I didn’t join my parents and siblings in their train journey on a

breezy March morning (March 26, 1942) to Hyderabad, because I had to participate in a youth camp in a far corner of the country. But from the unedited accounts my brothers later gave me I could fabricate a picture of their travel to and arrival in what looked like a different country.

My parents and siblings had made the journey to Hyderabad, our first

immigration destination, by a passenger train that stopped at every

station helping them excitedly write down the name of every station

between Rayanapadu and Secunderabad from where they took a shambling meter gauge train to Kacheguda, a suburb of Hyderabad city.

The station was no match to our Bezwada railway station in either

size, number of platforms or number of transiting trains, they later

told me, pride shining their faces. Yet the station was a marvel of

eye-catching architectural majesty and elegance. A fusion of Indo-Saracenic and Asaf Jahi schools. On the middle of its roof was a

clock tower with a dome that reminded you of the helmet-like headgear the Nizam used to wear.. The station had a flourishing circular garden in front of it and a tonga lot to its right and a customs house on its left. Though their bags passed through the Customs net, they were not asked to show their passports.

Thus they landed in the territory of His Exalted Highness Rustam-i-Dauran, Arustu-i-Zaman, Wal Mamaluk, Asaf Jah VII, Muzaffar ul-Mamaluk, Nizam ul-Mulk, Nizam ud-Daula, Nawab Mir Sir Osman ‘Ali Khan Siddqi Bahadur, Sipah Salar, Fateh Jang, the Nizam of Hyderabad, enough titles to crush a person under their weight.

Next to the tonga lot was an ordnance depot, a symbol of British

hegemony. Today, this depot, the tonga lot, the circular garden have

their existence in hearsay. You could also see a live steel locomotive

resurrected from a bygone age and mounted on a circular cement

platform in front of the station.

When I joined my parents and siblings after returning from the youth

camp I found people in this foreign capital spoke a different

language; wore different clothes. All big houses, including key

government offices were shrouded off behind high walls with an Arab

armed guard in traditional garb sporting a Janbia (half-sword) tied around his waist, sitting on a stool as a sentry at the entrance. They are known as Chaush, Arabs the Nizams had brought from Yemen. They were harmless people, we learnt later, but scared children for fun.

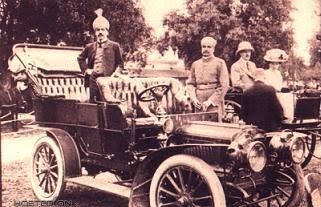

When Mirza Ismail became the Prime Minister for a brief period he

pulled down the high walls of government offices and replaced the

compound wall on the Tank Bund that shut off the view of the

waterscape with a railing. Of interest to us were the cars of the

Nizam’s hospitality department known as Amera – the Rolls Royce,

the Bentleys, the Daimlers, the Humbers, the Rovers, Rileys, MGs,

Wolselys etc. The unostentatious Nizam himself used an old-fashioned convertible for travel in the city.

My father had rented two flats, part of a four-flat apartment in

Barkatpura, the best address in the city at that time with the Nizam’s

ministers and secretaries as our neighbors. In front of it is a

beautiful circular garden doubling as a traffic island. The very

residence of these dignitaries assured security for the entire

district.

The kingdom had its own postal system, its own railway and road

networks and an efficient public sector, the envy of the British ruled

region. In his dominion, the Nizam had the giant Singareni coalmine,

the Bodhan Sugar Factory, Sirpur Paper Mills, Sirpur Silk Factory and the Praga Tools. The big Nizamsagar project, the several small dams built across the Musi, its own mint, postal services and an

impressive railroad network, an efficient road transport

administration, the Public Gardens in the city, with a zoo attached to

it. Under the Nizam the city had the highest mileage off cement roads

in the country.

The kingdom had own citizenship identity called Mulki and a Fasli (introduced by the Mughal King Akbar) calendar. Some also believed it to be Islamic calendar showing Friday as the weekend. Education, from primary to university levels in Urdu, made the kingdom a real island. The language polarized the people into people speaking (Bollywood actor) Mehmood style Urdu and those speaking the language of Anjuman-e-Taraqui Urdu. It also built a wall around Urdu graduates who couldn’t get a job or college seat outside Hyderabad.

Our acculturation began with buying a copy of Bolta Khaida, a Urdu

primer, and practised the script by reading display boards. We also

began wearing pajamas at home and using flip-flops inside the house.

We started listening to Hindustani classical music, soon graduating to

host mehfils.

Freshly arrived as peregrines we set out to explore the geographic and

historical landmarks of the city. On a Sunday morning my uncle hired a tonga to see the great Charminar famous for cigarettes named after it, only competitor to W.D. & H.O. Wills. A ten cigarettes pack outside cost one anna but at Charminar you got 16 cigarettes for one anna.

We rode through wide roads and a river of bicycles. Getting out of the

tonga we stood dwarfed and awestruck before the magnificent masonry edifice, a civil engineering marvel of the fifteenth century, the city sentinel. Charminar which is a mute spectator to Royal Romance, court conspiracies, calamities like the 1908 floods and the recurring plague epidemic and, the most important of all,

is the seismic power upheaval in 1948 that ended an era of Asaf Jahi

rule and inaugurated a democratic regime.

Hyderabad is a city where history is impounded like it is in Delhi.

Every grey beard living south of the Musi River has a swatch of

history passed on to him by a greyer forebear. Charminar is a metaphor for Hyderabad, a matrix from where both its political and cultural life emanated. The Great Makkah Masjid (Mosque) and its vicinity make an enclave of architectural wealth and Koranic fervor. The great structure is older and taller than the Taj Mahal built on a foundation of romance and love for a woman.

Here we stood before this Jewel of Hyderabad. It seemed to demand

genuflection from spectators, architects, tourists, civil engineers,

artists, writers, from the birds overflying it, the pigeons fluttering

around it singing its paeans, from historians and from everything that

calls itself human. A collapse of belief occurs in its presence.

The city’s demographic canvas was an interesting quilt, consisting

mostly of Muslims in the Old City across Chaderghat pul, and to the

North of Musi river lived Telugus, Kannadigas, Maharashtrians and

other linguistic communities. As a result of predominantly Muslim

cultural milieu, they seemed very different from their counterparts

living in the Indian Territory.

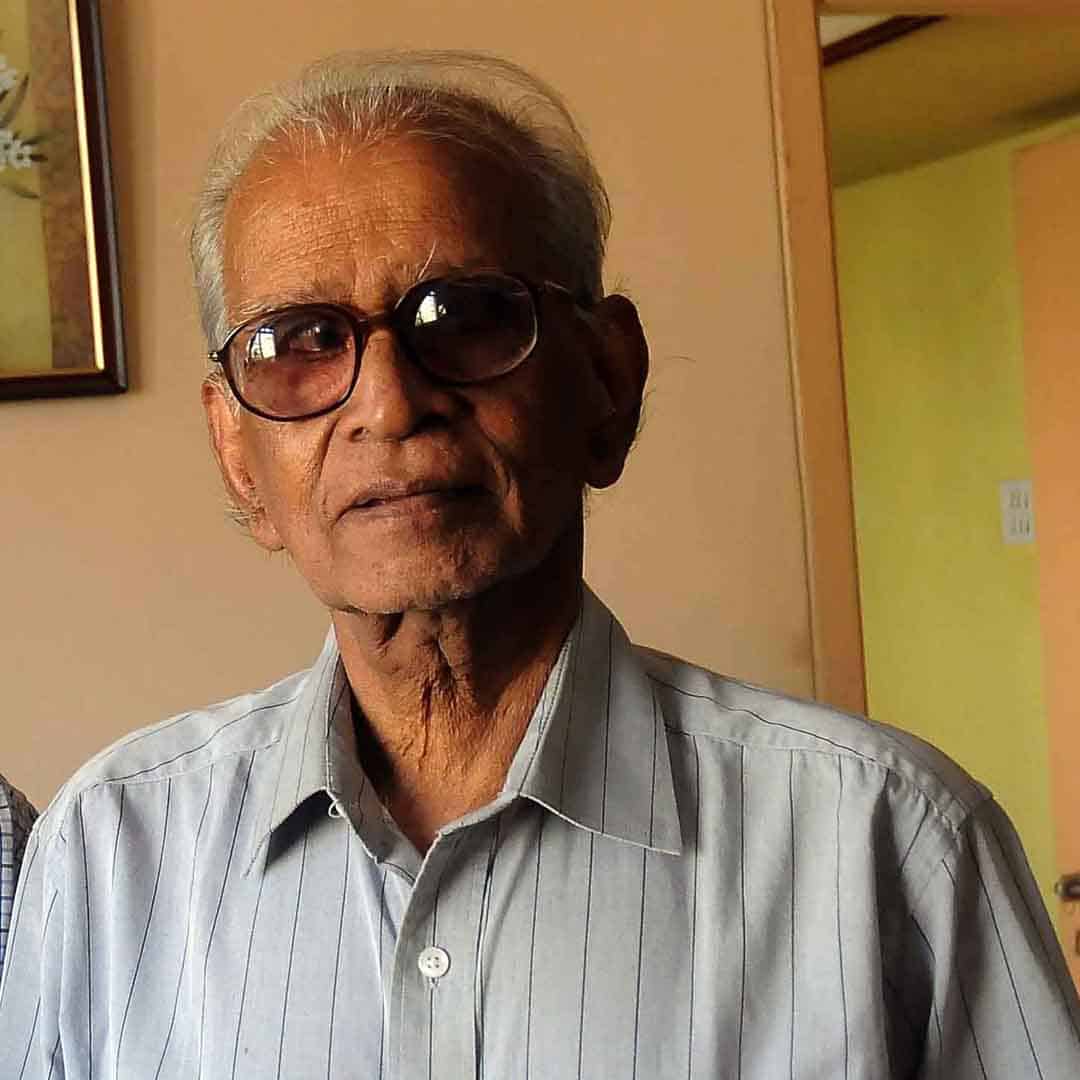

*Dasu Krishnamoorty (born 1926) is a veteran journalist, writer and journalism teacher. He belonged to the first batch of students of Osmania University journalism department (1954), served on the desk of The Sentinel, The Daily News, Indian Express (10 years), Times of India, Patriot (20 years), taught at Indian Institute of Mass Communication, University of Hyderabad, Osmania University. After moving to New Jersey in 2001, Krishnamoorty turned to literature, compiling two anthologies of short stories by Telugu novelists and authored autobiography (The Seaside Bride and other Stories) in 2019 at the age of 93.