The explosions in the Sayed-ul-Shuhada high school in western Kabul about two weeks ago killed over 60 people while more than 150 were injured. Most of the victims were young girls, aged 13 to 18 years, who were attending the afternoon shift of the school that catered exclusively to the Shia Hazara community in Afghanistan. The Afghan Taliban’s condemnation of the attack was, to my mind, plausible though their claim that it was the handiwork of the militant Islamic State group working in con cert with the Afghan government was clearly an attempt to hold the government responsible and perhaps understandable as a riposte to the government’s claim that the Taliban were responsible.

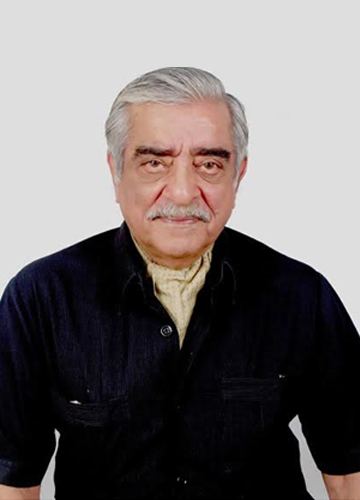

This was said in a column written by Najmuddin A. Shaikh, a former senior servant of Pakistan’s Foreign Service in Dawn, perhaps the oldest and prestigious English language newspaper of Pakistan.

He wrote that while the Taliban did not carry out this attack there is no doubt that given their Deobandi and Salafi beliefs they regard the Hazaras as heretics. What is even more tragic is that not just the Taliban but every ethnic or religious community in Afghanistan perceives the Hazaras in the same way.

The Hazaras constitute around nine per cent of the Afghan population though some claim a much larger percentage. They are theoretically descendants of the Changez Khan Mongols who settled in Afghanistan during the Mongol forays into South Asia. From the start, however, it seems that they had a lowly status and up to the 19th century, they could be sold and bought as slaves. Their persecution was particularly bad dur ing the reign in Kabul of Amir Abdur Rehman who ruled from 1880 to 1901. He is better known for having negotiated the agreement with the British to demarcate and recognise the Durand Line as the border between Afghanistan and British India. The Hazaras could no longer be slaves but their status was that of serfs condemned to perform only menial tasks.

The New York Times in reporting on the school attack talked of it as “a foreshadowing of what is to come” meaning the deterioration of the security situation. This is unfortunately true but even more important is the fact that to all Afghans, be they Pakhtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Turkmen or Baloch, the Hazaras deserve no better.

For the Taliban, this general Afghan contempt for the Hazaras is compounded many times by the role the Hazaras played in partnership with Uzbek opponents of Gen Rashid Dostum in 1997 massacring the Taliban trapped in Mazar-i-Sharif after their abortive effort to take over the city. More than 5,000 Taliban died, mostly at the hands of the forces of Hizb-i-Wahdat, the Hazara political and military party. It is unlikely but even if there is some sort of reconciliation between the Taliban and other Afghan parties, the Hazaras cannot expect to escape the revenge the Taliban, who have long memories, will take.

The Hazaras, before Pakistan was hit by the disease of sectarianism had a comfortable position in this country. Gen Musa, a proud Hazara, could write about rising from jawan to commander-in-chief. Then the situation changed. The Taliban refused to surrender Riaz Basra of the Sipah-i-Sahaba when his location in Afghanistan was conveyed to them, being ready, it seemed, to cock a snook at Pakistan, the only country that was supporting them internationally. From Riaz Basra’s Sipah-i-Sahaba have emerged the Lashkar-i-Jhangvi and other extremist organisations whose avowed goal is the elimination of the Shia who they regard as kafirs. As a result, in Pakistan, according to a 2019 report by Pakistan’s National Commission for Human Rights, at least 509 Hazara have been murdered for their faith since 2013.

The prospects attacks are limited for Hazaras

The Human Rights Commission Pakistan says that from 2009 to 2014, nearly 1,000 Hazaras died in sectarian violence while thousands were injured. To curb attacks on the 600,000 Hazaras living in the towns of Mariabad and Hazara Town in Quetta, the authorities have built military checkpoints, road blocks and walls around the areas. This has not stopped the attacks by such organisations as the Lashkar-i-Jhangvi.

Other Afghans, tired of the strife in their country, try to escape abroad but for no other ethnic group in Afghanistan or Pakistan is this more urgent than for the Hazaras. The prospects are limited and what looms ahead is the elimination of this ethnic group. In Afghanistan’s chaotic state not much can be done, but in Pakistan, some analysts believe, that if the government even while beset with problems of separatist movements in Balochistan decides to take action it can clear out the madressahs and sanctuaries of these organisations that dot the countryside from Lasbela to Quetta and beyond. Will it happen?

In the meanwhile, Pakistan is making every effort as evidenced by the army chief’s visit to Kabul accompanied by the British army chief of staff to promote reconciliation. It must, however, now give added urgency to completing the fencing of its border which said to be 85 per cent complete and to try and if protect its Hazaras from the horrors that will be visited upon them in Afghanistan.

Najmuddin A. Shaikh is an accomplished diplomat of Pakistan. Shaikh among his several prestigious postings also served as the Foreign Secretary of his country.

Courtesy: Dawn