Washington:A recent study has revealed some cells that are ‘born to be bad’ could be identified early, preventing the need for repeated endoscopies.

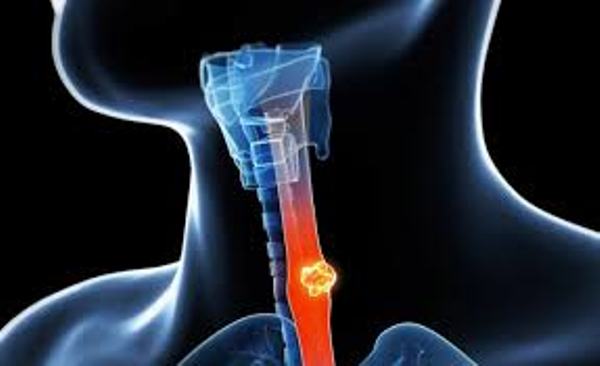

Barrett’s Oesophagus, a common condition that affects an estimated 1.5 million people in the UK alone involves normal cells in the oesophagus (food pipe) being replaced by an unusual cell type called Barrett’s Oesophagus, and is thought to be a consequence of chronic reflux (heartburn).

People with Barrett’s have an increased risk of developing oesophageal cancer. Although the overall lifetime risk of developing oesophageal cancer in people with Barrett’s is significant, most Barrett’s patients do not develop cancer in their lifetime.

While currently there is no easy way to distinguish between high and low-risk Barrett’s patients, regular surveillance by endoscopy is the best way to prevent cancer and know about it.

A test based on the genetic make-up of the Barrett’s lesions could benefit patients through improved diagnosis, giving people at high risk of cancer the best care, and reducing the burden of endoscopy for those at low risk.

Trevor Graham from QMUL’s Barts Cancer Institute said, “We have shown that some Barrett’s oesophagus lesions are ‘born to be bad’ – and conversely that some are ‘born to be benign’. Once these results are validated in other patients and over longer periods of time, we will be able to say with confidence which people with the benign form can be spared unnecessary endoscopy and worry.

This will dramatically improve the quality of life for people with Barrett’s, and provide substantial cost saving to healthcare providers.”

The team followed up more than 300 Barrett’s patients over three years, and analysed around 50,000 cells in the process. They performed genetic analysis of individual cells and measured the genetic diversity in each lesion to track it over time.

The results validated a previous group’s discovery that measurement of the genetic diversity between Barrett’s cells in any given lesion is a good predictor of which patients are at high risk of developing cancer.

In addition to it, the team found that there were no significant changes in genetic diversity during the three years that the patients were followed. This suggests that the genetic diversity amongst a person’s Barrett’s cells is essentially fixed over time, and mutations have little impact on the lesion’s development.

Whenever someone’s Barrett’s is tested, their future risk can be predicted regardless of how soon it is after the appearance of abnormal cells.

Graham commented, “Our findings are important because they imply that a person’s risk of developing oesophageal cancer is fixed over time. In other words, we can predict from the outset which Barrett’s patients fall into a high risk group of developing cancer – and that risk does not change thereafter.”

The study is published in Nature Communications. (ANI)