Ramachandra Guha

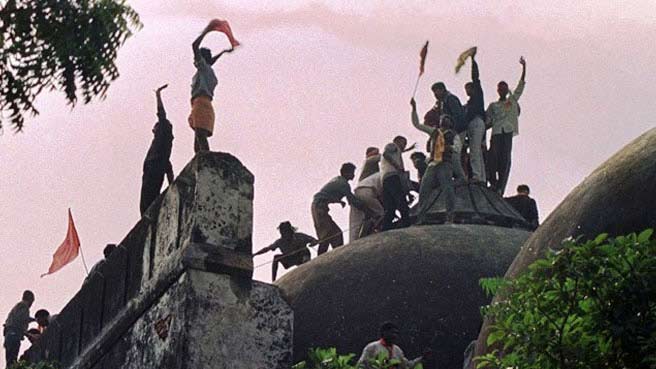

The Babri Masjid was demolished 25 years ago this week. Many Indians, this writer among them, viewed the demolition as an act of vandalism; whereas many others saw it as an act of vindication. The act, however, was divisive not merely in terms of perception. Preceding and following the demolition of the Babri Masjid were a series of riots, in which tens of thousands of innocent Indians lost their lives. No single event in independent India has so polarised public opinion; no single event has so adversely affected life on the ground, generating widespread suspicion and hostility between groups of citizens — and leading to much violence and suffering too.

Two politicians contributed significantly to the deepening of the Hindu-Muslim divide in the 1980s and beyond. The first was Rajiv Gandhi, who as prime minister, first appeased the Muslim fundamentalists by overturning the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Shah Bano case, and then appeased the Hindu fundamentalists by opening the locks of the small Ram shrine in Ayodhya. The second was LK Advani, who, as the leader of the BJP (then in opposition) conceived, organised and led the Rath Yatra which galvanised Hindutva sentiment across northern and western India. Thousands of young men flocked to Advani’s call, forming the bedrock of the army which sought to demolish the Masjid unsuccessfully in October 1990, before achieving ‘success’ two years later.

Advani’s march was not, of course, the first yatra undertaken by an Indian politician. Mahatma Gandhi himself had undertaken three major yatras; the salt march of 1930, aimed at undermining British colonial rule; the anti-untouchability tour of 1933-34, aimed at awakening Hindus to the iniquities of the caste system; and the peace marches of 1946-47, aimed at bringing Hindus and Muslims together. After Independence, lesser politicians have used the medium of the yatra to promote themselves. In 1983, the Janata Party leader Chandra Shekhar walked across the country, seeking to show that he cared more for the aam admi than the person who was then prime minister, Indira Gandhi. Before the last Karnataka assembly elections, Siddaramaiah undertook a padayatra to project himself as the alternative to the ruling BJP. Now, before the next state elections, with the BJP in opposition, BS Yeddyurappa is touring the districts of Karnataka in pursuit of his ambition to become chief minister once more.

However, of the many tours undertaken by politicians before and since Independence, Advani’s yatra of 1990 remains in a class of its own. Hindu-Muslim relations were already more fragile than they had been for many decades. In late 1989, Vishwa Hindu Parishad activists organised brick worship ceremonies for their proposed Ram temple, provoking riots in many places. In Bhagalpur, more than a thousand Indians, mostly Muslims, perished as a result.

I visited Bhagalpur in the wake of the 1989 riots, to see villages burnt, looms destroyed, and thousands of my fellow citizens, now without homes and livelihoods, living in refugee camps open to the sky. I do not know if LK Advani visited Bhagalpur himself. But he surely knew of what had happened there. And yet, a few months later, he led this provocative and divisive rath yatra. The symbols of Advani’s march, wrote one observer, were ‘religious, allusive, militant, masculine, and anti-Muslim’. The rath yatra provoked further rioting. The yatra was a major contributory factor to the horrific communal violence of the 1990s and beyond. As Khushwant Singh bluntly told Advani to his face, ‘you have sowed the seeds of communal disharmony in the country and we are paying the price for it’.

To be sure, the Republic had witnessed major riots both before and after L K Advani’s rath yatra. They included the anti-Sikh riots in Delhi in 1984, and the anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat in 2002. A great deal has been written of the complicity of the top political leadership in both. Rajiv Gandhi, as prime minister of India in 1984, and Narendra Modi, as chief minister of Gujarat in 2002, have both been criticised for , first, not doing enough to stop the rioting; and second, with using the riots to polarise majority voters in their favour, riding to electoral victory on the backs of dead bodies.

Both these criticisms are fair. Rajiv Gandhi, in 1984, and Narendra Modi, in 2002, could and should have done more to stem the rioting, and much more to provide succour and relief to those who suffered. However, neither Rajiv Gandhi, in 1984, nor Narendra Modi, in 2002, actually initiated the riots that occurred under their watch. By this token, LK Advani is far more culpable. For, with hate and violence already in the air, he set out to capitalise on it. To quote Khushwant Singh on Advani once more: ‘He, more than anyone else, sensed that Islamophobia was deeply ingrained in the minds of millions of Hindus; it needed a spark to set it ablaze’.

When faced with growing animosity between Hindus and Muslims, Mahatma Gandhi went on long walks and undertook long fasts to promote tolerance and harmony. On the other hand, when confronted with a similar situation, LK Advani seemed to have worked to intensify rather than contain religious conflict. And, as the recent attacks on minorities across northern India show, the politics that Advani promoted is still exacting its price. LK Advani has been,in my opinion, the most divisive politician in the history of independent India.

Ramachandra Guha’s books include Gandhi Before India

The views expressed are personal

Courtesy: Hindustan Times