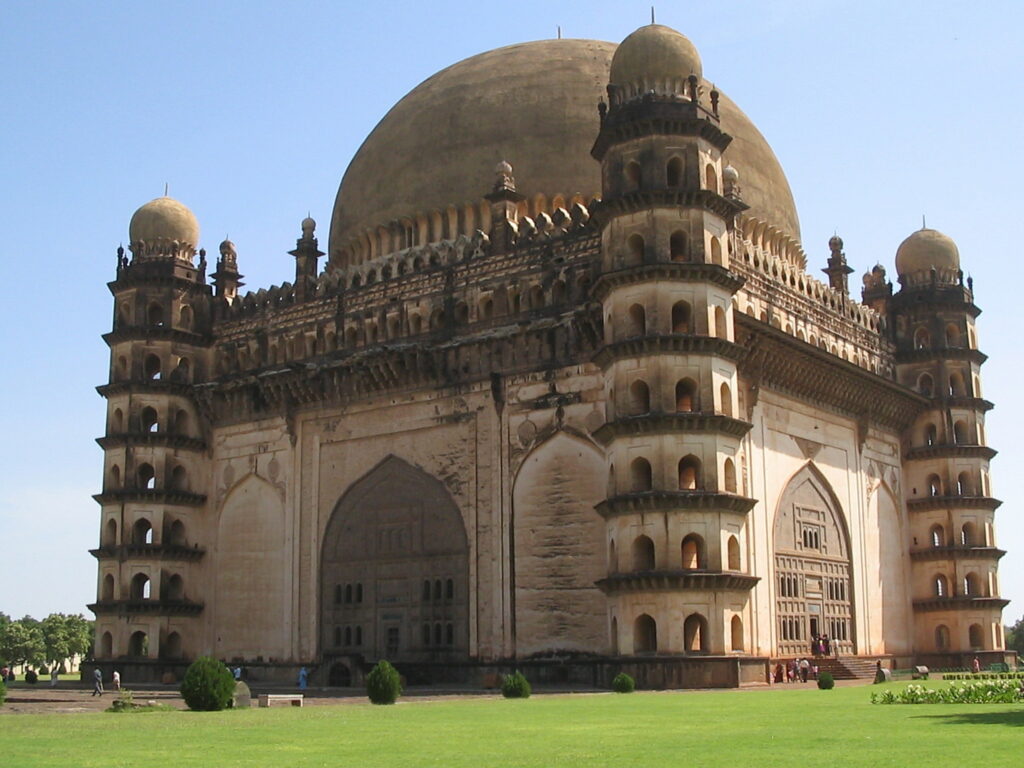

Death is serious business. In historical terminology, grave, crypt, tomb, mausoleum, memorial and necropolis are differently meaning words but are sometimes used interchangeably as their core function remains the same i.e., to keep alive public memory. Take the case of South Asia alone, there are aesthetically crafted, ostentatious tombs of various kings and queens and their close relatives spread out in the entire country. These grand tombs of the medieval Indian period of history which have come to be known as mausoleums serve as memorial monuments to convey forceful messages about the events or individuals they commemorate. To name a few: the Humayun’s tomb and Adham Khan’s tomb at Delhi, the tomb of Itimad-ud Daulah and the Taj Mahal at Agra, Akbar’s tomb at Sikandra, Sher Shah Suri’s tomb at Sasaram, Jahangir’s tomb at Lahore, the Bibi ka Maqbara at Aurangabad, the tombs of the Bahmani and Baridi sultans at Bidar and Ashtur, the Gol Gumbaz and the Ibrahim Rauza at Bijapur, the Qutb Shahi necropolis, the Asaf Jahi graves at the Mecca masjid and the Paigah tombs at Hyderabad, and the Gumbaz at Srirangapatnam, were constructed for a special purpose.

When kings, nobles, architects, masons and artisans came together to design and construct memorial monuments, apart from a lot of sweat and labour and expensive materials involved, choices were to be made about what aspects of a particular history were to be remembered and what parts could be left out. The issues that arise in this context concern history, public memory and the symbolism of public space and how public symbols are created to tell a narrative of a dominant period in history. When a community creates a memorial monument that is to remain for posterity, they are making a statement about how they want to be remembered, naturally implying wanting to be held in esteem. As a result, these structures influence the way succeeding generations should recollect about their ancestors. At the same time, the structures serve as relics of the past shedding light upon the beliefs of the people and the period when they were created. After all, these structures were meant to immortalize individuals and eras and celebrate death.

This leads us to a related and important issue of burial customs. Sometimes the deceased were entombed above the ground, rather than under the ground especially in the case of royalty and clergymen; sometimes the churches, dargahs or mausoleums constructed to provide a large space for the grave on display was not the actual or real grave itself which was found much below the ground level in the underground basement at the same site. Such subterranean chambers called crypts are commonly seen in Greco-Roman history, Egypt and the Vatican City and in different countries of Europe and South America from the early times. The same feature is also found in many of South Asia’s famous mausoleums. This is of great historical significance as the purpose to entomb a deceased above the ground with in-ground crypts was in sharp contrast to the custom of traditional burial.

Mausoleums are very often beautiful and elaborate works of architecture housing a grave which has been purpose-built to lay one or more important personalities to rest above ground level, instead of being buried in the earth. Primarily, the floor plan of a mausoleum was built on an elevated platform with ostentatious, beautiful architectural patterns of domes and arches and open corridors running right around. It also started to include more space for large gardens, water pools or fountains, smaller associated buildings like mosques, step wells, and baths. With this increased desire for richness, a complex design of a grand mausoleum came up. The accompanying paraphernalia which symbolize a grandiose royal scheme was meant to reinforce the close connection between power and ceremonial. Many kings of the past, even Heads of State today, mark their rites of passage with splendid ceremonial and spectacle. Such spectacles continue to be a prominent part of medieval and even modern political systems, but their precise meaning and importance often remain unclear in understanding royal rituals in traditional societies. While the simple grave quietly rested below a beautiful mammoth mausoleum fulfilling the spiritual dimension of ‘unto dust do we return’, the grandeur visible to the public eye catered to the worldly dimension.

These public mausoleums, also known as community mausoleums, entomb a prominent individual or more than one individual inside a single building structure. In a public mausoleum anyone is able to visit and pay their respects to the deceased. Well-known examples of public mausoleums in India with symbolic graves above the ground level and the true tombs housed in the crypt below are the Taj Mahal and Qutb Shahi Tombs. In these fancy models of tombs and internments, there are crypts within a mausoleum that is the part of the structure that holds the actual remains of the deceased. It forms the heart of the entire monument, its most sacred part mausoleum and the reason why it exists. The building itself is a memorial to the deceased. But it also provides protection for the crypt and the remains inside. The real tombs of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal at the Taj Mahal’s underground crypts or the tombs of Ibrahim Qutb Shah, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah and Abdullah Qutb Shah at the Qutb Shahi necropolis are specific examples of these.

Sometimes, private mausoleums meant exclusively for the family were constructed before a certain person’s death. Then, there were also garden mausoleums often beautifully decorated with plants, flowers, statues situated outdoors rather than indoors with provision of niches (for cremated remains) and casket interment. Lawn crypts and sarcophagus mausoleums were built in a style that was specifically underground rather than above-ground with no doors or windows as a part of its structure.

Thus, funerary architecture took varying forms and added new dimensions to imperial ambitions living longer than individuals thereby giving longevity to dynasties. Rituals play a vital role in political systems of all kinds. Considering the role played by royal insignia even in death is a matter of intrigue and understanding of imperial traditions which were supposed to continue through public memory. Debates over these questions often reflect the process of memorial monuments becoming battlegrounds of competing perceptions and different memories struggling to control the interpretation of history. Nevertheless, aristocracy and nostalgia are handsomely illustrated through these memorial monuments which are architectural masterpieces.

Salma Ahmed Farooqui is Professor at H.K.Sherwani Centre for Deccan Studies, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. She is also the Director, India Office of the Association for the Study of Persianate Societies (ASPS).