By Ajaz Ashraf

New Delhi: Stories from the past began to haunt me as I hopped from one devastated mosque to another in north-east Delhi, where mobs killed and looted with impunity for well over 48 hours in late February.

I remembered how the Taliban used explosives to blow up, in March 2001, two giant-size statues of Gautam Buddha in the Bamyan Valley, Afghanistan. It justified the demolition of these 6th-century statues of Buddha on the ground that Islam forbade idolatory.

I also recalled the Islamic State deploying bulldozers and explosives to devastate archaeological sites as they swept their way through north Iraq and Syria. For instance, they reduced to rubble the 1,900-year-old Temple of Baalshamin in Palmyra, Syria. They blew up a mosque in Mosul where Prophet Yunus—Jonah to Christians—is said to be buried. The Islamic State was opposed to the veneration of prophets and saints.

These stories began to play on my mind as another journalist and I, with the help of two locals, began tracking down 16 mosques officially listed as having been attacked and damaged in the riots.

We made our way, sometimes along narrow lanes deep within neighbourhoods, to nine of them—and then I just gave up.

One is a unique number, an exception; two, a little less so; as the toll rises, whether of violent deaths or smashed mosques, it becomes progressively harder to rationalise the numbers.

All you can do, in the end, is to ascribe them to a world-view, one that teaches people to hate whatever they think is the “out-group”. This was what drove the Taliban and the Islamic State’s barbarous iconoclasm, and this is, equally, what lies behind the targeting of mosques in north-east Delhi.

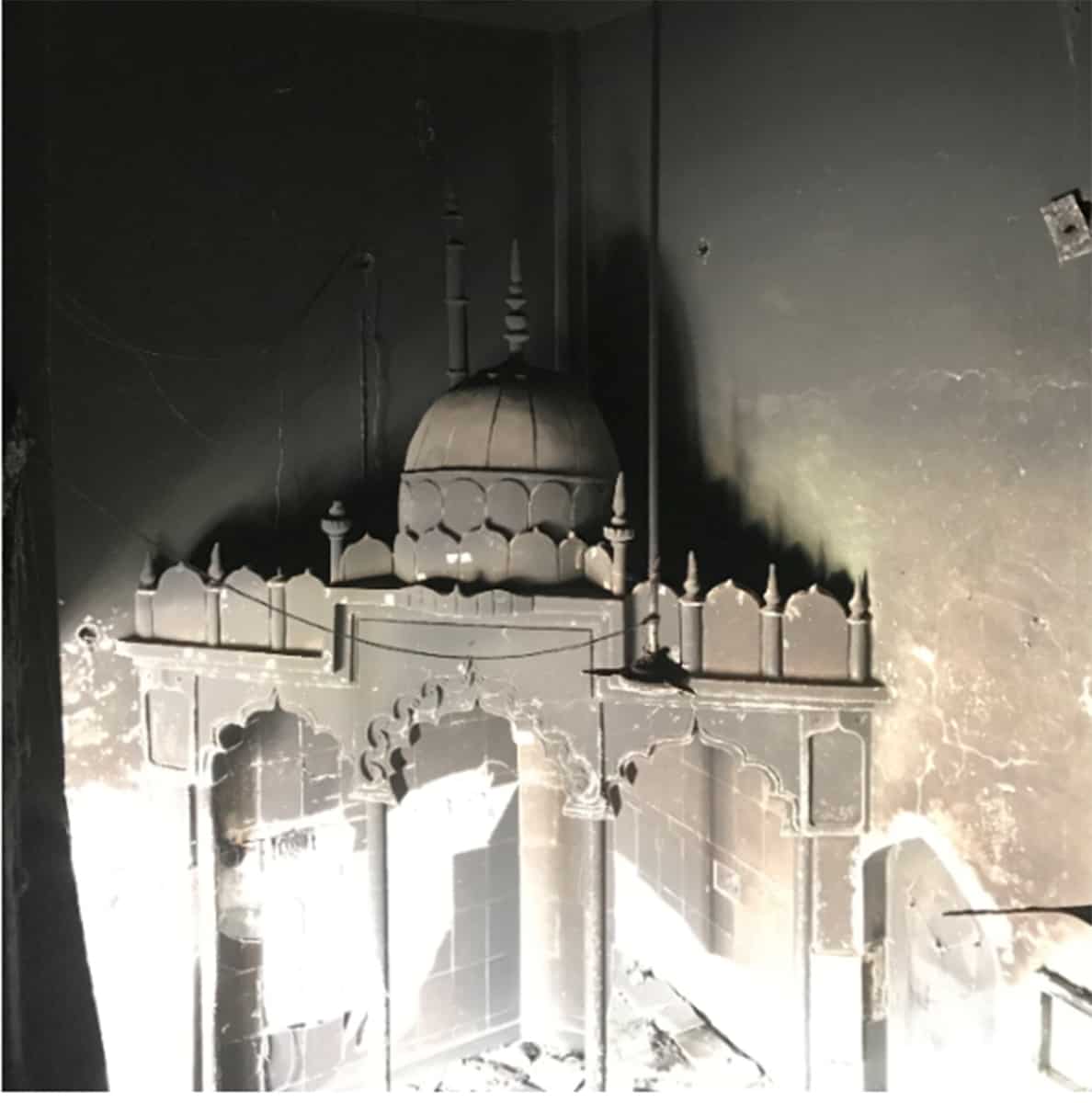

The stories of the attacks on these mosques were chillingly repetitive—hordes of hoodlums, wearing helmets, armed with rods and lathis, and chanting Jai Shri Ram, broke into the sacred spaces of Muslims. They smashed windows, set carpets and mats afire, tore the Quran and religious books, ripped out donation boxes, and tossed gas cylinders to trigger explosions powerful enough to scoop out marble floors.

These mosques do not have an ancient past, nor are they architectural marvels. Yet the fury the mobs vented on them was Taliban-esque in nature. They showed their extreme contempt for sacred spaces that were not theirs; made it clear, in fact that others’ places of worship belonged to the realm of the profane.

Are the sights in north-east Delhi intimations of the future that awaits India? Perhaps the only way to avoid that conclusion, if you make a pilgrimage to these broken mosques, is to keep the Tayyaba Masjid, in Shiv Vihar, which hugs Karawal Nagar, as your last stop. It will keep your sanity intact.

THE SAVIOUR

When Naushad Akhtar, the Imam of Tayyaba Masjid, heard a din late on the night of 24 February, he immediately called up Sunil Prajapati to say that rioting had begun. Akhtar had once been a tenant of the 34-year-old Prajapati, who is in the business of selling biryani. “I told him it must be a marriage procession,” recalled Prajapati, who fondly calls Akhtar jijaji.

However, when Prajapati went to the terrace of his house, he saw that shops on the main road were ablaze. He and some others decided to stand guard at the alley where Muslims lived. They kept the mob at bay.

At 2.30 pm on 25 February, around 300 attackers in helmets, their faces masked, burst into the alley through another route and took to breaking the mosque’s doors. Akhtar said 60 Muslims, including 15 women and 20 children, had taken refuge inside the mosque. They all ran up the stairwell to the third-floor terrace and locked the door behind them. By then, the assailants had begun searching the premises, floor by floor, until they reached the flight of stairs to the roof.

When Akhtar called Prajapati to say, “We will die”, he and two other residents of the colony—Chandrapal and Sandeep—rushed to the mosque and bounded up the stairwell. There were heated exchanges, jostling and pushing. The attackers taunted Prajapati for taking the side of Muslims.

“I told them that Imam Akhtar is my jijaji. You will have to kill me before you can touch him,” Prajapati recalled. “I told them that those who destroy temples and mosques are only capable of killing people.”

Almost miraculously, Prajapati was able to bargain with a mob. The assailants agreed to give safe passage to the Imam and others, who were then escorted by Prajapati and his friends to Loni.

The masjid, however, was set on fire, which was later extinguished. The assailants, however, returned on 26 February, and set it ablaze again. On the day we visited the Tayyaba Masjid, the alley had an eerie feel about it. There was no one around. Houses had been burnt and looted.

“Hindus and Muslims have a very good relationship in this mohalla,” Prajapati told me. “The attackers were all outsiders.” That may be the case, but is all really well in the neighbourhood? “Some do taunt me for saving Muslims,” he said.

THE BETRAYAL

When we entered Gali No. 29 of C Block, Khajuri Khas, it was crowded with Muslims examining houses, their inner walls pitch dark with soot. A team of NGOs was, on the Delhi government’s behalf, helping the riot-hit fill forms to claim compensation.

A little inside the alley is the Fatima Masjid, which came under attack on the morning of 25 February, as did the entire lane. The attackers began by pelting stones and then switched to hurling petrol bombs. Muslims residents said they fled to the terraces of their houses, hoping for police assistance, which arrived many hours later.

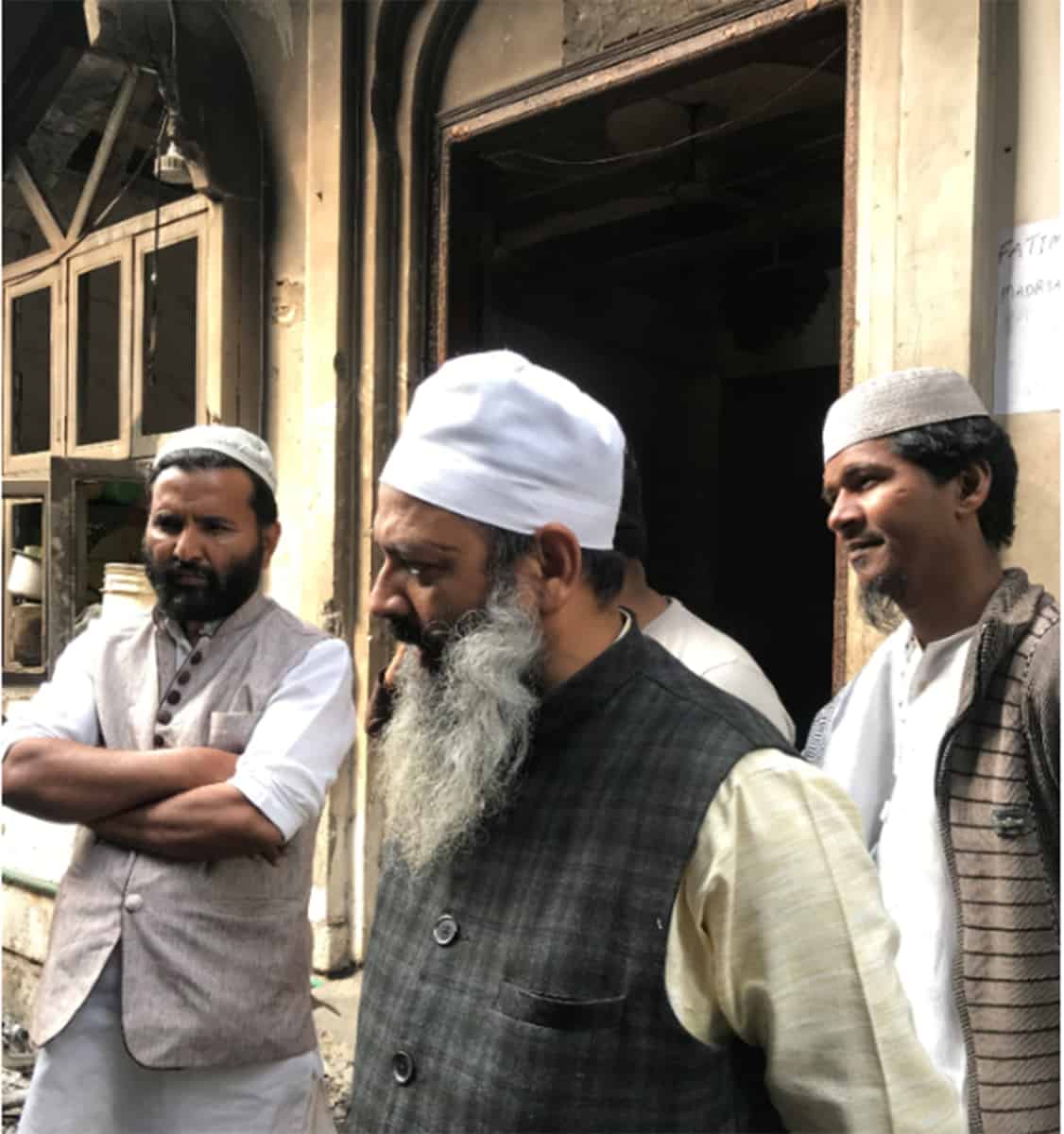

Mahboob Alam, the general secretary of the Fatima Masjid’s committee, stood outside the masjid, its interiors as dark as the inside of an oven. He said that on 24 February, as the tension in the area mounted, Muslim residents had wanted to evacuate to a safe place, but were dissuaded by their Hindu neighbours.

“They assured us that they would fight along with us if things went wrong,” Alam said, tousling his beard. “On 25 February, we pleaded with them to come to our rescue. They did not.”

Perhaps the mob scared them?

“Scared?” he repeated my question, his voice rising. Pointing to a Hindu’s house near the masjid and taking his name aloud, Alam said, “When they ran out of gas cylinders to explode in the masjid, he supplied them a couple.”

Did he and others plan never to return to Gali No. 29? I asked.

“We have to return. Where else can we go,” he said. A moment later, he understood what I was driving at. “Do you mean I should not publicly accuse him of betrayal?”

I did not know what to tell him.

BATTERED AND BURNT

The Faruqiya Jama Masjid is spread over 1,000 sq yards of land. Behind the mosque is the Jamiatul Huda Madrasa, a two-storey structure with a third floor under construction. On the evening I visited the complex, its gates were closed. An NGO team had come to examine the damage. I looked through a window, its shutters and grills missing, at ravaged interiors.

According to Haji Faqruddin, the president of the Jamiatul Huda, the mosque came under attack around 6.30 pm on 25 February, when the mandatory part of namaz had just got over. The assailants swooped down on men coming out of the mosque. They were battered mercilessly.

“Mohd Zakir and Mohd Mehtab died on the spot; Areeb, an 18-year-old alumnus of the madrasa, was in a coma for days and died recently. Mufti Tahir, the mosque’s imam, Jalaluddin, the muezzin, and Haji Abbas, with multiple fractures, are in hospital,” Faqruddin said.

The assailants returned the next day, at 8 am. They attacked the madrasa, burnt all documents, smashed the CCTV cameras, and looted the money in the donation boxes.

BOMBED OUT

At 8.30 pm on 25 February, Maulana Zahid, the imam of the Madeena Masjid, in Shiv Vihar, called up Mohammad Dilshad, the mosque’s president, to inform him that a mob, chanting Jai Sri Ram, was closing in on the colony. Dilshad advised him to get out quickly.

“He locked the door of the mosque, and escaped through interconnected alleys to Mustafabad [a predominantly Muslim quarter]. He would not have survived otherwise,” said Dilshad, taking us around the mosque.

It made for a grim picture—smashed-up windows, torn pages of religious books, including the Quran, strewn around, twisted fan blades, liquor bottles in which the assailants must have carried inflammable liquid, and scraps of gas cylinders lying around.

As the assailants attacked the Madeena Masjid, a breakaway group headed towards the Auliya Masjid, around 300 meters away, located on the Nalla Road. On their way, they set houses on fire and tossed gas cylinders into them. The ground-floor ceiling of one house had collapsed but for a portion on which lay a double-bed. It could well have been a picture from a war zone.

“We ran away, taking with us the mosque’s imam, Qari Irfan,” said Gulsher Ahmed, the president of the Auliya Masjid. Barging into the mosque, the mob seemed to have made a bonfire of books and prayer mats, and tossed three cylinders, which did not explode. Nevertheless, the damage is extensive. I was taken, in pitch darkness, to the first floor for inspection. When I came down and stepped outside, I saw my right palm covered in soot. I had, presumably, held the wall for support to climb the stairs.

“I do not spend the night in Shiv Vihar,” Ahmed said.

TALKS OF RECONCILIATION

Unable to break open the door of Meena Masjid, in Bhagirathi Vihar, the assailants, on 25 February, wrenched out the grills of two windows and threw burning tyres inside. The damage here is minimal. Mats cover the floor. You would not think the mosque was attacked.

Haji Shamsuddin, the president of the mosque, said that the Hindus and Muslims have been sitting together to plan out the future. “No doubt, the attackers were from outside. But the mistake of our Hindu neighbours was that they did not try to argue and stop the mob from attacking us.” Shamsuddin said.

In Ashok Nagar, Jitendra Sharma and two other Hindus tried to remonstrate with the assailants as they mounted an attack on the Jama Masjid, also known as Maula Baksh Masjid. “They pelted Sharma’s house with stones,” said Mohd Arif, whom we tracked down by using the phone number on the official list. “The Hindus have promised us to help us repair the mosque,” Arif said. “They assure us that such an attack will not happen again.”

The Jama Masjid presents as dismal a picture as most of the other devastated mosques. It was raided twice. In the first round, the mosque was pelted with stones and shops on its premises were set on fire. After a Hindu neighbour summoned a police force, which evacuated the Muslims living in the neighbourhood, the mob broke into the mosque. They took away the money in the donation box, tore down the Quran, set the carpets and mats on fire, and broke the water pipeline.

THE TOURIST SPOT

The Tyre Market Ki Masjid is not your typical mosque, with domes and minarets. It is a space covered by asbestos sheets mounted on iron poles, with its three sides not even walled. It is hard to destroy where nothing exists. That must be the only reason it has sustained little damage. Located on the main Wazirabad Road, the tyre market was set ablaze. Nothing remains other than mangled heaps of shops and merchandise.

On the afternoon we arrived at the Tyre Market, two paramilitary personnel were on guard. The mosque’s entrance was cordoned off. Near the barrier, children as well as adults stood around, capturing on their mobiles, and laughing and chatting all the while, a forlorn mosque and desolation around it.

A NEW BEGINNING

Remember the viral video of the attack on the Chand Baba Ka Mazaar? Yet, it is not listed on the official list of mosques attacked and damaged in the riots. We stopped to examine the mausoleum, a nondescript, at best, 10 feet by eight feet structure. A part of the wall adjoining one of the entrance gates, from where an assailant was captured on video tossing a petrol bomb, was broken.

When we visited, the mausoleum had opened for the first time after the riots. Hawkers sat around with baskets of flowers. Minhaj Pehelwan, the gaddi nashin or spiritual heir, accused the police of helping goondas attack the mazaar.

Those trooping in to pay their respects or pray at the mazaar were mostly Hindus. “Yes, far more Hindus than Muslims patronise the mazaar,” Pehelwan said.

That was ironical, to say the least. Even when their co-religionists treat this space as sacred, the Taliban-esque mobs saw it as profane. This is the only possible explanation for their attack on the Chand Baba Ka Mazaar.

As we left, opting not to visit more desecrated mosques, I reflected on what Prajapati, the saviour, had said to a mob: “Those who break temples and mosques are only capable of killing people.” A chill ran through my bones. I tried to tell myself that the coordinated attack on mosques in north-east Delhi were not the first of their kind in our history.

There are, after all, documented stories of places of worship destroyed in medieval times. But for this to happen in 2020 in the capital city of the world’s largest democracy feels like the beginning of something dreadful.

The author is a journalist. The views are personal.