Fifty (50) is an important milestone in a man’s life. Though seemingly it doesn’t make much difference as the sun outside is the same and people around me are as cheerful or sad as before depending on how one looks at life, 50 does mark a point to ponder.

Seated at a beautiful bungalow overlooking a hilly landscape covered in flaming read bougainvillea plants and tall palm trees at hilly Lonavala, I muse on life’s journey.

Given that I was born a sickly child, my parents said, it was a miracle that I survived. Jisko Allah rakhe, usko kaun chakhe (The one whom God protects, is not felled by others) is how my mother would describe my survival.

Half a century ago, rural Bihar was so backward that pucca road was a rarity, health services were utterly poor and education in doldrums. Customarily mothers gave birth at their parents’ places (maika) and local midwives helped in deliveries. So it was not uncommon that, unlike my own children, I was not born at a hospital. That reminds me of a strange thing that happened in my second daughter’s birth certificate. Her birth certificate issued by the municipal corporation carries the name of the hospital where she was born at as place of birth, instead of the area or locality we live at. But in rural areas half a century ago the valid birthday was the day that was entered in your school register. And so it happened with me. Only your parents knew when you were born. And my father, a high school teacher, kept dates of birth of his children in a diary. The diary showed 17.1.1971 as my birthday.

One of the advantages of growing up in a joint family is that you learn to share things quickly. Growing up amidst an elder brother and an elder cousin, several uncles and aunts, grandparents, it was a secured childhood. Never lonely and showered with bountiful love and affection, I grew up with much confidence despite carrying a deformity. Deformity?

Yes, I was born with cleft lip. Children with cleft lip are taunted as khona or khonma. It really hurt me whenever someone called me khonma or khona because I had a cleft lip. My parents didn’t want me to carry this “deformity” which was a source of “taunts” and “jokes” eternally. I must have been around 10 when my parents took me to a surgeon in the district headquarters, Darbhanga, for corrective surgery of my cleft lip. The surgery was successful even if it was not perfect. Unlike the protagonist in the acclaimed film Smile Pinki, I was not a very poor child. My friend and then colleague Anubha Sawhney who too had undergone the surgery for lip correction wanted to do a personal piece after Smile Pinki became a smash hit. She asked me if I felt embarrassed by carrying a scar on my face. I told her it was after a very long time that someone had reminded me that I once carried cleft lip.

Though the surgery could have been better–the lip is not joined perfectly–it removed the “stigma” of being a khona forever. It helped restore my confidence, my “completeness” as a boy, as a man. It “normalised” me as it removed the “abnormality” that I carried.

Since the upper lip remained cut in early years, the gap allowed many of my teeth to grow unhesitatingly and haphazardly. They jumbled and protruded, giving a sort of “unpleasant” look.

People with protruding teeth have few takers in the marriage “market”. I grew up with them even if barbs and “unhealthy comments” like dantul or dotla were often directed at me. My father had neither the means nor information to get my teeth in order in the teenage. A few marriage proposals failed to materialise into wedding because of my “ugly” look thanks to the protruding teeth. I remember a shooting pain entering my soul when brother of a “suitable girl” broached this subject and “regretted” that my parents had failed to get my teeth in symmetry in time. That coarse comment hit like an arrow and I cancelled marriage with that girl. Mercifully the girl I finally married never protested nor did she complain against my scarred lip or protruded teeth. “Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder,” goes the cliche. And looks can be deceptive too.

There was a time when one gentleman, a very noble heart, wanted to help me undergo dentistry correction. It didn’t take me long to find that he also had a daughter to marry off. Never one to depend on somebody’s charity, I neither married his daughter nor accepted his benevolence.

Years later, after I settled into my job and saved from my earnings, I listened to the advice of my good dentist friend Dr Maroof Reza. He suggested I allow him to do some “cosmetic dentistry” with my teeth. It took a week or so for the procedure and my protruding teeth were either removed or shortened and shaped in an order. And while all this happened, my wife was away in her maika (parents’ place). With my new set of teeth, I appeared before my wife. She of course loved it. But the happiest person to see me in a sort of new facial avatar was my father. I saw a beatific smile play on his face. Perhaps he was amazed at the scientific advancement. Perhaps he was happy at I gaining a better smile by virtue of a new set of teeth.

These are cosmetic changes. But today at 50 when greetings from friends and acquaintances fill my inbox, I remember my departed parents. How they nursed a sickly child with little chances of survival to health. How they ensured that my cleft lip was corrected through a surgery so that I was saved from “shame and embarrassment”. I am grateful to my dentist friend who removed the stigma of dantul forever. If life is the name of unending battles, I am ready to take them on. There have been many disappointing moments in the journey so far but there have been far more good moments too. Blessings outweigh the curses on life’s scale.

Is it not God’s grace that I survived debilitating illnesses in my childhood? Is it not a divine blessing that I defeated the dreaded COVID-19 in the cursed 2020? Is it not mercy of my maker that I enjoy love and affection of so many friends? How do you define happiness? It is about being happy with what you have and not regret for what you don’t have. Materials bring happiness but there is a limit to it. I have seen many seemingly wealthy persons ruing their fate. Why? Because material possessions alone don’t guarantee happiness. I am happy when I see children laugh, elders appreciate and admire my little efforts to make others happy. To give you don’t need to own an empire. To give you need a kind heart. I am grateful to God for giving that little kindness in my heart.

As I enter 51st year, I seek continued blessings of friends, divine mercies that can keep me doing whatever little work of kindness I can do. Goodbye till I return with next write-up.

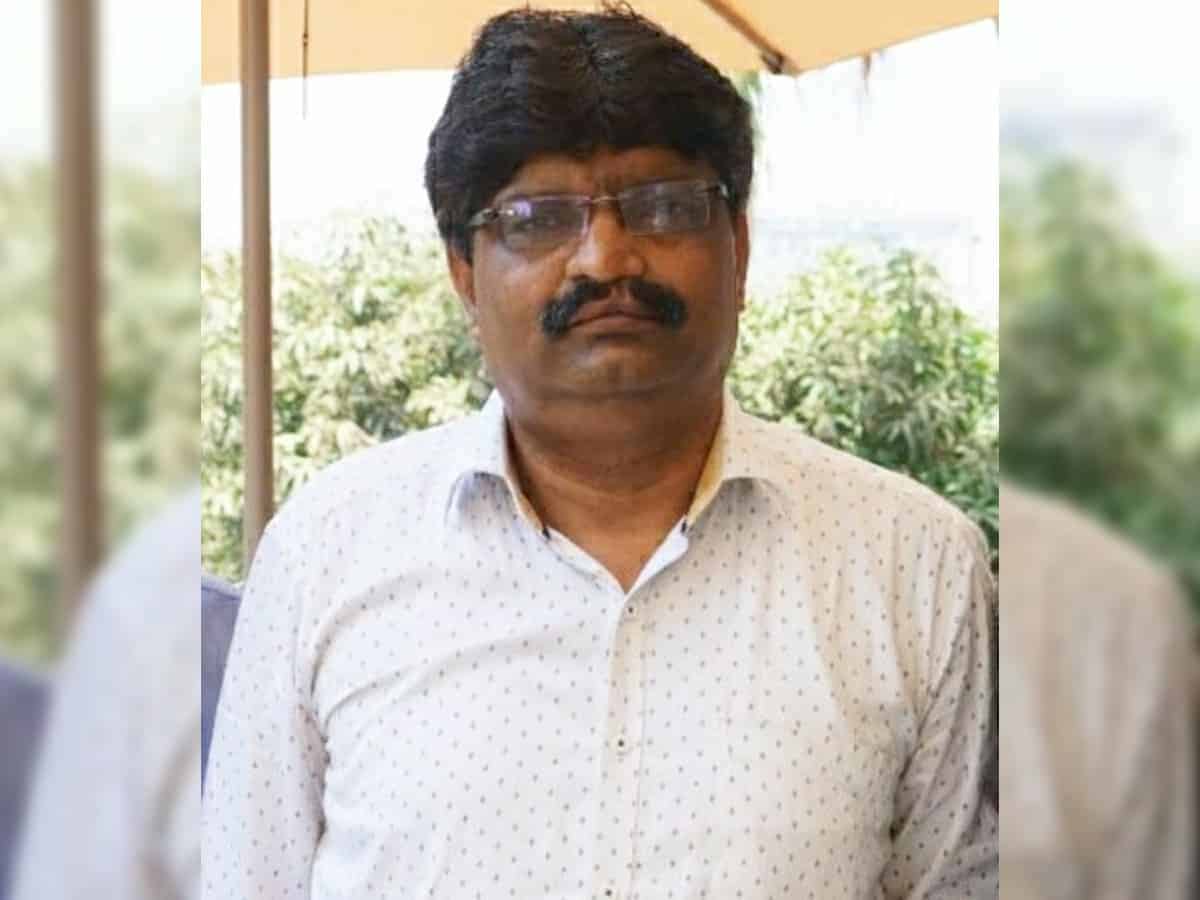

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog.