BY Shiv Sunny

A withering money plant in an empty pint bottle of beer is the only new addition to 65-year-old Rambai’s tiny two-room set in Ravidas Camp ever since her husband died early this year. She has placed the plant near the entrance, the only source of light in her dingy house.

“I bought the plant for Rs 10 after a neighbour told me it would bring back my son, Mukesh,” Rambai told HT in a feeble voice.

The frail woman continues to live in hope even five years after her two sons, Mukesh and Ram, were held and convicted with four others for gang-raping and killing a physiotherapist in a bus in south Delhi on December 16, 2012 – incident that shook Delhi, sparked outrage across India and triggered a slew of changes in rape laws.

But the money plant has brought little change in terms of luck or money for Rambai. Mukesh, the occasional driver and cleaner of the bus on which the gang rape happened, is on the death row. Rambai barely has any money even to visit him in Tihar Jail. Her older son, Ram – the driver of that bus – had earlier committed ‘suicide’ in Tihar Jail in 2013, forcing her to believe he was guilty.

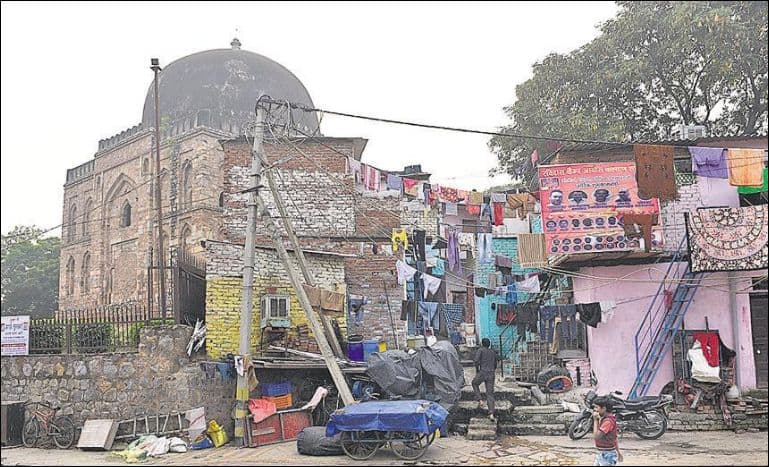

Rambai, who was initially boycotted by the locals, continues to live in Ravidas Camp, a slum in south Delhi’s RK Puram Sector 3.

Apart from her two sons, the slum was home to two other of the four rapists – gym instructor Vinay Sharma and fruit seller Pawan Gupta. The four men’s families continue to live in hope; some of them also in denial.

“Once in two months, I manage to arrange Rs 250-300 for auto fare to visit Mukesh. But when we meet, we barely speak. We both are living in pain. So we just look at each other and cry. Jail people don’t even let me take food for him anymore,” said Rambai.

Still refusing to believe Mukesh’s role in the crime, Rambai spends most of her day and night sleeping in a tiny, dingy room that does not even have a bulb. “Do you bring some news about Mukesh? Has the court said something? Will he be released?” Rambai asked this reporter.

After the Supreme Court upheld the death sentence of the four adult rapists, their fate now hangs with the Indian President. Mukesh’s lawyer recently appealed for a review of the sentence but the Delhi Police sought its rejection even as the Supreme Court reserved its order on the petition. The other two have also filed review petitions. The minor in the case has already released from the juvenile home after serving his sentence and is currently living an anonymous life.

Rambai, meanwhile, has been struggling for money and mostly remains confined to her room ever since her husband died earlier this year, neighbours said. Aware that she is not in the health to work anymore, the slum’s residents have arranged Rs 1,000 as monthly pension for her.

But Rambai wants someone who can be beside her in her loneliness. “If I die, no one will even know for days. I should have given birth to a girl, who would never have got into trouble. The other two families have their daughters looking after them,” said Rambai.

The other two families Rambai was referring to were of Vinay and Pawan, two other convicts, who lived in separate homes, a few metres away, in the same slum.

Unlike Rambai, the families of Vinay and Pawan have been trying to move on in their lives even though they regularly visit their wards in jail and continue to hope for a change. The duo’s sisters have been pillars for their ageing parents.

When Vinay’s younger brother Raj, a class 11 student, and older sister, Manju, found it difficult to move on, they convinced their parents to get their tiny residence coloured. The house was painted in a bright blue colour a year ago, but the family was unable to get going. So Raj decided to cook frequently for his family. “My classmates say cooking helps in keeping life moving,” Raj added.

Unlike his father who found it difficult to retain his housekeeping job at the airport in the initial months of Vinay’s involvement in the crime, Raj had found support in his school friends.

“Raj’s friends knew about Vinay’s character. They knew Raj was different, so they accepted him without getting judgemental. Why should everyone in the family suffer because of one person?” said Manju. The family does not defend Vinay anymore, but they live in hope that he would be “forgiven and released”.

In the same narrow by lane, Pawan’s family drew the curtains on getting to know that a journalist was at their doorstep. “You have done us a lot of good. Now please leave. We have guests at home. We are trying to move on,” a woman sarcastically said from inside.

“The media never quoted us correctly. They would cook up statements after speaking to us. No one cared that our elderly parents were suffering for no fault of theirs. Do grown-up children listen to their parents anymore?” Pawan’s older sister later explained the family’s anger.

“I know how it is going to end up for Pawan and others. But I keep comforting my parents that everything would be fine one day. My mother is disabled in her leg and is hopeful of Pawan’s return. I don’t have the courage to tell them the reality,” said Pawan’s sister who would not reveal her name.

Initially boycotted by other residents of the slum, the three families have now been accepted by the society. “Ideally, we should have barred them from this slum at the very beginning. That would have saved our slum the shame that is part of our history now. But since they have stayed on, we have accepted them. We invite them for every wedding, each function,” said Bihari Lal, the president of the Residents Welfare Association.

Courtesy: Hindustan Times