Lucknow: In Greek drama, it was normal to spring a god on a cluster of befuddled mortals to deliver the solution that had been eluding them, and the god was introduced on stage using a machine. This gave rise to the term Deus ex Machina or god out of a machine. In India, politicians love to cast the Supreme Court in the role of the mechanism that delivers the problem-solving divine revelation. But there are good reasons why the Court should refuse to play Deus ex Machina in the Ayodhya dispute.

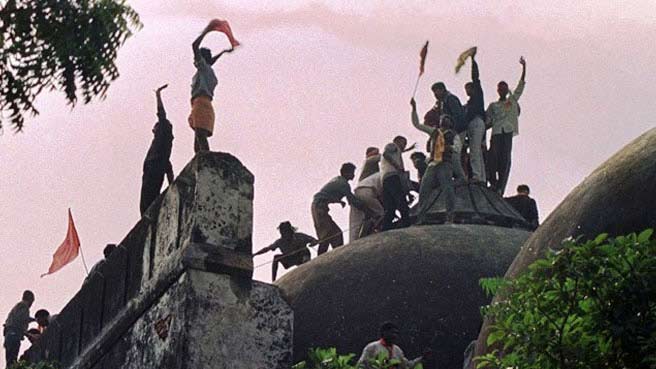

The question before the Court is not whether a temple should be built at the site of the Babri mosque that was demolished on December 6, 1992. The Court’s job is to determine ownership of the land on which the mosque once stood and on which a makeshift temple has been built, housing an idol of Ram Lalla. There are several claimants: the Sunni Central Wakf Board and the Nirmohi Akhada, apart from Ram Lalla (a colonial device allows Hindu deities to take part in legal disputes as juridical persons). Suppose the legal documents uphold the claim of the Sunni Wakf Board; will the problem be settled, and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, Subramanian Swamy, BJP and all those who have been campaigning for a Ram temple at site of the Babri mosque suddenly let the law supercede faith and abandon their quest?

The Ram Janmabhoomi campaign must be understood as a political project at its core. The building of a Ram temple was incidental to the primary aim of demolishing the mosque built by Babar, seen as a symbol of Muslim suzerainty over Hindus, albeit in the medieval past. In the slogan, ‘Mandir wahin banayenge’, the stress was on ‘wahin’, meaning here the mosque stood. The only way to build a temple where the mosque stood was to demolish the mosque first, to make way for the temple. Building a temple is a cleanup job, to validate the claim that the goal was not really to demolish the mosque, but to build a temple to Lord Ram at the site of his birth. The fact, however, is that there are multiple places in Ayodhya that lay claim to being the birthplace of Ram. Once the mosque was demolished, the act proved that secular India cannot prevent majoritarian mobilisation from pursuing goals that might be illegal but are matters of faith. This was the objective of the Sangh Parivar, which holds the democratic Constitution that promises equality to all citizens to be a fraud and seeks to redefine Indian nationhood as Hindutva. Proving that point helped them emerge a political force that has grown over the two and a half decades since the demolition.

It mattered to democracy, respect for history and the rule of law that the mosque should not forcibly be demolished. When it was brought down, the damage was done, which all the cries of protest, condemnation and regret that followed could not undo. After the physical structure of the mosque has been demolished, it matters little if a temple is built there or a memorial, or a walled enclosure of barren land, bereft of flowers, bees, birds and song. It is of little political consequence. What matters politically is the metaphorical significance of the mosque: acceptance of history as it transpired, democratic commitment to minority rights and the rule of law and carrying forward a tradition of this land that llowed multiple cultures to flourish and co-exist in mutual acceptance, rather than mere tolerance. Pursuing the truth of the metaphor is different from scrambling for the physical debris of the demolished mosque.

The Kerala HC once told two warring factions of a Christian denomination that had taken their dispute to it to sort the problem out among themselves, the dispute falling outside the realm of temporal law. The Supreme Court would do well to similarly tell politicians to sort out their political problem outside the Court, without getting drawn into a uicksand of partisan accusations that would erode the authority of the court and damage the nation further.

(The article was first published on Economic Times written by T K Arun)