the shadow bank sector hurt new loans and took a toll on consumption, which accounts for some 60% of India’s GDP.

The business closures, job losses and salary cuts resulting from the pandemic gave a deadly blow to consumption with lower incomes translating to less spending. In its annual report released on August 25, the RBI noted that “the upticks [in consumption] that became visible in May and June after the lockdown was eased appear to have lost strength in July and August, mainly due to the re-imposition or stricter imposition of lockdowns.” It highlighted that the shock to consumption was severe, suggesting that ‘the contraction in economic activity would likely be prolonged into the second quarter.’

It also noted that consumer confidence fell to an all-time low in July, with a majority of respondents of a survey reporting pessimism over the general economic situation, employment, inflation and income. This is visible in consumption data; there has been an all-round dip in demand for goods and services.

Way out?

While it is almost certain India will slip into recession, economists are now trying to figure out when will India come out of it. RBI, in its annual report, pitched for deep-seated and wide-ranging reforms to get back on the path of sustainable growth.

The economic situation is made worse by limited fiscal support, leaving the onus on the central bank to provide the bulk of the stimulus. The RBI has cut interest rates by 115 basis points so far this year, boosted liquidity and transferred billions of rupees in dividends to the government.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) had recently predicted in its report that India’s economy is expected to rebound in 2021 with a robust six per cent growth.

However, the World Bank, in India Development Update-2020 Report, cautioned that credit risks play out as firms and households find it more difficult to service their interest and repayment obligations in a slowing economy.

Chief Economic Adviser K V Subramanian, while giving a statement on the latest GDP figures said, “The number is on expected lines, the global economy has taken a hit, India is not isolated. India is seeing a V-shaped recovery, agriculture has seen an uptick and it will continue to do so.”