Anyone who makes New Year’s resolutions and believes that such promises will be kept is halfway to becoming a politician. Resolutions (like the second marriages of Winston Churchill’s definition) are the triumph of hope over experience.

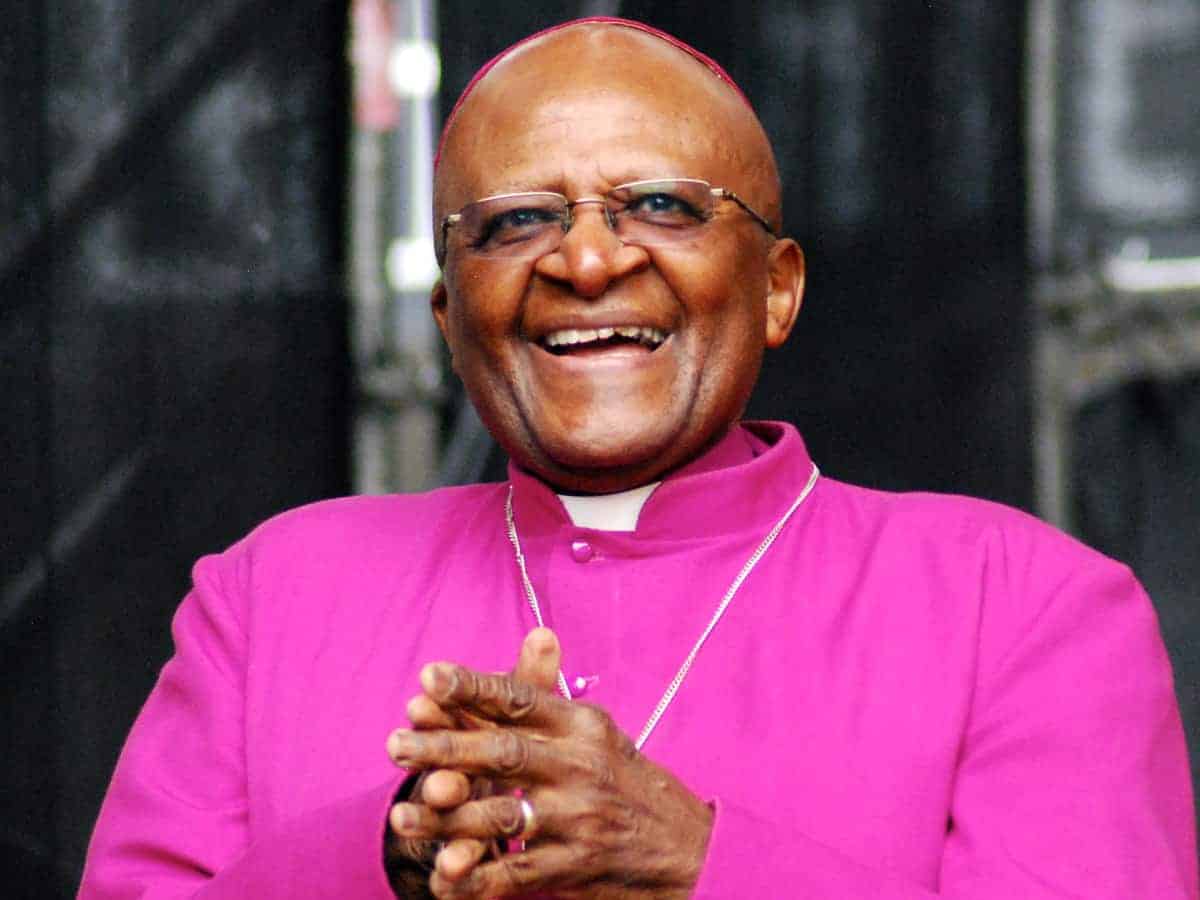

Only the brave will recall the outgoing year, dying, un-mourned under a pall cast by Covid. One death, though not Covid-related, has left humanity diminished. The South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu passed away on 26 December, the day after the anniversary of the birth of Jesus Christ.

Archbishop Tutu’s memory is laden with honours, amongst them the Nobel Peace Prize which he won in 1984. He had been nominated thrice before. To its discredit, the Nobel Prize Selection Committee settled on Tutu not as its first choice but as a safe second bet. It felt Nelson Mandela (then in jail on Robben Island) would have been too controversial. Mandela would be awarded the same prize, nine years later, in 1993.

Destiny linked their names to a common cause. Desmond Tutu used every platform to rail against the repressive apartheid regime; Nelson Mandela endured incarceration for 27 years as its most prominent black victim. They met after thirty-five years in February 1990, when the white PM de Klerk released Mandela from captivity. Mandela became South Africa’s first black president, Tutu the ‘people’s archbishop.’

Mandela recognised Tutu’s powers of conciliation when in 1994, as president, he nominated Desmond Tutu on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). ‘The TRC adopted a threefold approach: the first being confession, with those responsible for human rights abuses fully disclosing their activities, the second being forgiveness in the form of a legal amnesty from prosecution, and the third being restitution, with the perpetrators making amends to their victims.’

The TRC heard confessionals from a gamut of victims and perpetrators for over two years, between 1996 and 1998. On many occasions, Tutu broke down, moved by the accounts of brutality – by white against black, even black against black.

I was privileged to meet Archbishop Tutu in his Cape Town office in June 2008. He had retired by then, becoming a roving voice against injustice, speaking fearlessly on diverse issues such as the environment, Tibetan atrocities, Guantanamo Bay internees, the Arab-Israeli conflict, and LGBT rights. He condemned the Iraq war for which he held president George W. Bush and PM Tony Blair criminally culpable.

I had called on the archbishop with a team of bureaucrats. We were on a study tour. They of course wanted an audience with Nelson Mandela but had to settle, like the Nobel Committee, on Desmond Tutu as a consolation prize.

Tutu worked from a nondescript flat in suburbia – modest, functional. He entered the room wearing casual clothes. The expansive smile that disarmed his audiences world-wide illuminated the room. We sat on chairs beneath a large appliqué quilt showing numerous hands linked in comradeship.

What does one say to an Archbishop, a Nobel Prize winner and such a model humanist?

I began by complimenting the TRC and his stewardship of it. I mentioned its emphasis on forgiveness rather than punishment, something that distinguished it from the vengeful Nuremberg trials of 1945-46 after the Second World War.

It seemed appropriate to talk about his innate Christianity, the moral strength that allowed him to forgive his enemies as he strove to do from within the TRC. I startled him by saying that the TRC had shown ultra-Christian charity, for even the founder of their faith had forgiven his oppressors only once, while on the cross.

Desmond Tutu died the day after the anniversary of his Lord’s nativity. Can we glean any messages from their lives? I believe we can. That spirit of forgiveness, like some benign form of Covid variant, can be transmitted from South Africa to Pakistan.

For 2022, let politicians resolve to replace hatred of each other with the kinship of brotherhood, since they all stand this side of the grave.

Let public representatives resolve not to posture but to take a stand on social issues – health, education, urbanisation, human rights – everything that will affect their unborn descendants.

Let the judiciary resolve to dispense justice not as a patrician favour, but as a plebeian right.

Let every militant group resolve to lay down its weapons of individual destruction.

Let the military establishment come out from behind its pips into the glare of accountability.

Let 2022 – the 75th anniversary of our independence – be the year in which 220 million of us acknowledge our dependence on each other. Hate has rusted our hearts; only forgiveness can restore their sheen.

I will repeat these resolutions for 2023. Desmond Tutu had warned me: ‘There is nothing more difficult than waking someone who is only pretending to be asleep.’

Fakir S Aijazuddin is a noted thinker and columnist of Pakistan