Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s highly controversial historical drama “Padmaavat” was released a day before the unfortunate Kasganj incident when the country was celebrating Republic Day. A vicious narrative of nationalism in the small town in Uttar Pradesh resulted in a communal feud and led to the death of a young man.

I saw “Padmaavat” early last week and missed the first five minutes of the film which include a disclaimer that the film has nothing to do with historical correctness. Seated next to me in the theatre in Navi Mumbai was an elderly couple. The husband dressed in a kurta-pyjama, waistcoat, mojdi attire helped me understand the immediate implication of an allegedly historic film.

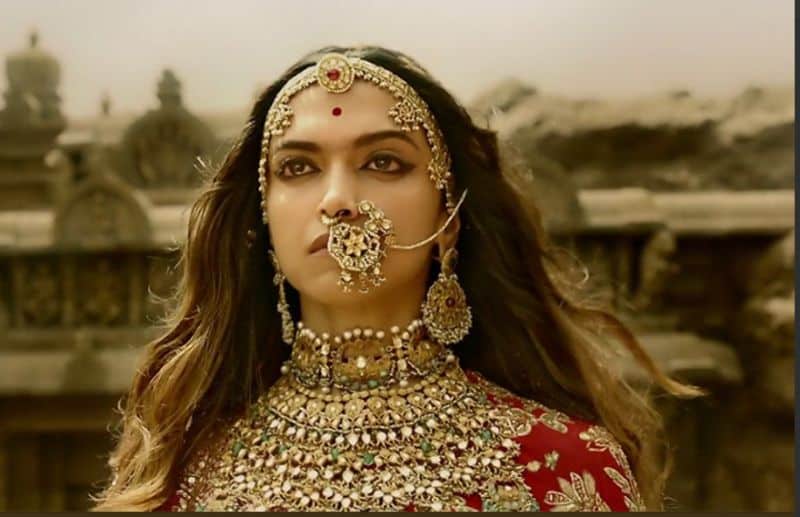

The film begins with Raza Murad as Jalaluddin Khilji with a flowing red beard, tearing into a big chunk of flesh, followed by his savage nephew, Alauddin Khilji, a kohl-eyed, debauched caricature of a Muslim prince. Alauddin has sex with a girl just before his nikaah with Mehrunnisa and treats his wife like a slave on their wedding night.

In the sequence right after, we are introduced to Raja Ratan Singh who is enamoured by the beauty and bravery of Padmavati, marries her without seeking the consent of his first wife, and introduces her as the maharani of the kingdom while his first wife fades away, thoroughly eclipsed by the glamour of the new queen. But Ratan Singh, being a Rajput, is allowed to enter your consciousness as the righteous, and Alauddin Khilji as the morally damned.

The moral corruption of Khilji continues with unsubtle references to his homosexual relationship with his slave Malik Kafur who pines for the attention of his king. If homosexuality is frowned upon in the Bhansali scheme of things, it is an attribute attached to Muslim rulers who by now are established as depraved, unscrupulous, two-faced opportunists. Each time Khilji backstabs or attacks a Rajput, you are not allowed to miss the symbolism. He does this while the green flag with the star and crescent is displayed boldly on the screen during the attacks on the sovereignty of the righteous nationalists. Present day Kasganj is pitching for a similar narrative.

Further on, just before Khilji kills his own nephew, his slave and confidant is seen reciting aayats from the Quran. Namaz can be heard in the background of Padmavati’s entry into Khilji’s kingdom where he plans to betray and conquer her. When Khilji deceives Ratan Singh and stabs him in the back, a pattern that runs through the film, the uncle sitting next to me tells his wife, “Aise hi toh hotey the ye sab mulla, hamesha peeche se maartey the sab Mughal log (Muslims have always been backstabbers)”.

The theme of a debauched Dilli sultanate runs through Bhansali’s narration of Mughal rulers. In his previous outing, “Bajirao Mastani”, the nizams and Dilli Darbaar are the bearded kohl-eyed brutes who attack the nationalist Peshwas to have absolute control over the country.

While “Padmaavat” bears no pretence of being a faithful account of events in history or even the fictional account of the poem it claims to be based on, it is disturbing to see Bhansali’s account of Amir Khusrau, the 14th-century mystic, historian and poet. Amir Khusrau is one of the pillars of Sufi Islam and Persian literature, also referred to as “Tuti-i-Hind” (Singing Bird of India). His poems and literary work which talk of the Brahmins of Somnath and Hajis at Mecca in the same breath are a metaphor to the secular idea of India. Yet Khusrau is reduced to being another court jester in “Padmaavat”, a yes-man to the savagery of Alauddin Khilji.

Bhansali has the cinematic liberty of giving a historical film a spin of its own. Mainstream and popular cinema cannot afford caveats to historical narratives. It is his democratic right to be able to express his point of view and it is our moral responsibility as a country to oppose the vandalism and terror unleashed by the hooligans of Karni Sena on him and the rest of the country. But here lies the irony. Bhansali published a page-long advert to pacify the Rajput community and convince them that the film was a paean to Rajput valor. He has been bending over backwards, requesting the Karni Sena to watch his film and give it a certificate of approval, going on to change the title of his film to ensure no sentiments are hurt. But does portrayal of Rajput valor demand vilification of another community?

In India, as in democracies around the globe, mainstream cinema has been a powerful tool that shapes public opinion and narrative. In a communally sensitive atmosphere in the country where lynchings and murders in the name of religion are becoming a norm, Bhansali has strengthened the stereotype of the evil, diabolic, murderous Muslim, a trope that forms the basis of right-wing hate of minorities. The calls for demolition of the Taj Mahal or disparaging comments about the iconic monument by leaders of the BJP has been an extension of this narrative that chooses to see the Taj Mahal as a Muslim monument built by the Mughals.

ranveer singh padmaavat 650

The theme of a debauched Dilli sultanate runs through the narration of Mughal rulers

Bhansali can indulge the exaggerated idea of Rajput bravado but should that necessitate vilifying a community that increasingly finds itself powerless in the present polarizing narrative? Beneath the grandiosity and stunning frames of “Padmaavat” lies a disturbing attempt at selling dangerous stereotypes that might yield immediate favors for Bhansali but leaves a disturbing impression of a community on a generation that seeks great inspiration from popular cinema.

Bhansali was awarded the Padma Shri in 2015. With greater fame and honour comes greater accountability, if not to the truth, then to the idea of a country whose founding principle was based on fairness and the absence of bias for the less privileged.

(Rana Ayyub is an award-winning investigative journalist and political writer.)

Courtesy: NDTV