A recent tweet from the Congress leader and former chief minister of Madhya Pradesh, Kamal Nath, runs thus: “It is really praiseworthy that Muslim community persons along with the old woman’s two sons carried the body on their shoulders for her last rites. This has set an example in society.” Nath was referring to an incident in Indore, in which the death of a woman had left her sons helpless. Their relatives could not come because of the lockdown. The cremation ground, too, was about 2.5 kilometres away, but there was no van to take the body there. So their Muslim neighbours organized everything, from carrying the body on foot to arranging for the last rites. They also recalled the affection the woman had showered on them when they were young.

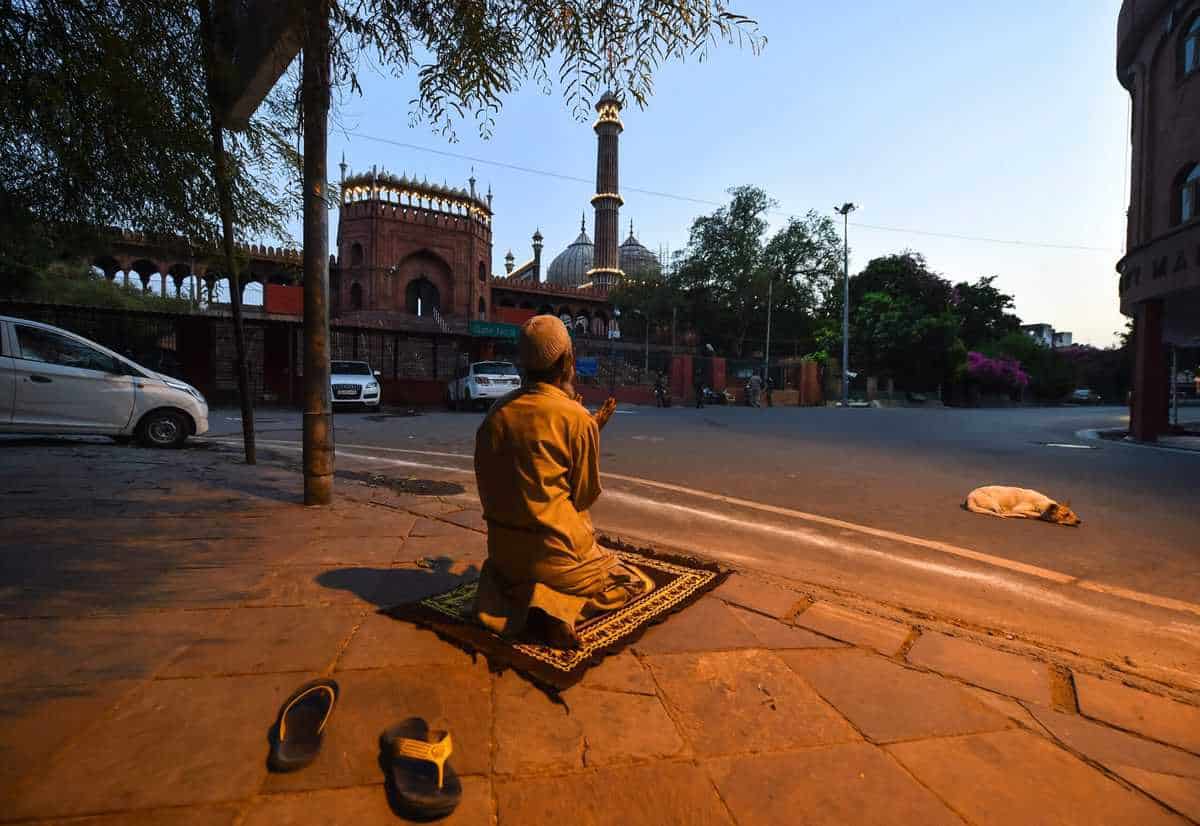

In an atmosphere that has been increasingly poisoned with hostility — to put it mildly — against India’s largest minority community,

Nath’s effusions are understandable. Even if memories of the violence, bloodshed and deaths in northeastern Delhi in February have been obliterated in the public mind by the obsessive fear of Covid-19, and their facts no longer left open to unbiased examination, the earlier period of the lockdown itself rang with accusations against the minority community for spreading the virus, because of the Tablighi Jamaat held in Delhi. There is no doubt that the meet was ill-advised at the time, and the organizers should have been wiser. But it must not be forgotten too that permission for the meeting was granted by the government. In the discourse of blame that followed the discovery of infections of a large number of people who had attended the meeting, the government’s role somehow vanished. This divisive context cannot be ignored in Nath’s tweet in response to the Indore episode, to which he had added: “It reflects our Ganga-Jamuni culture and such scenes enhance mutual love and brotherhood.”

It is not Nath’s response that is in question here — it is irreproachable and welcome — but the need for it should disconcert us. Why should a perfectly humane and neighbourly act, which also has a history of warmth and affection behind it, be selected for special mention, even display? The recent exacerbation of politically encouraged hatred has transformed normal human actions into “scenes” that are “example[s] in society”. In the most positive comments and responses, there is an involuntary surrender to the strident and enveloping rhetoric of difference propagated by the sangh parivar. A neighbourly deed can be seen as praiseworthy only because the identity of one particular community has to be foregrounded.

News reports indicate other incidents too, whether near Lucknow or in Hyderabad, where either the lockdown or an unreasoning fear of infection by Covid-19 — even if the person who died did not have it — prompted Muslim neighbours to help in the funeral of Hindu men and women. As a Kashmiri man who stays with his brother in rented rooms in Burdwan during the season for shawl trading put it, religion is a personal belief but humanity is universal. Their part-year landlady, with whose family they have a long and warm relationship, has ensured that the brothers can have their sehri and iftar just as they would at home during Ramadan. The practice of their faith should not be affected because they could not return when the lockdown descended. The situation enacts a beautiful human relationship. Yet a civilized society of a still secular country might have the grace to feel ashamed that these events should be considered news because of their rarity. The reports, again irreproachable, welcome and deeply heartening in the present — deplorable — circumstances (and I am not referring to Covid-19), indicate the depths of routine incivility, insensitiveness and even crudeness to which we as a society have sunk.

This is not to suggest for a moment that hatred between communities is a new phenomenon, brought about by any particular political regime. Mutual distrust, hostility, violence are all part of India’s tragic history. But beyond all this, there was till the recent past an aspiration towards equality in policy, an effort to give substance to the idea of secularism in spite of prejudice and wounded memory, a hesitation in so-called polite society to give voice to baseless assumptions and allegations, even an awareness in many regions and segments of society of bonds that persist in spite of expressed differences and distances in daily living. But political legitimacy given to the outpouring of hatred that has grown in power and gradually taken over everyday discourse since the Babri Masjid demolition has ripped the delicate wrappings off the pretence of reason and civilized hesitation. In this environment, any ‘natural’, human exchange between communities seems extraordinary.

Accusations against the minority community of spreading the virus, however, did not go down well in global media. In an attempt at damage control, the prime minister said in a LinkedIn post that Covid-19 does not see race, religion, colour, caste, language or borders before striking. Perhaps this banal comment is more important for what it does not say. The virus does not discriminate, the government does. Hence the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, promulgated to extend citizenship on comfortable terms to people of all faiths except Islam who wish to escape religious oppression in selected neighbouring countries. Protests against the new law were swelling throughout the country when the virus struck. The unceasing fear of infection and the growing difficulties of carrying on life under lockdown day after day, together with economic insecurity — terrifying for a huge number of citizens — may have made people forget about police and right-wing terror unleashed on protesting students inside campuses, in Jamia Millia Islamia and Jawaharlal Nehru University, for example. The government, however, has neither forgotten nor stopped in its tracks. Arrests of students and former students, usually from the minority community, of the two universities for alleged conspiracy and incitement of the violence in northeast Delhi in February — not just for participating in anti-CAA protests — by the special cell of the Delhi police continue apace.

Most of the arrests have been made under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, the stringency of which derives from the fact that it is meant to be applied against those who target the integrity and sovereignty of India. Anand Teltumbde and Gautam Navlakha, writers and activists, have also been arrested under the same law. They go to join in prison the other nine activists including journalists, teachers and lawyers associated with upholding the rights of the poor and of Dalits, all of them jailed in the Bhima-Koregaon violence case of 2018, either for incitement, or conspiracy, or a plan to assassinate the prime minister. Dissenters, protesters, rationalists campaigning for a scientific approach cannot be allowed to run loose. The lockdown ensures lower visibility, and protesters can be picked up much faster than the murderers of Gauri Lankesh, Narendra Dabholkar, M.M. Kalburgi and Govind Pansare. Just as, on a different plane, changes in Kashmir’s laws regarding domicile and reservations in local government jobs that had become possible after the scrapping of the Valley’s special status in August, 2019 are being made. More smoothly accomplished during a national lockdown, obviously. Fear keeps everyone home.

The virus does not see before it strikes. The government does.

By Bhaswati Chakravorty