By Ramachandra Guha

New Delhi: The recent clashes in Ladakh, leading to the tragic deaths of 20 Indian soldiers, prompt a fresh look at our government’s policy towards China. The military, strategic and economic aspects of that relationship I leave to others more qualified in those fields. Writing here as a historian, I wish to draw attention to the curious parallels between the policy towards China of our first Prime Minister and our current Prime Minister.

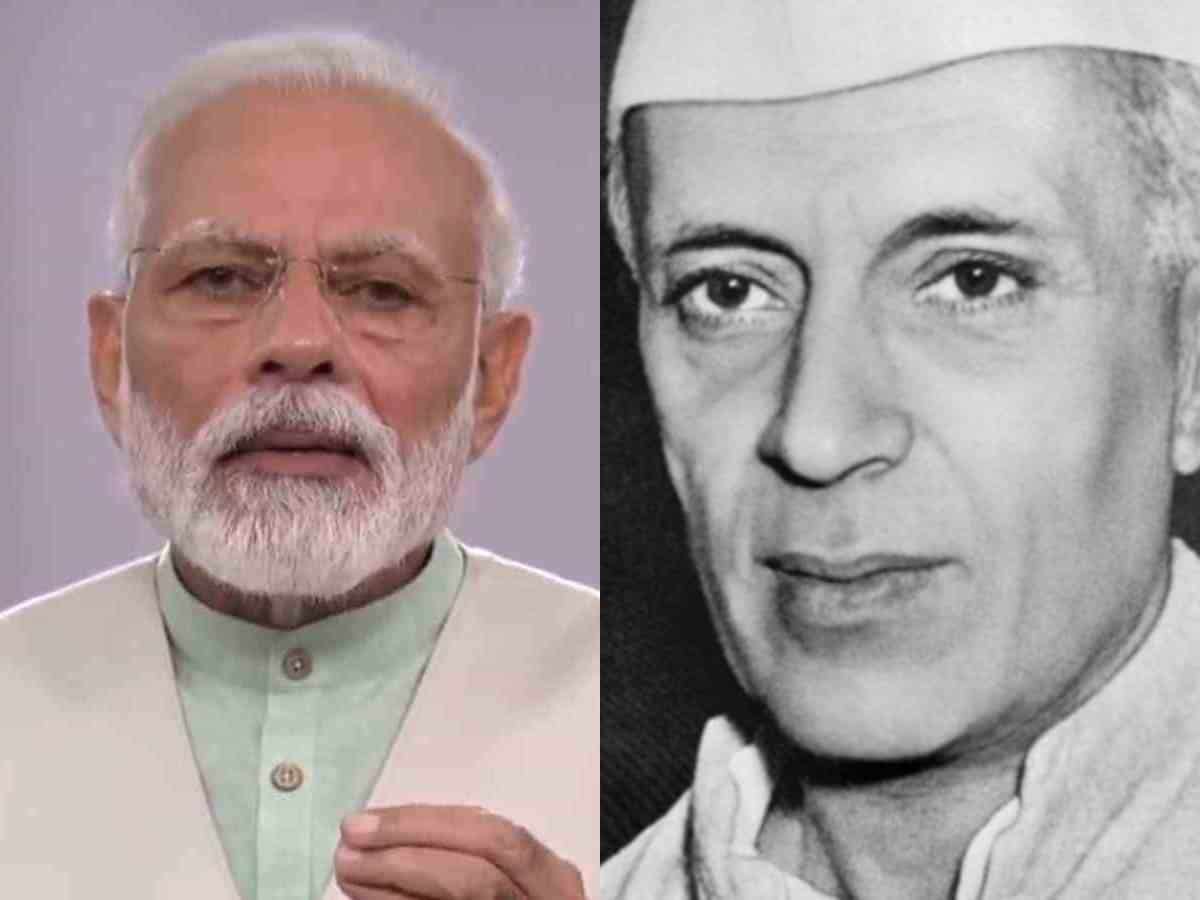

That in terms of political ideology Jawaharlal Nehru and Narendra Modi are poles apart is well known. Modi does not share Nehru’s commitment to Hindu-Muslim harmony or his interest in scientific research and technological education. Modi’s attitude towards his critics is far more abrasive than Nehru’s ever was.

And yet, for all that separates them, Nehru and Modi exhibit noticeable similarities in how they have dealt with our largest and most powerful neighbour. Like our first Prime Minister, our current Prime Minister has also acted in the belief that by cultivating personal friendships with the top leaders of communist China, a deeper bond of solidarity would be created between the people of the two countries.

Jawaharlal Nehru’s response

Back in 1954, Jawaharlal Nehru visited China to have discussions with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. His hosts, seeking to flatter him, brought a million people out to the streets of Beijing, prompting Nehru to write to a friend: “I sensed such a tremendous emotional response from the Chinese that I was amazed.”

On his return to India, Nehru addressed a large public meeting at the Calcutta Maidan. Here, he told the audience that “the people of China do not want war”; they were apparently too busy uniting their country and ridding it of poverty. Speaking about the “mighty welcome” he had received in China, he remarked that this was “not because I am Jawaharlal with any special ability, but because I am the Prime Minister of India for which the Chinese people cherish in their hearts the greatest of love and with which they want to maintain the friendliest of relations”.

It is unlikely that our current Prime Minister has read or heard of this speech. Yet its sentiments were strikingly echoed in a speech that Narendra Modi made in Wuhan in April 2018, after meetings with Xi Jinping. Here, Modi effusively told his Chinese counterpart: “Very positive environment [has been] created through the informal summit and you have personally contributed to [it] in a big way. It’s a sign of your affection for India that you have hosted me twice in China outside Beijing. The people of India feel really proud that I’m the first Prime Minister of India for whom you have come out of the capital twice to receive me.” A lyrical ode to the unbreakable bond between the two countries followed, with Modi speaking of how “the culture of both India and China is based along the river banks”, of how “India and China acted as engines for global economic growth for 1600 years out of the 2000 years”.

The meeting at Wuhan had been preceded by a meeting in Ahmedabad in September 2014, where the two leaders chatted on a specially-erected jhula along the Sabarmati River in Ahmedabad. The following May, Modi made his first visit to China as India’s Prime Minister. Here, in a speech in Shanghai, he boasted of his friendship with Xi Jinping that “two heads of states are meeting with such affinity, closeness and companionship, which is ‘plus one’, better than the traditional talks of global relations, and to understand and appreciate this ‘plus one’ friendship will take time for many”.

Recent ‘summit’ meeting with Xi

Modi’s most recent ‘summit’ meeting with Xi was held at Mahabalipuram in October 2019. Afterwards, a government of India website put up a picture gallery of the two leaders, alongside a text that spoke of how “in the backdrop of the 7th century rock-cut monuments and sculptures…the leaders of India and China sipped coconut water and shared their hopes for a new phase in India-China relations, marked by win-win cooperation, greater trust and understanding of each other’s core interests and aspirations. The chemistry between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping shone anew as the former took his honoured guest around the Group of Monuments at the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Mahabalipuram, followed by a sumptuous informal dinner at the scenic Shore Temple”. The Prime Minister’s personal website also had a puff article, which proclaimed that this meeting between the two leaders would “add great momentum to India-China relations. This will benefit the people of our nations and the world”.

In the six years that Narendra Modi has been Prime Minister of India, he and Xi Jinping have met no fewer than 18 times. These manifestations of the “Wuhan Spirit” and “Chennai Connect” constitute, as it were, an updated version of Nehru’s “Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai”. If the Indian Prime Minister and the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party could be friends, so would the people of their two countries. That is how the argument ran. Narendra Modi has now belatedly discovered, as Jawaharlal Nehru did before him, that a naïve trust in the goodness of Chinese intentions is altogether misplaced.

Deen Dayal Upadhyaya

When, in September 1959, clashes broke out between Chinese and Indian troops on the border, prominent RSS ideologue Deen Dayal Upadhyaya wrote a series of articles about Nehru’s failed China policy. “Only he [Nehru] knows when a crisis is not a crisis,” remarked Upadhyaya sarcastically. Only Nehru knew, he sneered, “how to emit smoke without fire and how to arrest a conflagration in a Niagara of verbiage!” In the opinion of the Jana Sangh leader, “the present situation is the result of complacency on the part of the Prime Minister. It seems that he was reluctant to take any action till the situation became really grave”. Why were Nehru’s China policies a failure, asked Upadhyaya – “Is it plain ignorance? Is it simple cowardice? Or it is a simple national policy induced by military weakness, ideological ambiguities and weakening of nationalism?” (These quotes are taken from articles by Upadhyaya in the Organiser, dated 7, 14, and 21 September 1959).

Narendra Modi’s admiration for Deen Dayal Upadhyaya is a matter of record. One wonders what, if Upadhyaya were alive now, he would have written about the incursions of Chinese troops into Indian Territory and the deaths of Indian soldiers today. Would he have attributed this to the Prime Minister’s ignorance, complacency, or cowardice, or to military weakness and ideological ambiguities instead?

In fact, as the quotes in this article show, Narendra Modi has taken the personalization of foreign policy much further than Jawaharlal Nehru ever did. While underlining the bonds between the people of China and the people of India, Nehru never spoke of Chairman Mao in the syrupy and sentimental terms that Modi has spoken of Xi Jinping. It is worth noting that, in response to our Prime Minister’s stream of eloquence in Wuhan in 2018, the Chinese President had laconically responded: “I’m very happy to meet PM Modi. Spring is a good time to meet.” Yes, indeed. Spring is a good time to meet an Indian politician in China, and summer an even better time to snatch some territory in India itself.

War

The clashes on the border in 1959 presaged a full-fledged war three years later. This is unlikely to happen now. That, however, may be meagre consolation. These rising tensions with our powerful and unpredictable neighbour have come at a particularly bad time in the history of the Republic. Our economy is in awful shape; growth has been sluggish for several years, and the pandemic will further inhibit a potential recovery. The ill-conceived Citizenship Amendment Act has made our social fabric even more fragile, while gratuitously offending a long-time ally, Bangladesh. Our relations with another and even older ally, Nepal, may be at an all-time low. And our long-time adversary, Pakistan, continues to foment mischief along the line of control.

Our capacity to tackle these problems, indeed even our ability to adequately understand these problems, is inhibited by the political culture of the day, where the government and the ruling party seek to present the Prime Minister as infallible, and his policies as beyond criticism. Nehru himself would never have remotely considered mocking someone like Deen Dayal Upadhyaya as anti-national. Yet those decorated army veterans who presciently warned of the Chinese incursion in Ladakh several weeks before the clashes in the Galwan Valley were savagely set upon by right-wing trolls and the Godi Media.

The tragic deaths of our soldiers must surely force a reset of our China policy. Given the mess the country is currently in, this reset should go beyond our relations with one country alone. Our economic policy, our social policy, our foreign policy, all need to be looked at afresh, and informed less by the personal instincts of the Prime Minister and more by hard realities on the ground.

(Ramachandra Guha is a historian based in Bengaluru. His books include ‘Environmentalism: A Global History’ and ‘Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World’.)