Rahul Gandhi being shoved around by UP police at the Yamuna Expressway, on Thursday, was arguably the most politically potent image of the Congress leader yet. With his sister Priyanka Gandhi and a large group of supporters in tow, Rahul was trying to reach Hathras to meet the family of a 19-year-old Dalit girl who was allegedly gang-raped by upper caste men and later succumbed to the injuries inflicted on her. Not too later, the pictures of the former Congress president with the victim’s family emerged. Then, he was seen leading a tractor rally to Haryana to protest against the three contentious farm bills.

Many hailed Rahul as the only leader in the opposition who consistently showed courage to raise the right issues, while others praised his audacity against a formidable political rival and imploring him to not give up the good fight.

We have been seeing a new avatar of Rahul Gandhi over the last couple of months. He has been actively intervening—in quite a measured, thoughtful manner—as an opposition leader in the middle of an unprecedented health crisis. He spoke extensively on COVID-19 measures, economy and on the issues of the migrants. His tone, much to everyone’s surprise, was constructive rather than confrontational—unlike the stand the Congress party took in 2019 parliamentary elections.

Watch his interview with Raghuram Rajan on YouTube.

A serious question now arises—did Rahul Gandhi finally arrive to deliver what has been expected of him throughout? Predictably, the Gandhi siblings are seizing the opportunity to criticize the ruling BJP for the Hathras horror, the contentious farm bills and others. But, what now?

The ‘Belchi’ analogy

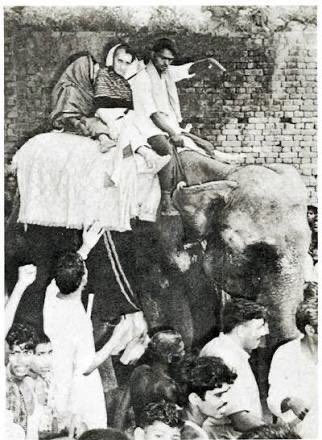

In August 1977, five months after the Congress was thrown out of power in the post-Emergency general elections, Indira Gandhi had decided to visit Belchi, a small hamlet in Bihar’s Patna district. Her visit had changed the course of Indian politics and also Indira’s political fortunes at a time when the horrors of the Emergency and the result of the Lok Sabha polls had many writing obituaries of the Congress’s electoral domination.

Trudging through sludge atop an elephant, Indira took a four-hour journey to reach Belchi where eight Dalits and three others from deprived communities had been killed by upper-caste landlords. Indira met the families of the victims of caste violence and, in the weeks and months that followed, capitalized on the publicity that her arduous trek generated to project herself as the saviour of the oppressed.

Though the times have changed, the Belchi imagery, a symbol of the Gandhi family’s appetite for political combativeness and fortitude, remains. However, Indira never slipped into inaction after her Belchi sojourn. Rahul on the other hand, touted as an absentee politician, could never turn several politically viable moments into his favor.

Rahul’s ‘Pappu’ brand and lack of power-hungriness

Rahul Gandhi was repeatedly mocked as “Pappu” by Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party during India’s 2014 general election, when the then incumbent Congress party secured just 44 of 545 parliament seats — the lowest tally in its history.

A dim-witted ‘Pappu’ is not what he is. “Most Indians have this knee-jerk reaction that he is an idiot,” said Gurcharan Das, writer and former chief executive of P&G India, in an interview. “I don’t think he is an idiot at all. He is bright and sensitive. But I don’t think he has the appetite. You have to be hungry. India deserves a leader who really wants to be that leader. I just don’t think he has the ability.”

In the book India Tomorrow: Conversations with the Next Generation of Political Leaders, Rahul was described to be ‘forthcoming, generous and frank’ too. “He has a good sense of issues faced by the citizenry and is conscious of what is said about him by his opponents.”

For all his frenetic campaigning, Rahul’s lack of any prior government role leaves him disadvantaged in a leadership contest with Modi, who is popularly seen as an experienced, decisive and hardworking strongman. Though Rahul Gandhi has improved as an orator over the past years, he is no match for Modi-Shah’s fiery rhetoric. “His general demeanour makes us wonder if he’s a ruthless enough for the cut-throat world of Indian politics,” the book states.

The Hathras incident, however, has given the privileged, dynastic scion another chance to redeem himself as a populist leader. But, to claim that he is finally arrived based on a day’s event is not right—he can be seen as a compassionate human, at most. His test lies in his backyard. How he confronts his privilege, addresses the leadership crisis in the party and shed the ‘Pappu’ image, to a large extent, will determine the future of Rahul Gandhi and the Congress Party.