This open space in your newspaper should not become a cemetery. Yet, persons whose lives deserve celebration are passing on with such frequency nowadays that a tribute to them here is unavoidable. Hence, another piece, in memoriam.

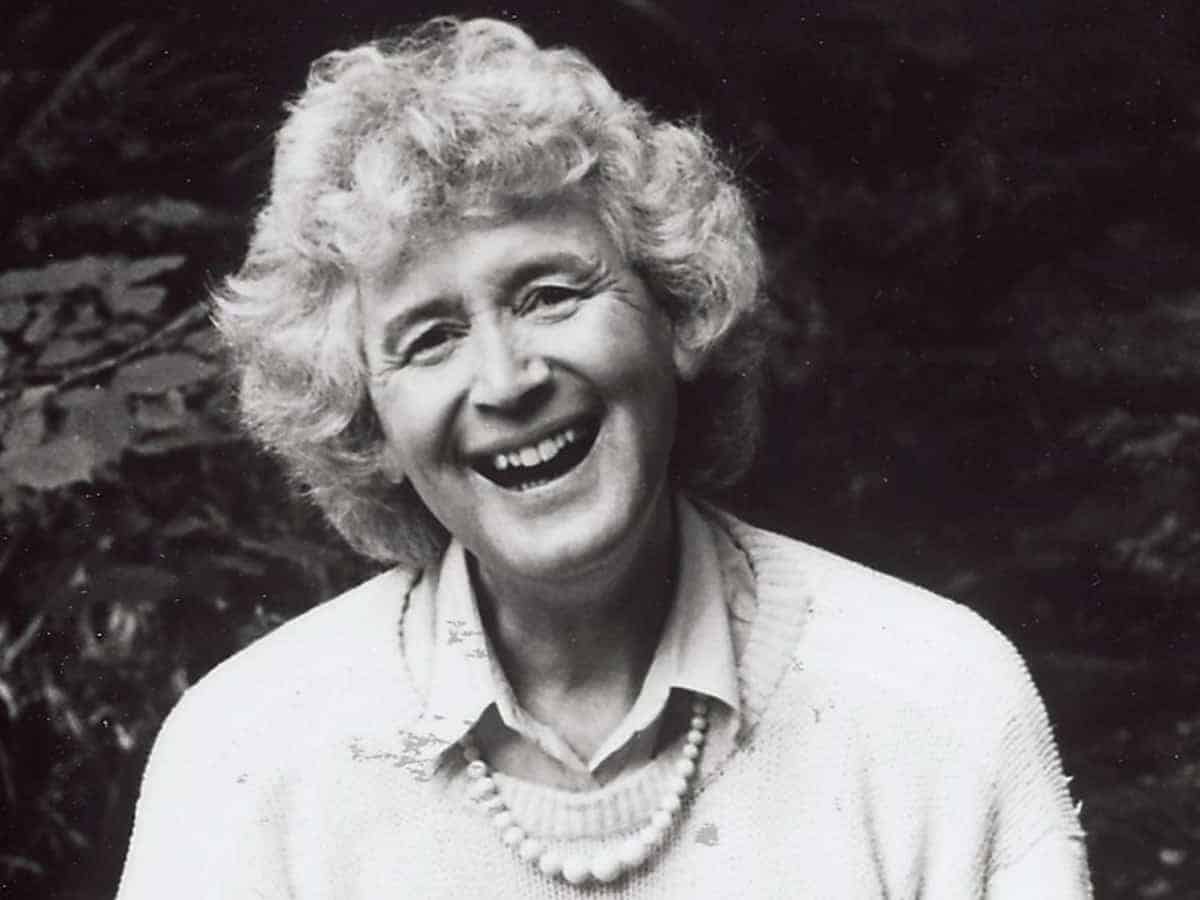

This is for the Raj historian Jan Morris, who died on 20 November 2020. Jan Morris led a full life, in fact two lives, for midway, at the age of forty-six, in 1972, James Morris changed gender. He recounted the experience of that improbable transformation in a searingly frank book Conundrum (1974). He was put to sleep as a man in a hospital room in Casablanca, and woke up as a woman. The next forty-eight years were spent as Jan Morris.

Initially, James Morris was married to Elizabeth. They shared five children. He served in the British army, studied at Oxford and then achieved distinction as a journalist. In 1953, he pre-empted his colleagues by breaking the news of the ascent of Mount Everest. That luck continued. During the Suez crisis of 1956, he exposed the secret collusion between the British, the French and the Israeli governments to invade Egypt. In 1982, Morris saw more clearly than Mrs Margaret Thatcher the sterility of the Falklands War, her imperial claim to islands 8,000 miles away from mainland Britain. It was the jingoistic opposite, the very antithesis of Pax Britannica, Jan Morris’s expansive trilogy on the British raj.

Morris authored over forty books, from Coast to Coast (1956) to Thinking Again (2020). One manuscript – Allegorizings – lies with Morris’ publisher, to be printed now that she is dead. Morris, although labelled as a ‘travel writer’, preferred to be remembered as a chronicler of ‘people and places’. She loved cities with an almost physical passion. Her book on her alma mater Oxford – the city of dreaming spires – is at par with Evelyn Waugh’s evocation of that stone crucible of learning in his novel Brideshead Revisited. Her tribute to Venice – that city awash with canals – is a modern rival to John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice, published a century earlier.

Morris as James in his Venice (1960) admitted a young man’s infatuation with Venice – ‘the loveliest city in the world, only asking to be admired’ by him, ‘a writer in the full powers of young maturity, strong in physique, eager in passion.’ Twenty years later, Morris, this time as Jan, returned to Venice to write The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage (1980). She draped it with an imperial mantle: ‘Rome apart, theirs was the first and the longest-lived of the European overseas empires.’

Morris visited almost every major city in the world; her inimitable essays on each became her Journeys (1984). She visited Pakistan, certainly once. She refers to the ‘mammoth hangar built at Karachi in 1930 to house the doomed airship R101’; the Holy Trinity church (now the Anglican cathedral), built in 1855 to replace the temporary ‘Divine Shed’; and ‘the delightful Frere Hall, a display of Gothic pinnacles, buttresses and stained glass…a Victorian monstrosity.’

But it is Lahore that becomes her land-locked Venice: ‘It is a fine city, no doubt about it [.] Many Anglo-Indians thought it the finest in India, but then the British, on the whole, preferred the Muslim ambiance to the Hindu, and the presence of the great Moguls even in memory tempered their insularity rather, and brought out the best in them.’ She notices the ‘twin-domed towers, windows in the Moorish shape’ of the Town Hall, opened by Queen Victoria’s grandson Prince Albert Victor in 1890. And she succumbs to the charm of the Lahore Museum – ‘where the moment you set your foot inside it, its magic is all around you […] the whole building is rather dim-lit, almost opaque in fact, as though wood-smoke is perpetually drifting through it.’

Many social historians have written about the traumas of August 1947. Few have done so with the searing simplicity Jan Morris did. She describes the fortified Lahore railway station (built in 1864, after the 1857 insurrection), convertible instantly into a ‘huge bunker’. Morris concludes: ‘Lahore railway station never went into action, but from then until the end of the Raj, in times of trouble British soldiers manned its beguiling ramparts; and when they prepared to leave in 1947, and the Muslims and the Hindus of the Punjab leapt at each other’s throats, ironically upon its platforms the dead were laid out.’

Jan Morris often derided the British institutions she described with such finesse. She accepted a CBE, with reluctance, because her heart belonged to that western rump of the British Isles – Wales. Who but a fervent Welsh separatist would have devoted a whole volume to it, titled Wales: Epic Views Of A Small Country?