During Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure in the late 1980s, the seeds were being sown for today’s political climate and its resulting artistic milieu. Two parallel forces were at work then. First was the gradual move towards liberalised markets that brought about consumerist lifestyles and a degree of economic opulence among certain subsets of Indians. Aditya Chopra’s and Karan Johar’s upper-middle class/NRI characters were the filmi embodiments this growing affluence.

Second, the Ram Janambhoomi gained more steam around this period.

Before these trends would reach their pinnacles with the sudden opening up of the economy in 1991 and the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition that unleashed Hindu-Muslim violence all over the country, three young thespians with the same surname burst onto the showbiz scene.

For those unfamiliar with the extraordinary world of Bombay cinema, this trinity comprises of Aamir Hussain Khan, Shah Rukh Khan (SRK), and Abdul Rashid Salim Salman Khan.

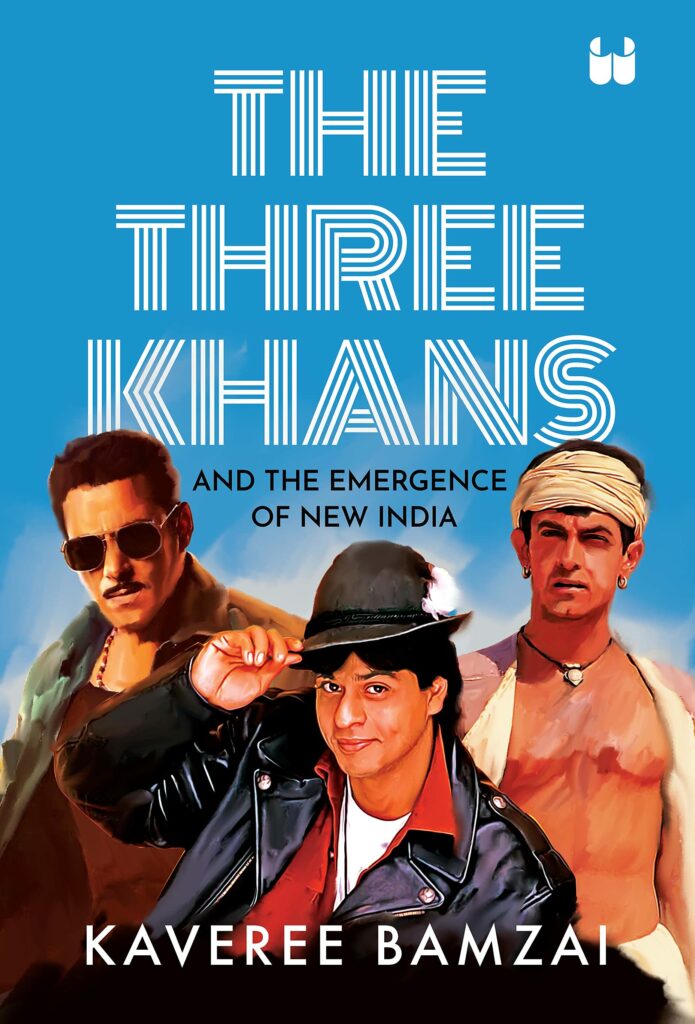

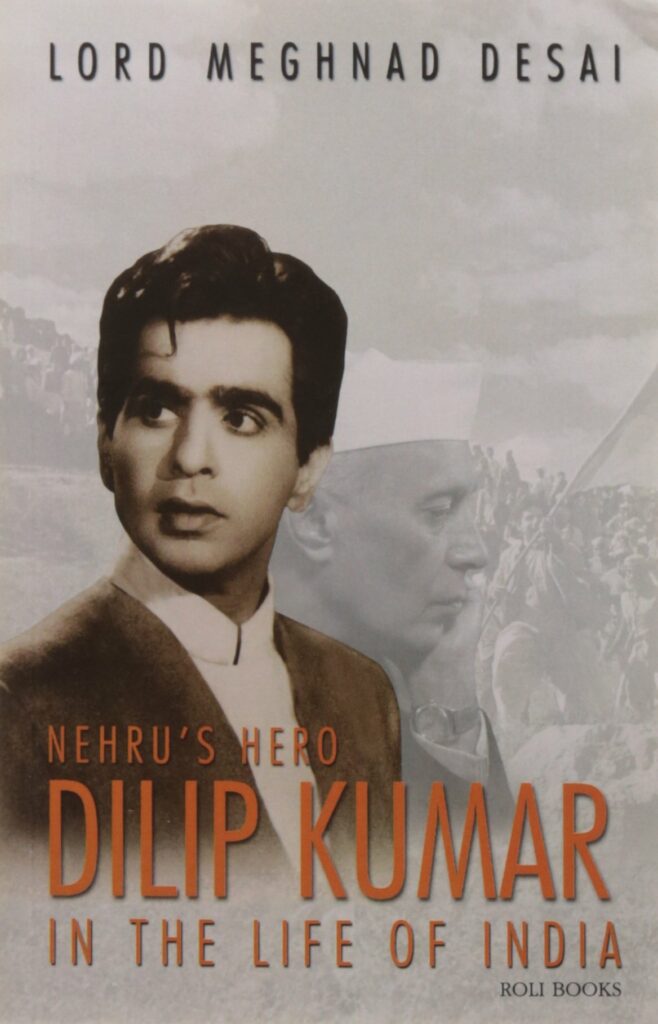

Kaveree Bamzai’s second book, The Three Khans: And the Emergence of New India, juxtaposes the troika’s journey with that of India’s from the late 1980s till the present-day where the current regime is becoming increasingly hostile towards the Khans’ co-religionists. The Lord Meghand Desai-authored gem, Nehru’s Hero: Dilip Kumar in the Life of India, showed how the Tragedy King’s career was as a cause, result, and representation of the post-1947 Nehruvian idea of a socialist, secular republic.

The former India Today editor also illustrates how the perfectionist’s, the NRI Hero’s, and Mr. Being Human’s paths have been intertwined with the winds of change engulfing the nation from the late 1980s till now.

These three actors – who happen to be Muslim and born in the same year – have had their storied careers enmeshed into the tapestry of a country. That too, one that is constantly weaving different fabrics of values, identities, ethics, and ideologies in and out of its makeup.

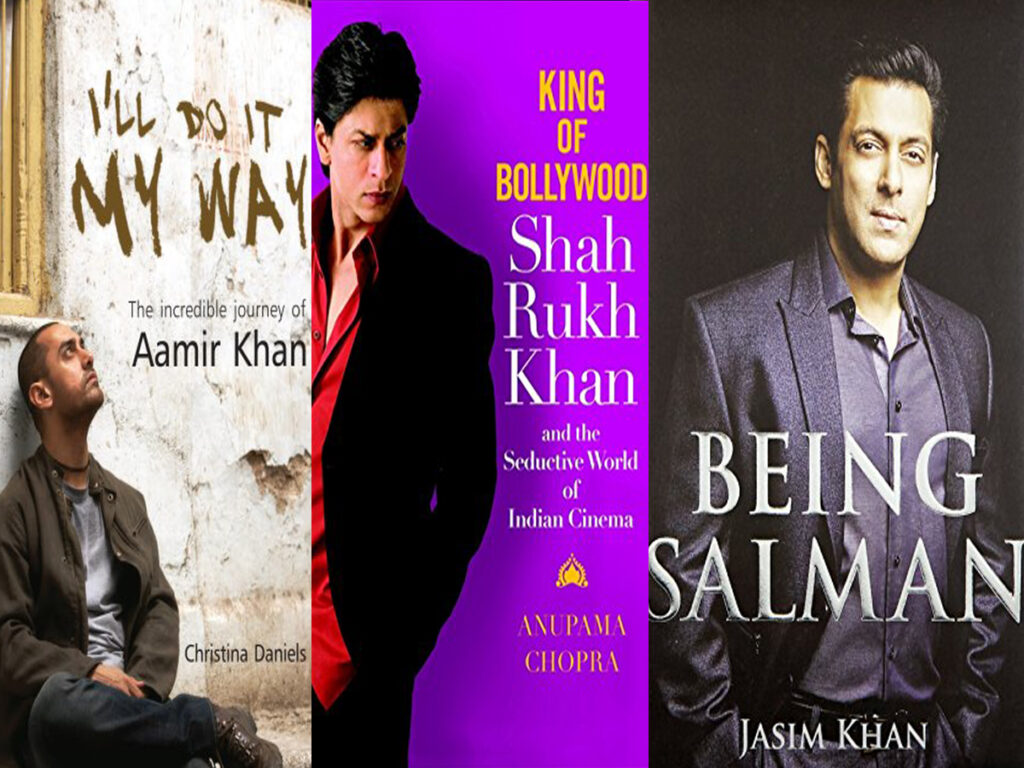

For biographical portraits that solely chronicle their personal as well as professional odysseys, one is better off reading Christina Daniels’ I’ll Do It My Way: The Incredible Journey of Aamir Khan, Anupama Chopra’s King of Bollywood: Shah Rukh Khan and the Seductive World of Indian Cinema, and Jasim Khan’s Being Salman.

But to deem The Three Khans as three biographies steeped in a socio-cultural evolutionary study of the film industry and India is to give this Westland Publications’ offering more of an academic character than it actually possesses.

Throughout the book, Bamzai keeps peeling away many layers off each of the stars’ personas — the consummate professional who keeps experimenting, the business savvy romantic heartthrob who resonates with Indians abroad, and the working class hero whose vehicular and verbal mishaps never went unnoticed. Interspersed with each Khan’s journey, along with that of India’s, are some forthcoming narrations of certain interactions between the Khans and those who helped shape their lives on/off celluloid.

When elaborating upon Aamir, the author recounts talking to his cousin and psychoanalyst Nuzhat Khan. “She told me he was fastidious about honesty and that he simply could not tell a lie. That, and the level of professionalism in his work, where each person was given due respect, was reflected in his personal life as well. He was not superhuman, she said. He did make mistakes and hurt himself. But he was totally open to learning and feeling new things, which she believed was an act of courage,” she quotes.

Within that paragraph is more unsavoury feedback from a former girlfriend who is quoted anonymously. “ ‘He is very literal. He has no grey areas,’ she told me, on the condition of anonymity. ‘It is his way or the highway. No ability to really connect and have dialogue outside his own received reality.’ “

Besides the infamous blackbuck poaching incident that occurred during the filming of Hum Saath Saath Hai (1999) in Jodhpur, an India Today article reported how Salman had complained that the lavish hotel room of the Umaid Bhawan Palace Hotel room was not to his liking. Co-stars Sonali Bendre, Tabu, and Neelam were also put up in similar types of rooms. Of course, Salman Bhai ended up getting his own suite. The piece also mentioned how amidst the same shooting schedule, he lost his shirt, roamed around bare-bodied throughout the hotel corridors, and also had partaken in target practice by shooting lined up soft drink bottles with guns.

However, when shooting for No Entry (2005), a different Salman surfaced. Bamzai writes that he immediately downgraded his accommodation at a South African hotel from a suite to a room after finding out that the rest of the cast stayed in normal rooms as well.

As for similar juicy details about SRK, there is a reference to an interview on Koffee with Karan where Gauri Khan basically described her husband as a possessive, controlling partner in their early days of courtship and how he stalked her when he came to Mumbai.

Three previously published biographies of Aamir Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan

The blending of such journalistic reportage, biographical and filmi trajectories, and a certain amount of academic flavor separates The Three Khans from the individual biographies pictured above.

The analyses of various learned scholars lend an authoritative, but not pretentious, sheen to this book. For instance, Bamzai quotes University College London sociologist Sanjay Srivastava on Salman Khan’s resonance with rural and small-town males with characters like Chulbul Pandey because migration from the villages to the cities has resulted in a certain romantic and nostalgic notion regarding the rural heartlands. The author also incorporates insights by American-Indian scholars who observed how Muslim characters were beginning to be shown as regressive, backward demons that didn’t want to experience the fruits of economic progress brought about by the 1991 liberalization. When not being depicted as outright reprobates out to endanger national security as well as law and order, Muslim movie characters found themselves boxed into the exotic caricatures of qawwals or Urdu-waxing poets.

To varying extents, the triumvirate hasn’t exactly steered clear of movies with such portrayals.

Switching swiftly between an academic and journalistic lens, the author never overwhelms the reader with scholarly information. Although disappointment awaits those who seek extended celebrity puff-pieces or tabloid character assassinations of the three piled into roughly 200 pages.

Though Bamzai also plays the clairvoyant as more concurrent, contradictory trends transpire. With the ruling dispensation injecting more doses of jingoism into mainstream cinema prior to the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, about a year later the coronavirus would somewhat level the playing field for overlooked talent. Overnight, the impenetrable fortresses of many industry oligarchs that are cinema halls were turned into abandoned structures. Whether it was Yash Raj Films’ hold on distributors or the Bachchan/Khan/Kapoor coterie member that had an easier path to stardom or the leeway to churn out a few more box office duds than an “outsider” before being written off, the colorful garden of Bollywood always its dynastic caretakers.

But lineage-lacking talent really blossomed in digital heavens with shows like Mirzapur, Delhi Crime, and Pataal Lok. These underdogs flourished further as Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney Hotsar, and etc. had the upper-hand with theaters becoming potential COVID-19 hotbeds. Jaideep Ahlawat and Pankaj Tripathi, whose prowess only got noticed in more recent times, always flew under the radar. Both Tripathi and Ahlawat didn’t even play second fiddle to Shah Rukh Khan in Dilwale (2015) and Raees (2017) respectively.

The pandemic has seen the rise of talent that for that most part flew under the radar, like Pankaj Tripathi (left) and Jaideep Ahlawat (right)

Films like Raees (2017) and Tubelight (2017) did punch below their weight with respect to box office numbers. Yet, they were the rare instances when Salman and Shah Rukh were more so actors instead of larger-than-life stars. Today a more discerning, egalitarian audience is doing its bit to ensure that acting abilities, plot, and trumps bloodlines and swashbuckling self-projection. Aptly, Bamzai surmises that Aamir is best positioned to hold his own with this new breed of movie-buffs.

Of course, boisterous nationalism, both in and outside the cinema hall, has its takers too.

Hence, today’s more virulent communal climate has also brought the three Khans into the crosshairs of the powers that be. The latest salvo in this campaign against this triad is the alleged drug use by SRK’s son, Aryan.

Regardless of what these various phenomena portend for the Khan trio, it is has been quite the ride for the film industry’s modern-day Dev Anand, Dilip Kumar, and Shammi Kapoor. The prospect of a movie with the three seems like a pipe dream, but The Three Khans: And the Emergence of New India is the closest we will get to seeing them featured side by side as main characters.