London: One of the skin’s defences against environmental assault can help tumours to grow when skin is exposed to chronic inflammation, researchers have found.

The IgE antibody is most commonly known for its inadvertent involvement in allergic reactions, but it is commonly found in healthy skin and believed to protect against harmful substances or parasitic infections.

However, the study, published in the journal eLife, shows that chronic inflammation caused by repeated exposure to skin-irritating chemicals may turn this helpful defence into a harmful one.

Learning more about this process may help scientists develop ways to prevent or treat skin cancer.

“Chronic inflammation has been linked to many types of cancers, and may cause these by enabling the growth and survival of cells with cancer-causing mutations, but the exact steps in this process and the role of IgE were not previously clear,” said study lead author Mark Hayes from Imperial College London in UK.

To learn more, the research team looked at what happened after inflammation-causing substances were applied to the skin.

They saw an increase in the amount of IgE produced and that immune cells called basophils were attracted to the skin.

When the basophils were activated by IgE, they stimulated skin cells to divide and grow.

“IgE fortifies the skin barrier defences by promoting cell growth to thicken the surface of the skin in response to noxious stimuli,” Hayes noted.

However, this response should be temporary. If it persists in the long term, it may lead to tumour growth, the researcher said.

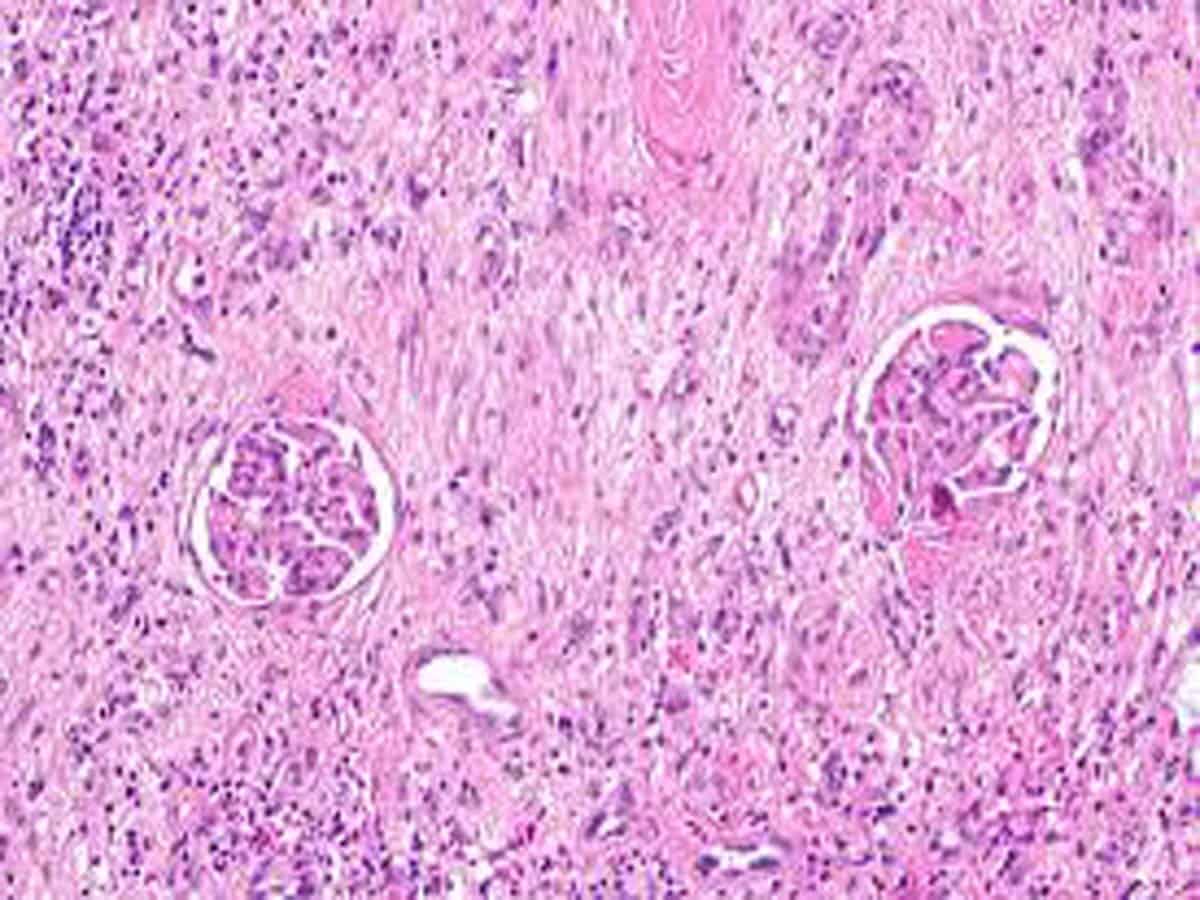

The team found that in mice with cancer-causing mutations, chronic activation of IgE caused by inflammation subverts its protective effects and supports the growth of precancerous skin cells into tumours.

On the other hand, mice lacking IgE were protected from developing these tumours in response to inflammation.

Surprisingly, the results of a previous study by the team showed that IgE protects mice against cancer-causing substances that damage DNA.

This suggests that the mechanism of tumour growth, and the role of IgE in this process, may depend on different kinds of environmental exposure.

“Our previous and current findings reveal a strong link between IgE and cancer,” said senior author Jessica Strid.

“But the biological consequences of IgE engagement in the skin clearly depends on the nature of the antibodies and the microenvironment in which the tumour grows,” Strid added.