New York: In a first, US scientists have used stem cells to grow human oesophagus — known as the food pipe — in the laboratory, an advance that will enable personalised disease diagnosis, regenerative therapies.

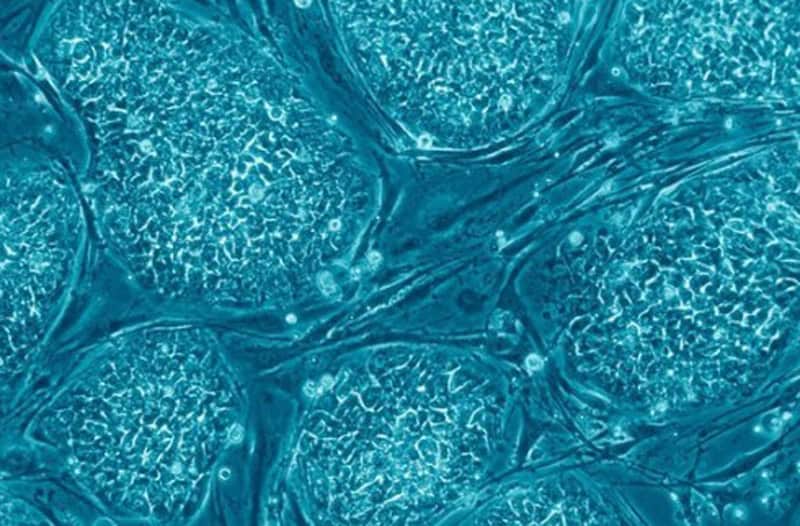

A team from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital in Ohio successfully generated fully formed human oesophageal organoids — tiny version of an organ produced in vitro in three dimensions — using pluripotent stem cells (PSCs).

PSCs are master cells that can potentially produce any cell or tissue the body needs to repair itself.

The oesophageal organoids grew to a length of about 300-800 micrometers in about two months.

“Disorders of the oesophagus and trachea are prevalent enough in people that organoid models of human oesophagus could be greatly beneficial,” said lead investigator Jim Wells, from the hospital.

“In addition to being a new model to study birth defects like oesophageal atresia, the organoids can be used to study diseases like oeosinophilic oesophagitis and Barrett’s metaplasia, or to bioengineer genetically matched oesophageal tissue for individual patients,” he added.

In the study, published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, the team focused on the gene Sox2 and its associated protein — known to trigger oesophageal conditions when their function is disrupted.

The scientists used mice, frogs and human tissue cultures to identify other genes and molecular pathways regulated by Sox2 during oesophagus formation.

During critical stages of embryonic development, the Sox2 gene blocks the programming and action of genetic pathways that direct cells to become respiratory instead of oesophageal.

The Sox2 protein inhibits the signalling of a molecule called Wnt and promotes the formation and survival of oesophageal tissues.

Conversely, the absence of Sox2 during the development process in mice can result in oesophageal agenesis — a condition in which the oesophagus terminates in a pouch and does not connect to the stomach.

Those tests showed the bioengineered and biopsies tissues were strikingly similar in composition, the team said.

Cincinnati Children’s scientists have previously used PSCs to bioengineer human intestine, stomach, colon and liver.

[source_without_link]IANS[/source_without_link]