By Nasim Yousaf:

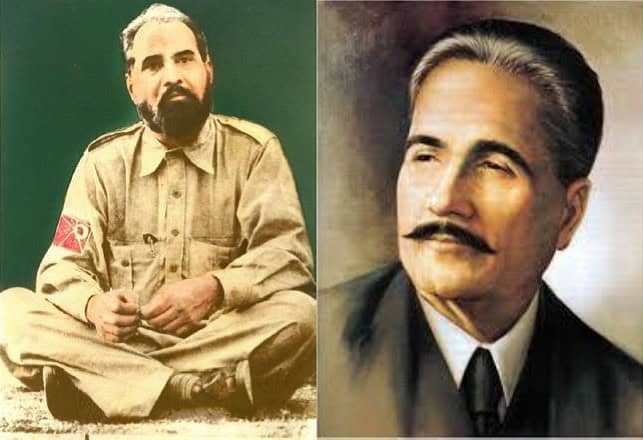

Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi and Allama Sir Mohammad Iqbal are regarded as legendary personalities of Asia. The two men have much in common; both graduated from the University of Cambridge and were illustrious thinkers, philosophers, writers, intellectuals, and politicians. They reached the highest pinnacles of fame and prominence in their respective fields. Both were also not without their controversies; this piece provides an introduction to these two men.

Mashriqi and Iqbal were both Punjabis whose ancestors were converts to Islam. Mashriqi was born in Amritsar in British India and died in Lahore, Pakistan, while Iqbal, a British India native, was born in Sialkot and died in Lahore. After high school, both men attended Christian educational institutions, Mashriqi went to Church Mission College (Amritsar) and Iqbal went to Scotch Mission College (later named Murray College) in Sialkot. Mashriqi also subsequently attended Foreman Christian College (F.C. College) in Lahore and Iqbal was admitted to Government College Lahore.

Mashriqi obtained his M.A. in Mathematics, while Iqbal obtained an MA in Philosophy. From 1907 to 1912, Mashriqi studied at the University of Cambridge and finished four Triposes in five years, breaking many previous academic records and stunning people in both the East and West. British newspapers showered him with praise – The Star, London, 1912 wrote: “It was hitherto considered not possible at Cambridge that a man could take honours in four Triposes in a short period of five years but it is credit to India that Inayatullah Khan of the Christ’s College has accomplished the feat.” In the 1920s, Mashriqi was inducted into several prestigious academic societies of Europe. Iqbal also graduated from Cambridge with a Bachelor of Arts; he later became a barrister-at-law from Lincoln’s Inn (England) and also obtained a PhD from a German University. The two men developed a strong command over multiple languages, including Arabic, English, Persian, and Urdu. During their lifetimes, both also taught at educational institutions and published poetry. They also competed for the prestigious Indian Education Service (IES) during their respective periods; Mashriqi was inducted into the said service, but Iqbal was denied.

Mashriqi and Iqbal both became well-known for their literary works. Mashriqi’s Tazkirah (a scientific look at the Holy Quran) was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature by learned men from the East and West (see Mashriqi’s biography in Al-Islah, Aug 30, 1935. p. 11). Iqbal’s Asrar-i-Khudi and Mashriqi’s Tazkirah were translated by the same well-known Cambridge University Professor, Reynold A. Nicholson. As Mashriqi and Iqbal gained prominence in British India, they were not spared from criticism. Many conservative religious leaders labeled them as kafirs (infidels) because of their progressive views on Islam. Despite their critics, both men continued to push forward on their agendas and emerged as top Muslim public figures in the Indian sub-continent and abroad.

It was clear that the two men had much in common. Mashriqi and his Khaksar Movement brought about a revolution in India, while Iqbal’s poetry inspired vitality and high spirits amongst the people. Both Mashriqi and Iqbal also seemed to agree that Islam was being widely misinterpreted. According to Dr. Shabbir Ahmed, in his publication Islam: The True History and False belief, “Various great minds have named this degenerate Islam variously…Allama Sir Muhammad Iqbal…termed it Ajami (Alien) Islam…Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi …called it Maulvi Ka Ghalat Mazhab (The Mullah’s Wrong Religion)…” Ultimately, both men inspired the masses in India as well as many others around the world.

Along with their many similarities, Mashriqi and Iqbal certainly had their fair share of differences. Mashriqi was not a follower of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and, like his father (Khan Ata Mohammad Khan), did not agree with Sir Syed’s way of promoting English education. Mashriqi felt that Sir Syed’s approach was spreading British influence in the country and destroying domestic traditions and culture, ultimately creating an inferiority complex among the people of the sub-continent. On the other hand, Iqbal was profoundly inspired by Sir Syed and his movement.

Mashriqi and Iqbal differed in their methods as well. Mashriqi believed that the key to freedom and regaining lost Muslim glory was through direct action, which he implemented using his Khaksar Movement. Meanwhile, Iqbal tried to revive Muslim glory through his poetry. Although Mashriqi wrote some poetry, he strongly felt that words alone would not be sufficient to achieve his goal of bringing about an end to British rule in India and instead would perpetuate inaction among the populace. Thus, Mashriqi built a private army of over 5 million Khaksars (along with countless supporters) to lead a massive independence movement. During his fight for freedom, Mashriqi remained under close watch by the British authorities and was arrested (or his movements were restricted) many times. Meanwhile, Iqbal emerged as a renowned poet. Additional scholarly studies are needed to examine their differing methods and the best path forward for the nation.

Perhaps the biggest difference between Mashriqi and Iqbal was their thoughts on a separate state for the Muslims. Mashriqi was opposed to partition, which he assessed to be primarily a British plan that was supported by only one Muslim party and some non-Muslim leaders. Mashriqi believed that the people of India could live together as a single, free and strong nation and that an independent judiciary and constitution were enough to protect the rights of Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and all other communities (Mashriqi published The Constitution of Free India, 1946 A.C., parts of which were incorporated into the Indian constitution after partition). Mashriqi also feared that partition would tear Muslims apart and result in the slaughter of innocent Muslims and non-Muslims and destroy peace in the region. Mashriqi felt that the arguments in favor of partition (namely that Muslims would be suppressed by the Hindu community in a united India and that Islam would be in danger [history of Muslim rule in united India and Muslim-Hindu co-existence for centuries negates both these arguments]) were merely ploys to scare Muslims and gain political support for a divided India. In contrast to Mashriqi, Iqbal (per many historians) supported the Two-Nation Theory and the creation of a separate homeland for the Muslims. He is considered the spiritual father of Pakistan.

Despite their differences, both Mashriqi and Iqbal maintained respect for one another. For example, while Mashriqi was Under Secretary of Education in the British Government, the Government used to seek Mashriqi’s recommendations on candidates for Knighthood, filling job vacancies, and other matters. During his tenure, Mashriqi recommended Iqbal (among others) for a vacancy in a Government position and also for Knighthood. According to Mashriqi’s book, Hareeme-Ghaib (page 296), “…several [people], for example, Dr. [Allama] Iqbal, Nawab Zulifiqar Ali Khan, Sardar Joginder Singh… received the title of Sir with his [Mashriqi’s] help.” Iqbal also held Mashriqi’s intellect and achievements in high regard. Iqbal used to discuss Mashriqi and his book Tazkirah at gatherings (at his house and in public) and in his correspondence with others (examples available at: www.iqbalcyberlibrary.net/txt/3540.txt). Poet Hafeez Jullandhri (who wrote Pakistan’s national anthem) disclosed in a speech, “One day I was sitting with Dr. Iqbal and some anti-Mashriqi people came with Tazkirah and asked Dr. Iqbal to write against it. Dr. Iqbal smiled and said, ‘Would I write against the Quran?’” Iqbal was inspired by Mashriqi and used some of Mashriqi’s thoughts in his poetry. On October 24, 1958, The Pakistan Times (Lahore) also reported on a photo of Allama Mashriqi, Quaid-i-Azam Jinnah, and Allama Iqbal together (the photo was published by the daily “Shahbaz” in British India). On a more personal note, Iqbal’s daughter, Munira Bano, also used to visit Mashriqi’s house in Icchra to play with Mashriqi’s daughter, Masuda Yousaf.

Following Mashriqi and Iqbal’s deaths, the mutual respect continued amongst their families. Both figures’ sons (late Engineer Hameedud Din Al-Mashriqi and late Justice Javed Iqbal respectively) and daughters-in-law (Dr. Sabhia Arshad and Justice Nasira Iqbal) met during different periods. Nasira Iqbal was also gracious enough to visit the Khaksar Tehrik Headquarters to condole the death of Hameedud Din Al-Mashriqi.

Allama Mashriqi and Allama Iqbal were two of the most prominent men in Asia’s history. Both were highly educated thinkers and provide a source of pride for all of Asia. Their lives mirrored each other’s in many ways and, despite their differences and critics, the two maintained a mutual respect for one another. Many books have already been written about these two men individually – and many more could be written comparing their lives and ideologies.

Mashriqi passed away in 1963 and Iqbal in 1938. Both men are buried in the historic city of Lahore, Mashriqi at the Khaksar Tehrik’s headquarters in Icchra (from where he started his Movement in 1930) and Iqbal in Hazuri Bagh.

For more information, see: “Allama Mashriqi and Allama Iqbal” (https://www.facebook.com/ AllamaMashriqi.AllamaIqbal)

Nasim Yousaf, a grandson of Allama Mashriqi, has been conducting research and writing books for nearly two decades. He brings a fresh perspective to the freedom movement, as his knowledge comes not only from historical archives, but also directly from his family and Khaksars, who had firsthand experience of India’s fight for freedom.

http://muslimmirror.com/eng/allama-mashriqi-allama-iqbal-pride-asia/