Daneesh Majid

Hyderabad: A A Hussain & Books, once a prominent fixture in the Abids area, held a special place in the hearts of Hyderabadis as well as book-loving visitors to the city. Just a few years ago though, it vanished from the horizons of the city.

Sadly, digitization, online retailers, and bookworms who instantly took to both spelled the demise of not only this legendary bookseller. The death knell was also tolled for the flagship branch of Walden.

These bookstores were once bastions for the city’s literary souls.

Although big corporate chains like Crossword and Landmark are getting by, the same cannot be said about the shops that sell books in Urdu — a language that once held sway in the government, education and literary landscapes of Hyderabad.

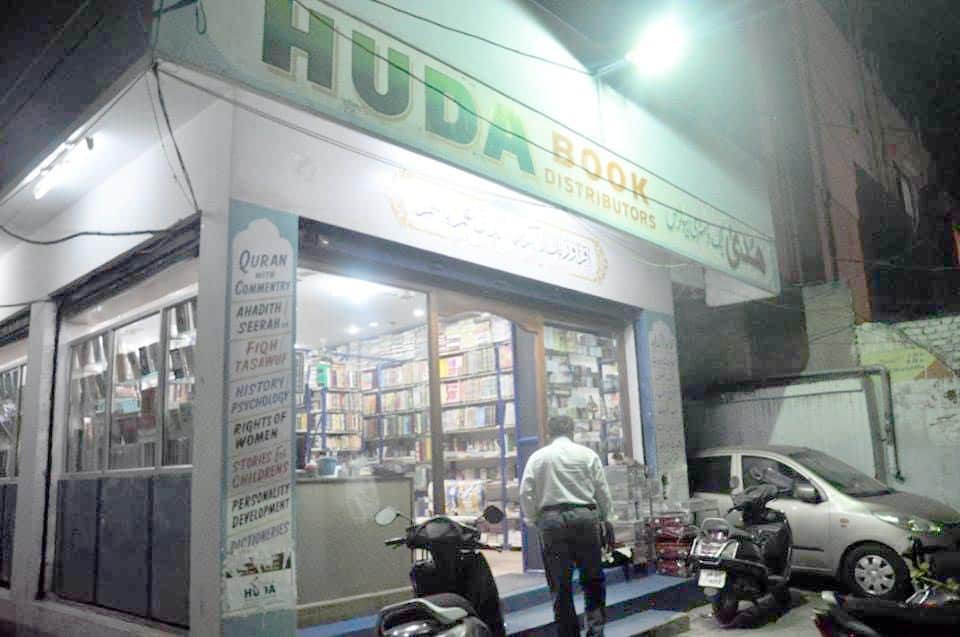

Upon entering the literature section of Huda Book Distributors in Chatta Bazaar, Old City, one can surmise that Urdu prose and poetry just aren’t worth the money for Hyderabadis. In this chamber, there now stands a worktable laden with files and a computer. Just about a month ago though, Urdu titles hovered over the heads of readers from two huge shelves in the space occupied by this worktable.

Ever since the store opened up in 2000, it was always a sheer joy for Huda owner Basit Shakeel to figure out what books to recommend for customers just based on brief conversations with them. Despite receiving a modicum of patronage much before it became Telangana’s second language (on paper); Urdu did have its ardent literary enthusiasts.

However, that seems like another age with digital platforms today diminishing books and attention spans. Already on the wane, Urdu literature’s excruciatingly slow demise has become even more painful.

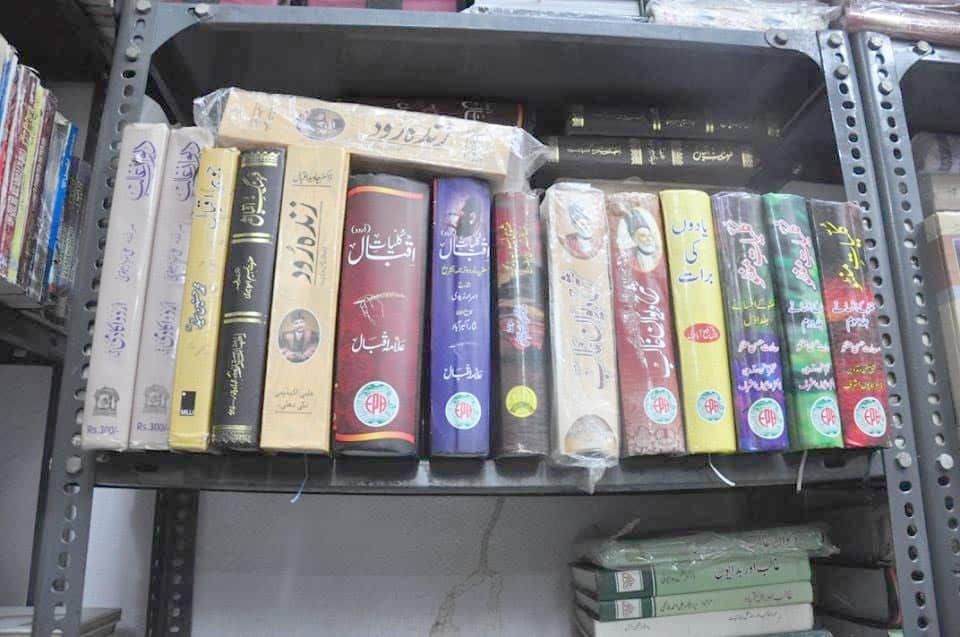

“At first, the adbi (literary) and deeni (religious) books used to be sold on the premises of the main store,” recalls Shakeel. He adds, “Yet with people preferring the digital book in English rather than the physical Urdu ones, I relegated the adbi titles to a room on the side.” The books that used to adorn those two shelves have either been sent back to Delhi or stored in a warehouse for one reason only.

People aren’t exactly eager to buy them.

That too, when English translations of legendary Urdu authors like Saadat Hasan Manto, Ismat Chughtai, and Quratulain Hyder are available via online and retail outlets. People who enjoy these English versions haven’t necessarily disowned the physical book. Instead, they are literary savvy individuals who consume these prolific authors’ works in a language that helps put food on the table of many families.

Rahim Khan, a veteran member of Urdu Hall at Himayat Nagar, attributes the apathy towards Urdu literature to the dwindling numbers of Urdu-medium schools whose decline commenced in the early 1960s-1970s.

“An inferiority complex afflicted the Urdu-medium educated folks. Consequently, many parents began sending their kids to English-medium schools. Already a hangover from the colonial days, not knowing English was a sign of inferior status,” remembers Khan.

Such connotations even removed traces of Urdu script, not just in schools, but in households as well.

Khan adds, “The downfall of Urdu readership over the past six decades has been so gradual that it has been hard to measure.” The statistical declines throughout these years were just too minor to notice.

The fact that the language is perceived as an exoticized specimen at elite cultural festivals or a language taught only at madrassas doesn’t really help either.

According to one Huda employee, only once in a month does a reader who prefers to buy an Urdu book come to shop for non-religious books. With these titles not flying off the shelves into readers’ hands, space also becomes an issue.

Shakeel conjures up a time when renowned humor writer Mujtaba Hussain asked him to sell his then newly released works. “It is only because of his reputation that I could sell them on fast track. Otherwise, the movement of books is too slow,” he specifies.

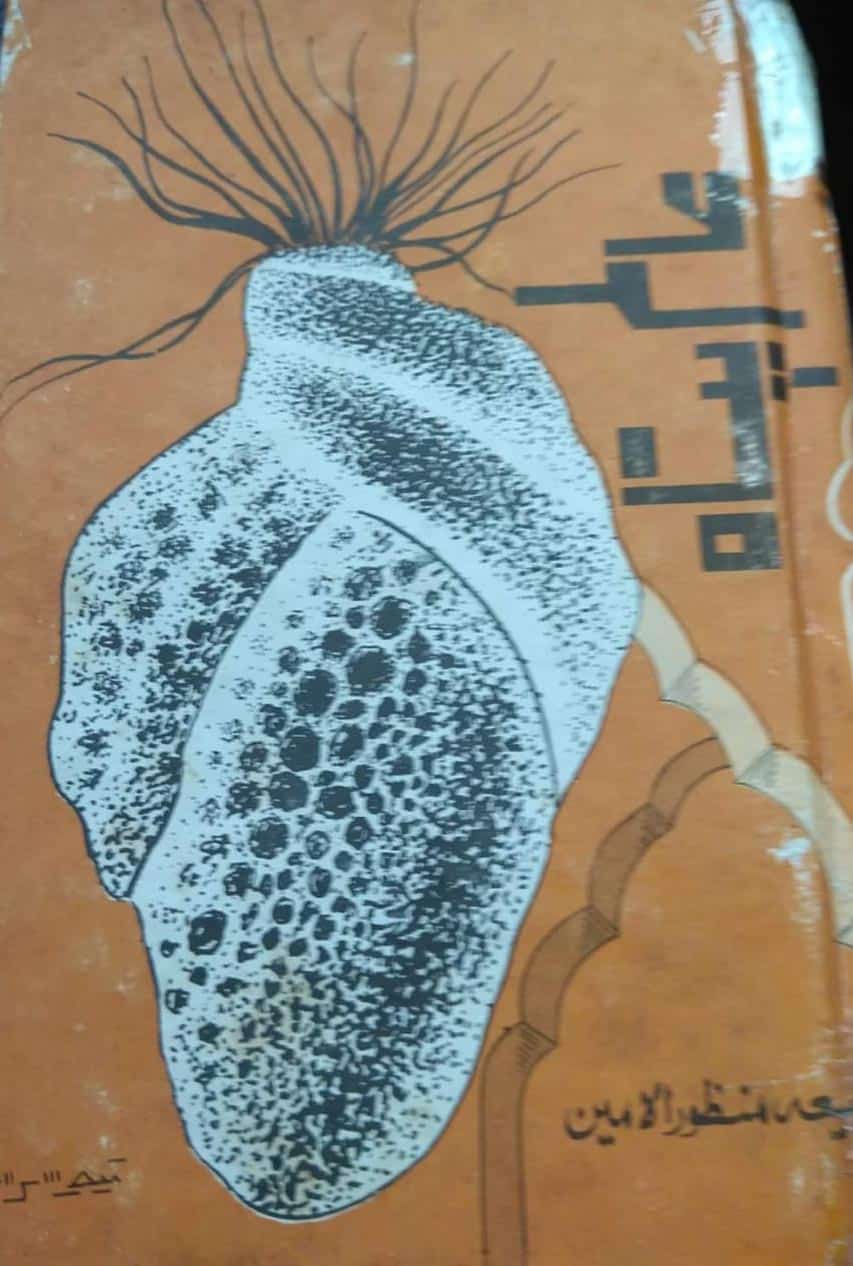

Besides Hussain, Hyderabad is home to other eminent litterateurs like Jeelani Bano and Rafia Manzurul Amin. Unfortunately, due to this lack of space one will rarely find the latter’s classic, Alampanaah, at certain outlets.

***

Alampanaah, was a bestseller which celebrities like Shabana Azmi and ordinary literary buffs picked up from Husami Book Depot. Nestled behind the dilapidated brown arches on Patherghatti Road alongside a strip of jewelry emporiums, restaurants and apparel outlets is this bookstore from the last Nizam’s days.

Hamid, a salesman at Husami mentions, “We have many copies in our warehouse but rarely does someone come to even ask for it.”

Interestingly enough, Amin’s masterpiece is available online for a mere Rs. 150, but only in the Hindi script. Despite supplanting Nastaliq script, Devanagri has made Urdu literature somewhat more accessible to youth and elders alike who instead read Hindi. Hindi, as well as English transliterations via Rekhta.org, have also found an audience among young readers.

Commenting on the irony regarding the demand for this gem of a novel in the language that it was actually written in, Hamid states, “The last person to ask for Alampanaah wasn’t a native of the author’s soil which we also hail from.”

“Instead, it was an American linguist who learned the language from scratch,” he laughs.

Since 40 to 50 percent of the sales from Delhi books are used to cover the logistical expenses, the book depots prefer to keep those on display in the hope that their revenue will pay for the transportation costs. Hence, the inexpensively produced self-published titles are mostly relegated to the warehouse.

Books from Pakistan are expensive as they are even costlier to bring in. Although following the Pulwama attacks in February this year, no titles have been coming in from there. However, be it local or imported books, Hamid points out to a bitter truth that to a lesser extent applies to English literature too. He elaborates, “People won’t think twice before spending Rs. 2,000 on a fancy accessory or clothes at Shopper’s Stop but will balk at the thought of buying a Rs. 200 book.”

“Even if they do pick up a book, they will ask for a giant 40 percent discount. 10 percent – 20 percent isn’t unreasonable though,” he deplores.

Revenue from Islamic books on jurisprudence, commentaries, and history keep Urdu bookstores afloat. So do orders from the Urdu-medium Maulana Azad National Urdu University and Urdu departments at various institutions of higher learning as well.

Therefore, one will not find many Urdu bookshops that carry literary titles just as much as they do religious ones.

Of course, those who consume deeni material aren’t immune to the bargaining bug.

***

According to Nizamuddin, the owner of a landmark Old Delhi Urdu bookstore, Kutb Khana-e-Anjuman-e-Taraqqi Urdu, there is a type of devotion that Urdu lovers exhibit whether they are from a place where the language has already died or is dying.

He calls it “murda-parasti (devotion to the dead).”

When Walden closed its shutters for the last time just a few months ago, city folks lamented the loss of their favorite venue for books, shopping and general family outings.

After all, it is easier to eloquently eulogize a bookstore rather than to financially patronize it.

Is it only a matter of time before frugal customers and non-(Urdu) readers ensure that Hyderabad’s remaining few Urdu bookstores meet the same fate as A A Hussain and Walden?