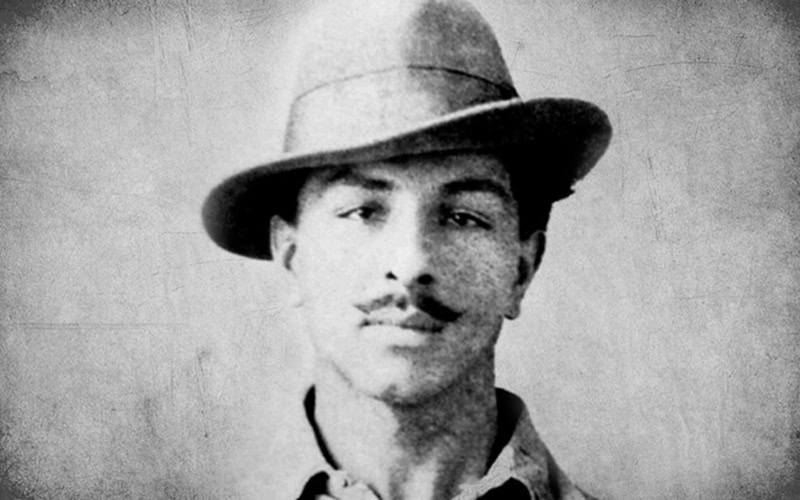

New Delhi: Punjabi folklore is full of the brave deeds of the two ‘Shaheeds’ of Bhagat Singh and Udham Singh, who have legendary status, and as a young child, Satvinder Singh Juss grew up listening to stories about them from his grandfather. Upon arrival in the UK at the age of nine, he recalls the annual commemoration of them held by the Indian Workers Association in town halls across the country for the future of a free India and the unfulfilled promise that they came to represent.

“I remained enthralled by the story of Bhagat Singh’s fight for freedom. Yet it was a story that was not known at all within the mainstream historical accounts of India’s path to freedom in the way that stories of Gandhi, Nehru, and Jinnah were,” Juss, a Professor of Law at King’s College London, a practising Barrister and a Deputy Judge of the Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) in the UK, told IANS in an interview about his book, “Execution of Bhagat Singh – Legal Heresies Of The Raj” (HarperCollins).

This, Juss said, “was despite the irony that even today, surveys have consistently shown that more than anyone else, it is Bhagat Singh who is the most popular figure in India. An even greater irony is how even today, in both India and Pakistan, it is Bhagat Singh who is seen as the principal figure in any rallying cry for a reformed politics.

“Whenever there is talk of embracing the modern values of diversity, pluralism and tolerance it is the name of Bhagat Singh that is on everyone’s lips. For all these reasons, it seemed to me that Bhagat Singh was a story whose time had come. It was a story that had to be told and re-told,” he added.

Growing up, Juss remained fascinated by the way in which Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru went to their death (in the Lahore Conspiracy Case) and the way that they smilingly kissed the hangman’s noose, and putting it around their necks themselves — all of this is told in the popular stories of Punjab.

“What remained unclear to me was the manner of their death. As a lawyer I remained fascinated by this. I was not the only one. There were those before me who remained frustrated in the knowledge that the main documentary repository of Bhagat Singh lay not in India but in Pakistan,” Juss explained.

The legal proceedings had taken place in Lahore, and Bhagat Singh’s family lived in Banga, which is in Lyallpur District in present-day Pakistan. When he read Kuldip Nayar’s book, “The Martyr”, written in 2000, he noticed his lament at how difficult it was for even him, (who had gone on to serve as Indian High Commissioner in London) to have access to previously unexplored material in Lahore.

“There were rumours that one reason for this inaccessibility lay in the fear of Pakistani authorities that this would raise the complex question of ‘the Sikh problem’. This rumour, as I myself later discovered, was without any foundation whatsoever,” Juss said.

The catalyst to his writing the book was newspaper article by Prof. Chaman Lal of Jawaharlal Nehru University. He referred to the existence 132 files which lay concealed in the Punjab Archives in Lahore, and it was felt that these would shed new light on the story of Bhagat Singh. He too had been unable to access these files.

“I resolved that I should try. In the event, I found not 135, but more than 160 files in the Lahore Archives,” Juss said.

It was quite a challenging task and the biggest was getting permission as a writer to get access to the Bhagat Singh archive. The noted travel writer, William Dalrymple, once remarked about the Punjab Civil Secretariat that “to get to its gate is a difficult task, leave alone accessing the archives”, given that it is the bureaucratic nerve-centre of the Punjab province.

“After various written applications, I was able to do so and was met with the utmost help and generosity of heart by the officials at the Lahore Punjab Secretariat where the papers on Bhagat Singh are kept in excellent condition, with a proper index,” Juss explained.

There was also the challenge of meeting people who were still connected to the story of Bhagat Singh. In the three-judge Special Tribunal which sentenced Bhagat Singh to death there was one Indian Judge named Justice Agha Haider. He was able to meet and interview his descendant, “a graceful lady, whom I traced living in blissful retirement in Gujranwala in Pakistan”, Juss said.

Agha Haider had objected to the lack of even-handedness in the Trial. For that he was removed from the Bench and replaced by a more compliant judge.

“Had he not been despatched, there would have been a split-verdict of 2 in favour of death by hanging and one against, and Bhagat Singh would have escaped the gallows. Only in the case of a Zulfikar Bhutto, was there a hanging on a split-verdict,” Juss explained.

(Interestingly, it was Kala Masih who pulled the rope in the case of Bhagat Singh, and it was his grandson, Tara Masih, who pulled the rope for Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.)

“The challenge before me was how to frame this argument and I have described the legal machinations as a process of ‘coercive colonial legalism’,” Juss said.

To this extent, the book is a wealth of information, containing dozens of documents not previously seen.

“In fact, there are over a 100 images of these documents. I refer to the full four-page ‘challenge to jurisdiction’ of the Tribunal on the very first day of its sitting on 5th May 1930, which states: ‘We believe that freedom is undeniable right of all people, that every man has the inalienable right of enjoying the fruits of his labour and that every nation is indisputably the master of its resources.’ The reference to ‘inalienable rights’ is directly drawn from the English common law, but used by Indian lawyers in Lahore,” Juss explained.

This challenge throws the gauntlet before colonial rule with words that “we believe all such governments, and particularly this British Government, thrust upon the helpless but unwilling Indian nation, to be no better than an organised gang of robbers and a pack of exploiters equipped with all the means of carnage and devastations,” Juss elaborated.

“Kuldip Nayar believed that not only was the Tribunal rigged but the Privy Council in London was rigged, and that one day secret telegrams would reveal that it was under instructions to reject Bhagat Singh’s appeal against the death sentence,” Juss said.

“Documents showing that the President of the Tribunal refused interviews of the accused with their relatives (thus making it difficult for the accused to prepare their defence) have been shown for this first time in this book. The removal of two of the three judges at the same time (one of whom was Agha Haider, who favoured the accused) ‘for reasons of ill-health’ within two weeks of the Tribunal convening, have been shown for the first time. Indeed, a document showing how at the trial of Udham Singh (who avenged the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre by shooting dead Michael O’Dwyer in 1940), taking inspiration from Bhagat Singh, justice was denied, is also revealed for the first time,” Juss said.

What next? What’s his next project?

“I am writing a second book on Bhagat Singh, this time focusing not on the Trial, but on Bhagat Singh’s life in revolution, and his wider relationship with violence, which was much more nuanced and sophisticated than is commonly thought. This is because Bhagat Singh’s view was that as revolutionaries, they were ‘lovers of humanity’, and whether they should resort to violence was ultimately dependent on the actions of their oppressors, because they themselves wanted peace,” Juss concluded.