One evening in the late 1990s, as a cub reporter working for The Asian Age, founded and then edited by eminent journalist M J Akbar, I landed at the iconic Nehru Centre in Mumbai. It was a lecture by Samuel Huntington, the famous American scholar who had stirred a huge controversy with his Clash of Civilizations hypothesis. After Huntington’s speech, Dr Zakaria spoke and, while acknowledging the renowned scholar’s debt in mentoring the Zakarias’ son the famous author and journalist Fareed Zakaria, Dr Zakaria disagreed with Huntington’s hypothesis and attacked him for spreading fear among the peace-loving section of the world community.

That was the first time I saw Dr Zakaria. Subsequently, I attended a screening of a documentary made by a British channel on the eve of 50 years of India’s Independence in 1997. The documentary complained Zakaria, had truncated version of his interview and post-screening Dr Zakaria was understandably disturbed and livid. In my excitement to have got a “hot” story about a leading Islamic scholar like Dr Zakaria trashing a documentary by a British channel I reported it in the paper but wrongly said that it was produced by the BBC. Next day the BBC sent a letter to my editor denying its ownership. It was a huge embarrassment for me, the editor and the paper and, the then resident editor, rapped me for such a lapse and carelessness while reporting. To my pleasant surprise, Dr Zakaria didn’t pull me up, forgetting and forgiving with a remark that it was a misreporting.

Dr Zakaria and his wife Madam Fatma Zakaria were very close to M J Akbar and Dr Zakaria could have got me fired for the blunder that I had committed. But Dr Zakaria saw it as a minor mistake on the part of a young, fledgeling reporter and didn’t make it into a big issue. I fell in love with the scholar-politician for his magnanimity and sense of justice.

For the next decade or so I remained immensely close to the Zakarias. Hardly a week passed when I didn’t call doctor sahib or he didn’t inquire about my progress as a journalist. I can’t remember the number of times I quoted him for stories or interviewed him for The Asian Age or The India Express, the paper I left in 2005 to join The Times of India. He was happy that I joined TOI, the newspaper he had contributed to for decades. Sadly, he didn’t live long to see my works in TOI, except the first story which announced my arrival to the Times. It was about Sare Jahan Se Accha completing a century and doctor sahib, as always, was effusive in his praise for me for this front-page story which in a way also announced my arrival to the Times of India.

I cannot forget a note that he wrote on one of his books he gifted me. Seated at his spacious study at the Cuffe Parade House in South Mumbai, in longhand, doctor sahib wrote: “To Mohammed Wajihuddin for whose bright future I am genuinely concerned.” It was a big compliment for me. I felt adopted by the Zakarias who showered unreserved love and affection on me. There was no artificiality in doctor sahib’s expression of concern and love for a boy who had arrived in the city from the backwaters of Bihar without a godfather. After his passing away, I missed him a lot and miss him every day, every moment.

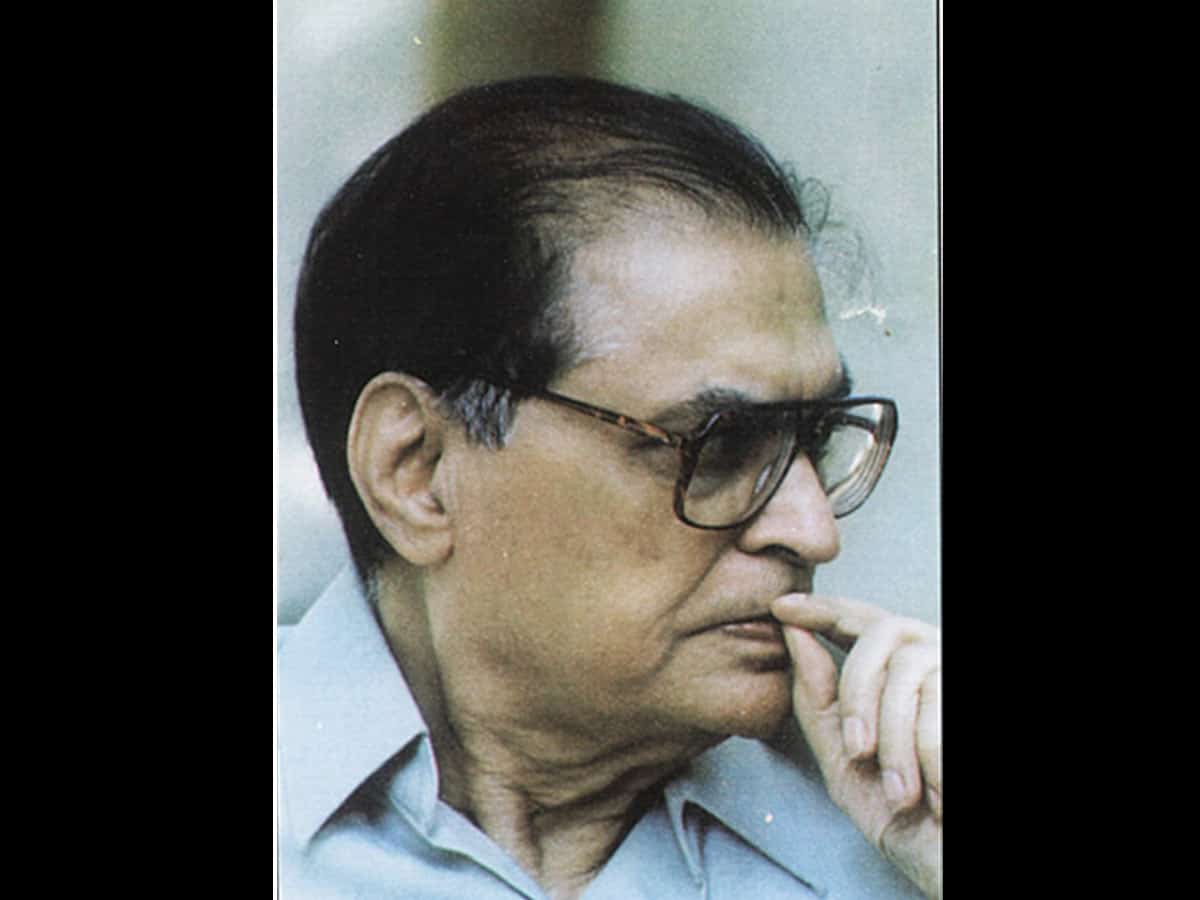

Dr Zakaria belonged to a generation which had not only witnessed the horrors of partition but had deeply felt pained at the vivisection of India into Islamic Pakisan and Secular India. Son of a maulvi in Nala Sopara, Zakaria scaled the height of scholarship and politics mainly because of his love for reading and a drive to excel.

A brilliant student, he devoured books on history, fiction, law, religion and everything between them. He had befriended Bernard Shaw, heard Harold Laski and met Bapu the Mahtma who always remained a paragon of truth and non-violence to Zakaria. Even as a student, both in Bombay and in London, he wrote for some leading newspapers of the day. An argumentative mind, he would not take things on their face value. He would question the status quo and side with the victims.

A patriot to the core, Zakaria never lost hope in the Hindu-Muslim unity and never forgave Mohammed Ali Jinnah for formulating the Two-Nation Theory which caused immeasurable damage to the sub-continent’s Muslims. In his autobiographical book The Price of Partitionwhich release function I had the fortune to attend he has detailed the circumstances leading to the partition of India. He would often quote the famous Urdu couplet about the disaster that partition brought: Lamhon ne khata ki thi/sadiyon ne saza payee.

In his lucid prose which, as Zakaria confesses in almost all his books that he authored, was fine-tuned by the veteran editor and his better half Madam Fatma, Zakaria has quoted several interesting anecdotes about Jinnah whom his supporters called Quaid-e-Azam (the leader) but who actually misled the sub-continent’s Muslims. The pork-eating Jinnah who loved his whisky had nothing to do with the genuine concerns of the Muslims. He was authoritarian, egotist and desperate to see his dream of carving out Pakistan, the so-called Pure land for Muslims. One of the anecdotes in Zakaria’s immensely readable book goes like this: “Jinnah had started reorganizing the League after the assembly elections in 1937; he was on an enticing spree. Hasrat Mohani, who was a firebrand, went to see Jinnah on some urgent work at his bungalow. He had not taken an appointment. It was after dusk; Jinnah was enjoying his peg of whisky. He called Mohani to his room and thinking then that he was more a revolutionary than an orthodox Muslim, offered him a drink. Mohani, somewhat baffled, said that he wished he had as little fear of God as Jinnah had. Jinnah retorted: “No, Maulana! You are wrong. I have more faith in His mercy than you have.”

He was a successful politician who even represented India at the United States to counter the arguments of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, then Pakistan’s foreign minister and later the Prime Minister, on the dispute over Kashmir. Besides, Zakaria was a passionate scholar of Islam. His seminal work Muhammad and the Quran, written in response to Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, is a labour of love for which Muslims will be eternally indebted to him. About the huge positive response this book received from noted scholars from across the world, Dr Zakaria once told me: “After reading this book, a big Pakistani Maulana said, “Mujhe nahim maloom Dr Zakaria ne kitni neki or aur kitne gunah kiye hain lekin main gawahi deta hoon key eh kitab unki bakhshayesh ka zariya banegi.” Truly, if nothing else, at least this book will inshallah help our late doctor sahib find a place in jannah.

His love for the poet-philosopher Allama Iqbal was immense. He defended Iqbal like few in India did. His book on Allama Iqbal, penned to prove that Iqbal was wrongly credited with fathering the idea of Pakistan, is testimony to Zakaria’s love and respect for Iqabl who was undoubtedly a great poet but a failed politician. Dr Zakaria never failed to quote the famous line from Iqbal’s Naya Shivala –Pather ki moorton mein samjha hai tu khuda hai/khake watan ka mujhko har zarra devta hai–whenever he needed to show Iqbal or other Indian Muslims as nationalists.

One thing that is of great relevance to us today is Dr Zakaria’s unshakeable faith in Kashmir’s accession to India. He had even penned a poem on Kashmir, expressing his love for the valley and why it needed to be with India. He justifiably believed that, if Kashmir secedes from India, it will not only be ruinous for the Kashmiris, but Muslims in the rest of India will have to pay heavily for this crime. As anti-Muslim hysteria grips parts of India in the aftermath of the recent terror attack on the Amarnath Yatri, Dr Zakaria’s fears only seem true. It is in the interest of Indian Muslims that Kashmir remains an integral part of India.

Sadly today there is no one of Dr Zakaria’s caliber, scholarship and forceful articulation to bat for Indian Muslims either in the media or in the corridors of power, the two arenas that are increasingly getting poisoned. As majotarianism marches ahead, threatening to turn the secular India into a Hindu rashtra, the absence of a patriot, politician and scholar like Zakaria is greatly felt.

(The author, a journalist with The Times of India, presented this paper at the one-day seminar on Dr Rafiq Zakaria on July 15, 2017 at Aurangabad)

Mohammed Wajihuddin, a senior journalist, is associated with The Times of India, Mumbai. This piece has been picked up from his blog.