New York: A team of US researchers has redefined the conditions that make a planet habitable by taking the star’s radiation and the planet’s rotation rate into account – a discovery that will help astronomers narrow down the search around life-sustaining planets.

The research team is the first to combine 3D climate modeling with atmospheric chemistry to explore the habitability of planets around M dwarf stars, which comprise about 70 per cent of the total galactic population.

Among its findings, the Northwestern team, in collaboration with researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder, NASA’s Virtual Planet Laboratory and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, discovered that only planets orbiting active stars — those that emit a lot of ultraviolet (UV) radiation — lose significant water to vaporization.

Planets around inactive, or quiet, stars are more likely to maintain life-sustaining liquid water.

The researchers also found that planets with thin ozone layers, which have otherwise habitable surface temperatures, receive dangerous levels of UV dosages, making them hazardous for complex surface life.

“It’s only in recent years that we have had the modeling tools and observational technology to address this question,” said Northwestern’s Howard Chen, the study’s first author.

“Still, there are a lot of stars and planets out there, which means there are a lot of targets,” added Daniel Horton, senior author of the study. “Our study can help limit the number of places we have to point our telescopes”.

The research was published in the Astrophysical Journal.

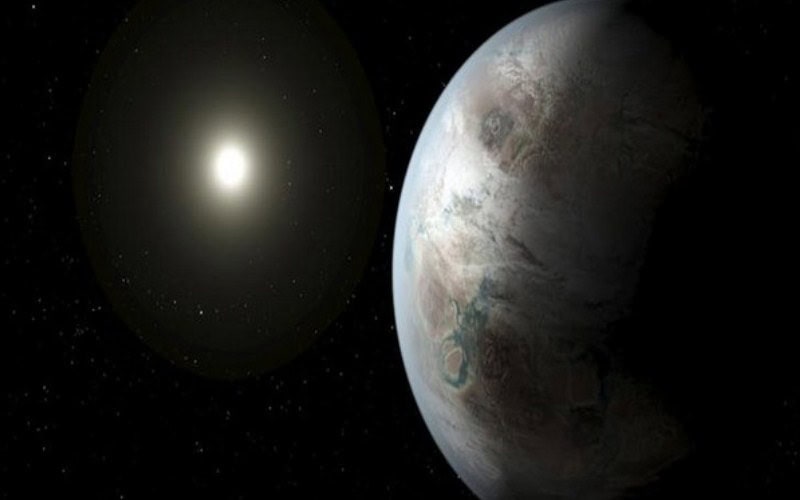

Horton and Chen are looking beyond our solar system to pinpoint the habitable zones within M dwarf stellar systems.

M dwarf planets have emerged as frontrunners in the search for habitable planets.

They get their name from the small, cool, dim stars around which they orbit, called M dwarfs or “red dwarfs”.

By coupling 3D climate modeling with photochemistry and atmospheric chemistry, Horton and Chen constructed a more complete picture of how a star’s UV radiation interacts with gases, including water vapor and ozone, in the planet’s atmosphere.

Instruments, such as the Hubble Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope, have the capability to detect water vapor and ozone on exoplanets. They just need to know where to look.

“‘Are we alone?’ is one of the biggest unanswered questions,” Chen said. “If we can predict which planets are most likely to host life, then we might get that much closer to answering it within our lifetimes.”