In this context, he quotes a letter by Allama Shibli Nomani:

‘Maghrib prayer? Praise be to Allah! What a magnificent sight this is! One’s heart starts bouncing with excitement [at this scene]. Syed Saheb [Sir Syed] too joins the prayers. Because he happens to be an Ahl-e-Hadith, he loudly pronounces “Ameen”. The echo of his “Ameen” increases, even more, the state of one’s religious zeal. I feel proud that I have played some part in creating this new life [in the college].’

Commenting on the last sentence of Shibli, the author opines:

‘Maulana Shibli has given the impression that the change in the students and their interest in religion is the result of his training. It is possible that Shibli had also taken part in giving this training to the students. But Shibli did not have much contact with the Department of Theology, and he only lectured on Qur’an attended by the students with keen interest. Students’ attendance in prayers in large numbers and their keen interest in religion resulted from Maulana Abdullah Ansari’s hard work.’

The very special status that Maulana Ansari enjoyed at Aligarh was that not only was he the first Dean but he was appointed in contrast to the standard procedure and through Sir Syed’s personal decision in which neither the members of the College nor the administration were entitled to interfere.

Would that the administration, teachers and the students of AMU had read the rare references and excerpts quoted by the author? But, alas, what to talk of the present generation decline had started in Sir Syed’s own time. Writes Noorul Hasan Rashidi:

‘But even during his own life there came such a turning point in this movement that it started losing focus and subsequently these objectives disappeared from sight.What to talk of the real aims and objectives even if a glimpse of these is shown to those who are associated with Aligarh [today], they would react with aghast and say: “Was it really so?”’

Countless writings by individuals and coteries with vested interest are replete with misquotations and distorted write-ups of Sir Syed. Rarely would such people refer to this message from him to the youths:

‘It is Islam that you have to live and die with, and you will have to protect it. What is it to us, if anyone among the children of our community rises as high as the shining stars in the sky but does not remain a Muslim? The only progress made while also establishing Islam is the real welfare of the community. We hope that you will always uphold Islam and will progress along with it. It will benefit you and bring prestige to the community, and future generations will benefit from it too.’

Except for the differences between Sir Syed and the Deobandi Ulema, their relationship was pretty cordial in the formative years of these two movements. As far as Sir Syed is concerned, he regarded the presence of Maulana Abdullah as a good omen and a blessing for the college. Sir Syed’s love and respect for Maulana Qasim Nanotvi is evident from his condolence note on him quoted by Dr Rahat Abrar in his essay in the book. Here are a few excerpts:

‘Time has mourned deaths of many and will lament on the deaths of many more in future, but to mourn the death of someone who seemingly leaves no successor to replace him is a matter of great sadness and pain. There was a time when among the ulema of Delhi, some were known and respected for their piety and knowledge. Equally, they had no match in their simplicity and humility. People thought that there would [perhaps] be no one like Maulvi Ishaq in quality after him. However, through his exemplary piety, virtuous values and simplicity, Maulvi Qasim has proved that Allah did produce another one with these qualities, perhaps, more superior than him as far as these qualities are concerned. Even those who disagreed with him on issues would admit that in this time and age, he had no match — he might not have been as deep in knowledge as compared to Shah Abdul Aziz, but in other aspects, he was superior to him. If he was not superior to Maulvi Ishaq in matters of humility, piety, and virtuousness, he was not inferior either. He had an angelic nature and angelic qualities. The departure of such a personality is very painful and tormenting for all those who survive him.’

After receiving the first report published by Darul Uloom Deoband, Sir Syed expressed his impressions thus:

‘Deoband is a small town. Although not a very famous city, by looking at the resolve, determination and pious thinking of its residents, one is forced to give it precedence over well-known cities… Hats off to them, that due to their concern, there has been tremendous progress in quantity and quality within a short period.’

Maulana Abdullah Ansari’s family tree goes back to one of the most prominent companions of the Prophet, Abu Ayyub Ansari. On this aspect, the book contains a detailed and interesting article by Tariq Ghazi Saheb.

An incident, narrated in the book, of the earlier days of the College that relates to the hard work by Maulana Abdullah Ansari and the atmosphere created by him would be of interest to the readers.

The king of Afghanistan Ameer Habeebullah Khan had come to visit the college. When he was taken to the Department of Theology, he refused to give any opinion without testing the boys. For this Maulana Abdullah selected and presented 50 students. The King picked up some of them and asked them to sit close to him. He then asked a student to recite any verse from the Holy Qur’an that he could remember. The student recited a part of Surah Ali ‘Imranin his beautiful voice in the Egyptian style. The recitation mesmerised the audience. Tears were flowing from the King’s eyes. As the boy finished recitation, the Ameer stood up and made a speech. At times he spoke in Urdu, Persian and English, and kept saying that whatever had been reported to him about the college was wrong.

Later he admitted that he had deliberately asked difficult questions on Islamic jurisprudence and said: ‘I have tested the students and satisfied myself. And now my answer is that everything is fine here, and I am very pleased.’

Reviewer’s gratitude to the author

As someone who does not only come from Deoband but studied at Aligarh as well, feeling indebted to the author is only natural. But now, a very personal reason has been added to this sense of indebtedness.

In my childhood, I had heard from my grandfather, Hafiz Abdul Jalil Khan, and other elders in the family that the grandfather of my grandfather Maulana Abdul Aziz Khan was in the first batch of graduates of Darul Uloom Deoband. They said that he had also taught at this great institution. Among the relatives in Deoband, it is common knowledge that Maulana Abdul Aziz Khan was a great scholar. According to my grandfather, Maulana Abdul Aziz Khan had a strong inclination towards Sufism and devoted much of his time to studying and worshipping. Family sources say that he had a vast personal library, but because no one could carry his academic legacy and look after his books, all of them were donated to Darul Uloom Deoband. His son and my great-grandfather, Abdul Hafeez Khan was more interested in local politics and little zamindari. He was also an elected member of the local municipal board.

We had heard these stories since our childhood. Still, when Maulana Abdul Aziz Khan’s name was not included in the list of either the students or the teachers published at the centenary celebrations of Darul Uloom Deoband, I, along with other youths of the family, started suspecting the authenticity of what we had been hearing about Maulana Abdul Aziz Khan because all of these were mere oral claims unsubstantiated by documentary evidence. Noorul Hazan Kandhalvi Saheb has indeed done a tremendous personal favour to me and to my family members by providing documentary proof of it.

After seeing Maulana Abdul Aziz’s name in the above-reviewed book, I thought to have a look at ‘Darul Uloom Deoband ki Jame wa Mukhtasar Tareekh’ (A Comprehensive and Brief History of Darul Uloom Deoband). Thankfully this too has his name on page 760.

Some excerpts from Marajul Behrain

‘Generally, it is written and said that the first batch of the graduates of Darul Uloom Deoband was the one that included Hazrat Maulana Ashraf Ali Saheb Thanvi. But despite being prevalent and often referred to in writings, this is not true. The fact is that the first batch of the graduates of Darul Uloom is the one that included Maulana Abdullah Ansari et al. It is they who have the credit of being the first graduates of Darul Uloom. Classmates of Maulana Ansari, who have been mentioned in the Roodad [minutes] include: Maulvi Mohammad Murad Pak Pattani, Maulvi Abdullah Khan, Maulvi Abdullah Sahib Anbaitvi and Maulana Abdul Aziz Khan about whom it is claimed that this was the very first batch of the graduates of Darul Uloom.

‘…After the foundation laying [of Darul Uloom] In Muharramul Haram, 1283H (May 1866) when the list of students, who had been awarded degrees was published in 1289H, 1872AD, it had the names of Maulvi Murad Saheb Pakpattani, Malvi Abdullah Khan Saheb Gawaliari, Maulvi Abdul Aziz Khan Saheb Deobandi and Maulvi Abdullah Ansari Ambatvi. The Madarsa [Darul Uloom] Deoband had declared them its first batch of graduates and were awarded degrees. By that time,Dastarbandi[ceremony of putting turbans on their heads] had not been introduced….’

‘The Madrassa [Darul Uloom Deoband] had established a good practice since the very beginning that the best answers on the [text] books included in the annual exams used to be included in the annual report of the madrassa. Following this principle, the questions asked in the exam and the answers given by the first batch of students were also published… It included the answers provided by … Maulana Abdul Aziz Khan Deobandi… These answers reflect the high calibre and deep study, deep thinking and the grasp of the students on the subjects…’

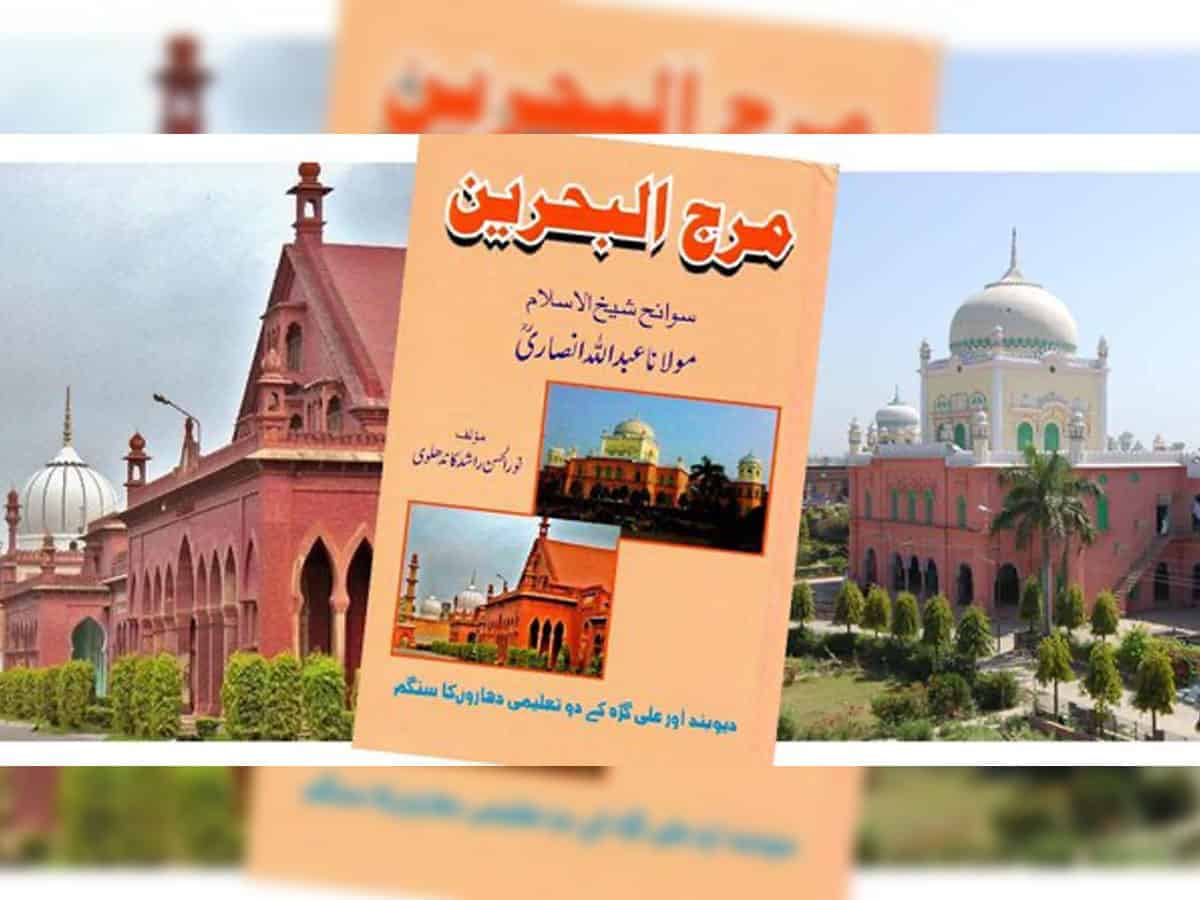

Marajul Behrain (Merger of Two Oceans)

Author: Noorul Hasan Rashid Kandhalvi

Pages: 256

Price: Rs 300

Publisher: Iqra Educational Foundation, A-2 Firdaus, 2 Veer Savarkar Road, Mahim (W) Mumbai 400016, India

Email: contact @iqraindia@org

M Ghazali Khan is a seasoned journalist and translator. He is interested in Middle Eastern and South Asian politics — especially Indian Muslims — history, media, culture and religion. Based in London, he has been running Urdu Media Monitor, a non-profit site.